Liz Martin-Silverstone and Raymond Nakamura, Multimedia co-editors

After our Science Borealis Reader Survey, we randomly selected four participating blogs to be profiled here on the Borealis Blog during 2016. This is the second of those featured posts.

RN: I’m delighted to introduce my new Multimedia co-editor, Liz Martin-Silverstone, a paleontological powerhouse studying across the pond.

LMS: Thanks for the introduction, Raymond! I’m so happy to be part of the Multimedia team.

RN: This post is a little bit different from usual, because we are featuring the work of one person, Laura Ulrich, the creator of the blog Monsters and Molecules. Although her blog was picked at random, we have been appreciating her work for some time. Give it up for Laura –

LU: (Bows to thunderous applause.)

LMS: I’m particularly excited about this since scientific illustration is something I love, despite being utterly un-artistic myself. Laura, what do you see as the relationship between visual arts and science education?

LU: I see them as vital parts of one another. When learning to draw, it is common to draw still lifes, to practice studying a specimen closely and to train your hands to accurately depict what you see. In science, to truly understand something you must observe it, and attempting to draw it helps tremendously. I am a strong supporter of the movement from STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math) to STEAM (the “A” is for Art and Design). Three of my greatest influencers are Leonardo da Vinci, Maria Sibylla Merian, and Frank Netter. Da Vinci was an incredible inventor and naturalist; Merian was a naturalist who is famous for her work on butterflies; [and] Netter was a surgeon whose medical illustrations are used to educate new practitioners of medicine around the world. I myself have his anatomy colouring book and it’s absolutely stunning!

RN: I have always admired Leonardo da Vinci, partly because he was a lefty like myself. Now it seems that after some serious deliberation, you’ve decided to pursue a teaching degree rather than train specifically in scientific illustration. How has the education program affected your thoughts about scientific illustration?

LU: It has fostered my belief that STEAM is vital. British Columbia is currently undergoing an education reform, with the new curriculum design encouraging more inquiry and project-based learning. I will never be the hard-facts scientist; my shelves are full of books like Arthur Spiderwick’s Field Guide to the Fantastical World Around You, The Resurrectionist, and A Natural History of Dragons. I hope that over the years, I develop a reputation as a teacher who blurs the lines between different curricula and subjects. I want my students to know they can expect more than memorization and follow-the-recipe experiments from my class. A buzzword in education is “artifacts”, something physical your students can take away from your class. I would love to try some sort of portfolio project with senior students, of which scientific illustration is a part. However, even something as simple as worksheets and colouring pages can be helpful. I have been repeatedly encouraged to start uploading to sites like Teachers Pay Teachers. I always thought my scientific illustrations were for educational purposes, but now I am on the frontlines and seeing where the demand is.

LMS: I had never heard of STEAM vs. STEM before, but I think it’s a great idea to cultivate that link between science and art, since so much of scientific communication is related to illustration, art and visual aspects. What do you think are the advantages of scientific illustration over traditional scientific communication methods?

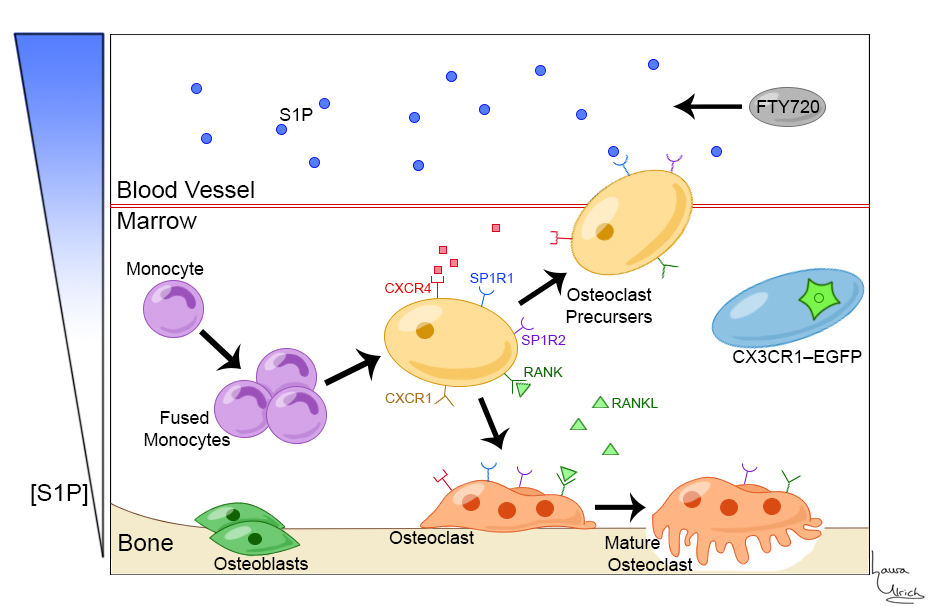

LU: Art transcends language. While many scientific papers are written in English, a Canadian scientist may be unable to read and respond to a paper written in German… I am a very visual learner. One paper I had to read and present on during my undergrad was…too dense! I struggled to comprehend what was happening until I sat down with my presentation partners and we talked through it, with me doodling how I thought it worked. In the end, we decided to have me turn the doodles into a full-blown diagram. Interestingly, according to my site stats, most of the views for that particular diagram come from Korea.

RN: I noticed when I studied in Japan that graphs and illustrations really helped me understand what was going on because Japanese was not my first language. As for actually drawing, do you have any tips, particularly for drawing in the field?

LU: For me, field drawings are all about building up a collection of resources for more refined works later… Leave your ego behind. Most field drawings are about speed and accuracy, not beauty… Focus on scale and general shape first, then hone in on the details. It is a good idea to have a ruler or some other measuring device, as records of size can help with refining sketches later… Make notes! Jotting down a behaviour or describing a texture can be a great resource later… And finally, bring a camera! I like to take pictures of everything I plan to draw, usually with something for scale in the shot as well. This gives you an invaluable reference for colour, shape, size, etc. If it is a complex 3-D object (such as a skull), I also recommend filming it from multiple angles to better see how the parts relate to the whole. They also can be very helpful for capturing several images of moving specimens to use as reference later.

LMS: That’s great. I’ll have to give that a go when I’m looking at fossils in the field! You use a combination of colour and black and white sketch work. What do you prefer and why do you use different methods?

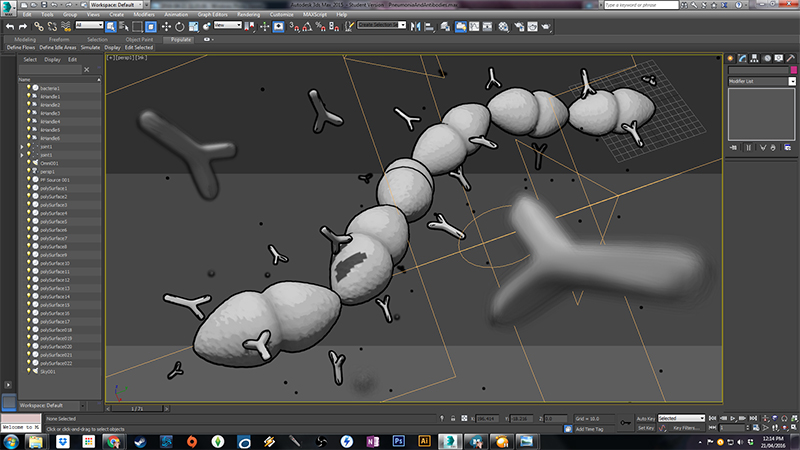

LU: Variety, mostly. I confess that I will never master any one thing because I never stick with it long enough. However, I do put some thought into the purpose of my work, and that dictates my method a great deal. Is it an anatomical diagram, something that may be printed out? Clean black lines will suffice. Is it an eye-catching piece, something meant for display? Colour most certainly. A year ago a tenured professor was looking for an artist to make some animal silhouettes for a paper. I was forwarded the email from so many professors and TA’s it was overwhelming, the sheer amount of support and the fact that these people remembered me! Of course I responded to the professor, including a couple select images and a link to my blog.

Over a week later, I finally heard back from him. He wrote “Unfortunately, your style is not what we’re looking for.” To me, style is a very fluid thing. Some days I wonder if I should have gone underground and become a Master Forger. In my frustration, and to fulfill another opportunity that then revealed itself, I made my Darwin portrait, which is composed of over 90 organismal silhouettes.

RN: I love how that portrait combines your attention to detail and conceptual ability to create a portrait that has layers of meaning. How would you summarize your take on science communication?

LU: I have always wanted to make science approachable, to take it off its pedestal and put it on the play table.

LMS: Thanks so much for speaking with us, Laura. Best wishes with your education program and the future!

If you like Laura’s art, make sure you check out her blog, Monsters and Molecules, for many more images.

*Images by Laura Ulrich, used with permission

One thought on “Science Borealis featured blog: Laura Ulrich – Monsters and Molecules”

Comments are closed.