By Molly Meng-Hua Sung, guest contributor

This past year, the long-awaited Fundamental Science Review (commonly referred to as the Naylor Report) was submitted to Canada’s Minister of Science, the Honourable Kirsty Duncan. It confirmed something scientists have been saying for years: funding is tight. Furthermore, the strain of poor funding is borne largely by young researchers.

The consequence of weak research funding extends far beyond the lab. Investment in innovation has implications for many aspects of Canadian life, strengthening the economy, creating jobs, and positioning us to deal effectively with economic, environmental and social challenges.

But how do we, as Canadians, convince government that research is a priority? Can science advocacy make an impact and reverse the decade-long course of insufficient research funding.

The Naylor Report

The review, commissioned by the minister, evaluates the state of fundamental research in Canada. It diagnoses the shortfalls in Canadian research. Among the most pressing issues that the report identifies are:

- Federal spending (relative to GDP) on R&D has declined over the last decade, making Canada an anomaly amongst G8 and OECD countries.

- Spending is disproportionately directed towards priority-driven research, leaving fundamental research (discovery-motivated science) behind.

- Young scientists are not supported financially. Graduate students and post-doctorate researchers are increasingly forced to compete for limited research grants.

- The Canada Research Chairs (CRC) program is not functioning optimally.

The Naylor Report also presents recommendations to address these issues and to strengthen Canadian science. Notable recommendations include immediately re-investing in fundamental research and graduate/post-doctoral grants through budgetary increases, restoring funding to and restructuring the CRC program in favour of emerging professors, and creating a National Advisory Council on Research and Innovation to provide advice to the Prime Minister’s Office and Cabinet regarding federal spending on research.

Although Duncan appears prepared to address many of the organizational recommendations – particularly those addressing diversity and equity – she appears to approach some recommendations with more reservation. Notably, Duncan has not committed to any of the report’s recommended budgetary increases – despite acknowledging a need for more investment exists.

In addition, the 2017/2018 Federal Budget contained no new investments in the three federal research funding agencies, the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR), the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC), and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC).

Although the 2016/2017 budget provided a $95-million increase for researchers, this one-time increase is not enough to help Canada catch up to other G8 and OECD countries.

Lack of funding affects young researchers

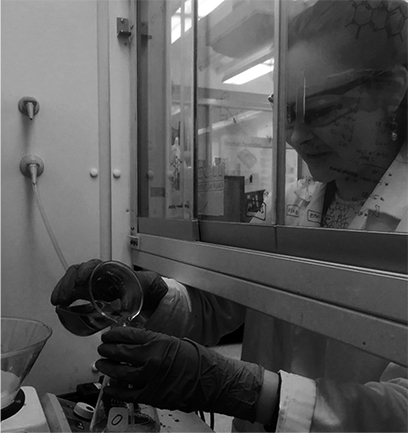

Graduate students across the country rely on federal grants to fund their research projects. Photo courtesy of Molly Sung

The Naylor Report is clear that young researchers shoulder the burden of lagging investment in fundamental research. The Global Young Academy (GYA) recently released a separate review on fundamental research to complement the Naylor Report. The GYA review presented data from an online survey of Canadian researchers (n= >13000) with 88 per cent of respondents saying that funding from industry partners is currently required to operate their research programs; this may add external pressure on the direction of their research. Additionally, 56 per cent of respondents believe that funding cuts will lead to fewer young Canadians pursuing research careers.

In fact, recent restructuring of CIHR (with no appropriate funding injection) has been described by a senior researcher as “eating our young” and current funding and evaluation structures by the three funding agencies operate at a “detriment to younger researchers”

It should also be acknowledged that the pursuit of knowledge through basic research can not only inspire the next generation of scientists but yield transformational applications in fields such as transportation, the economy, climate change, and medicine.

Science advocacy and agency: R&D finds its voice

Despite students being most affected by the last decade of inadequate research funding, until recently, efforts to directly engage and consult graduate students and post-doctoral researchers have been limited.

It is, therefore, no surprise that young researchers have taken matters into their own hands and are mobilizing to make sure researchers are heard. Many grassroots initiatives have been launched in the last few months to demonstrate to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and his Cabinet the importance of fundamental research and science funding. Such campaigns include the #SummerofScienceCAN Campaign led by the Association of Canadian Early Career Health Researchers, an open letter to Prime Minister Trudeau and Cabinet ministers Morneau, Duncan, and Bains by the student group Science & Policy Exchange, the #NextGenCanScience twitter campaign by the Canadian Society for Molecular Biosciences, and a letter-writing campaign by Evidence for Democracy.

Precedents

There is historical precedent for scientists and students successfully applying pressure on governments to make positive change.

In 1997, the U.S. Senate unanimously voted to double the budget for the National Institutes of Health (NIH) between 1998 and 2003 as a result of coordinated efforts by scientists, advocates, and lobbyists – in fact, many attribute the success of the campaign to testimonials provided by researchers. For his role in successfully lobbying for the increased funding, Dr. David D. Ho, of the Aaron Diamond AIDS Research Centre, was recognized as Time magazine’s 1996 Man of the Year. In 2001, President George W. Bush’s administration honoured the planned budget increase despite pressure to redirect new spending towards National Defense in the wake of the 9/11 attacks.

More recently, U.S. President Donald Trump’s administration proposed a 22 per cent budget cut to the NIH, sparking outrage from researchers and physicians. Through protests and public outreach campaigns, advocates gained enough public support to see a House of Representatives committee table a revised spending bill that actually proposed a 3.2% increase to the NIH’s budget.

In April 2017, scientists around the world marched in solidarity with U.S. scientists. Both photos, courtesy of Vanessa Sung

One historic Canadian example of how advocacy influences science funding is John S. Plaskett’s successful bid to the governments of then-prime ministers Sir Wilfrid Laurier and Sir Robert Borden in the early 20th Century to fund construction of the Dominion Astrophysical Observatory in Victoria, BC. Plaskett realized that existing telescope facilities in Canada would be insufficient to propel Canada to the cutting edge of astrophysical research and lobbied the federal government for three years before funds were finally granted for the new observatory in 1913.

A more recent Canadian example is the mobilization of scientists in the years leading up to the 2015 federal election. In 2012, scientists marched on Parliament Hill to protest the “Death of Evidence” in policy-making. Led by biology PhD student Katie Gibbs, the protestors gave mock eulogies lamenting cuts to research and changes to environmental laws.

After the march, Gibbs founded the science advocacy group, Evidence for Democracy. The group continues to advocate for evidence-based decision-making in public policy and helped bring science issues into the public debate for the 2015 federal election. The mobilization of scientists resulted not only in a government more willing to prioritize science, but a new collective bargaining agreement between the federal government and the union that represents federal scientists that includes commitments to protect scientific integrity.

These commitments will help to safeguard federal research from external biases and pressure from politics and industries, as well as prevent the muzzling of government scientists in Canada again.

Scientists marched on Parliament Hill to protest the loss of evidence in federal politics in 2012. Photo courtesy of Richard Webster, Death of Evidence

Successful student activism also has precedent. It was only five years ago that students in Quebec took to the streets to protest a planned 75 per cent increase in tuition fees and captured national attention. Tens of thousands of students participated in the public demonstrations and applied enough pressure on then-Premier Jean Charest’s government to shelve the proposed tuition hike.

But students have been active on the science policy front, too. To fill the absence of student voices in science policy, a group of graduate students in Montreal started Science & Policy Exchange (SPE) in 2010. They aim to bridge the gap between academia, industry, and government, and to ensure student voices are heard. They convened a group of STEM students to analyze the current state of education in Canada and highlight challenges facing STEM graduates. They published a white paper discussing their findings in 2016. The group gained the attention of Sir Peter Gluckman, New Zealand’s Chief Science Advisor, who brought the model home to encourage discussions around scientifically informed public policy.

Strength in numbers; unified messaging

While it’s unlikely that a science protest will reach the same levels of intensity as the 2012 Quebec student protests, we can learn one lesson from the student movement: there is strength in numbers behind a unified message.

If researchers don’t see money invested in fundamental research soon and Canada does not regain the ground it has lost in recent years in research and innovation compared to other G8 and OECD countries, Canada risks falling further behind in science. With a major funding gap in fundamental science and $459 million in unrealized research excellence, we have already put strain on young researchers and, without immediate action, we risk losing more talent to other countries readier to support research and innovation.

With the federal government considering funding allocations for the 2018/2019 budget this fall, it is imperative that the importance of fundamental research is conveyed not just to our politicians, but to all Canadians. All Canadians must come to understand that a healthy research environment is a strong economic investment and that, by funding research and leading innovation, Canadians can be the ones producing technology, not just buying it.

Researchers have the potential to propel Canada to the forefront of innovation in everything from space exploration to climate action. However, they cannot do that without funding.

–30–

This is the second article in a two-part series on the Naylor Report published by Science Borealis. Read the first article here >

edits to this article:

The Minister likely received the report months before June, as was noted in the original version of this article.

Science, Technology and Innovation Canada has reported on science funding in Canada since 2008.

Another initiative in which early career researchers lobbied the government is the Young Researchers Open Letter to Trudeau, about strengthening the environmental review process by basing it on evidence. https://www.youngresearchersopenletter.org/