Sonya Neilson, Physics & Astronomy co-editor

A few snowflakes drifted slowly to the ground as we pulled up to the MacKenzie Recreation Centre, a two-hour drive north of Prince George, BC. Having flown up the previous night from rainy Vancouver, our bodies were not used to the cold and we unloaded our van as quickly as possible. Along with the samples of astronaut food, craft supplies, and boxes of Timbits (a rare treat for many people in MacKenzie), we pulled out the Starlab: a portable planetarium flown in from the H.R. MacMillan Space Centre in Vancouver. Three other interpreters and I had travelled with these props to provide an astronomy open house night for MacKenzie’s approximately 4,000 residents.

When it comes to astronomy education in small communities like MacKenzie, one of the main challenges is a lack of resources. There just isn’t a large enough population to justify a telescope club, let alone a permanent planetarium. Canada has only 11 permanent planetariums; the nearest one to MacKenzie is a nine-hour drive away in Edmonton. What people in MacKenzie do have are great views of the stars. The isolation of the community means that it is almost completely free of light pollution, and the northern latitude means winter nights are long and dark. Students in remote locations have grown up with views of the stars, but with little access to related educational resources.

MacKenzie is far from unique. In 2006, nearly 20% of Canadians were living in communities of less than 10,000 people, many of which are relatively isolated. Travel within Canada isn’t cheap. Trish Pattison, a programmer at the H.R. MacMillan Space Centre, jokes that visiting the Eiffel Tower from Vancouver would cost less than a trip to MacKenzie. She is probably right. But is bringing a planetarium and interpreters up from Vancouver the most effective solution?

When we visit from Vancouver, we arrive with a big city mentality that can often be insensitive to local culture. For example, many of Canada’s small towns are dominated by First Nations peoples, so a different approach is required. Wilfred Buck, from the Opaskwayak Cree Nation, works as Science Facilitator at the Manitoba First Nations Education Resource Centre (MFNERC) and runs the Ininew Achakosuk (Cree Stars) program. He brings a portable planetarium similar to our Starlab to Manitoba’s First Nations Schools, sharing the study of astronomy from the perspective of Canada’s First Nations.

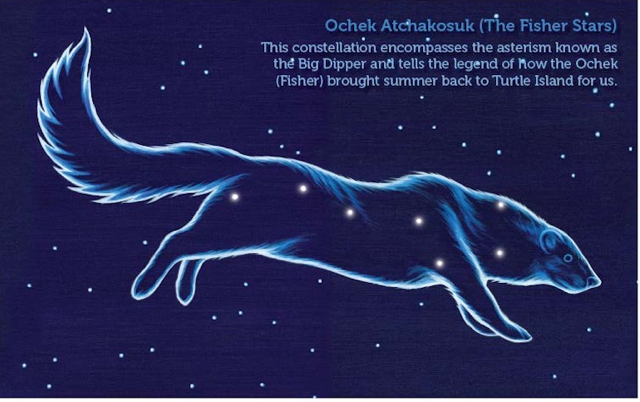

Image of the Ochek Atchakosuk constellation from MFNERC -The Arrow Newsletter. http://mfnerc.org/newsletter/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/The-Arrow-Jan-2015-Reduced1.pdf

A Cree story, once shared by the late storyteller Murdo Scribe, tells of the Ochek Atchakosuk, or fisher stars; you might know them as the Big Dipper. The fisher is a small animal related to the wolverine and is said to bring summer to the Northern Hemisphere, where once there was no summer at all. The story of the fisher may have originated in the ice ages, remembered and passed down for thousands of years. “When one includes the mythology of the people and begins to understand the thought processes behind the stories,” remarks Buck, “one begins to see depth, philosophy, and reason intermingled with the morals, social norms and teachings behind the mythology”.

Anyone who has ever worked with young kids knows how much they love stories, and storytelling may be an effective way to pass on information to young Canadians. The Cree Stars program teaches more than astronomy – it teaches history and cultural heritage. “It is important for First Nation students to come to realize that their people had scientific understandings, philosophy, reason, inventive and technological capabilities,” says Buck. “It was not only Romans and Greeks who went outside at night and looked up.”

“Wouldn’t it be great if an eager young student could go to the library and sign out a telescope for a weekend of star gazing?”

Nearly all the visitors at MacKenzie’s Open House had stories of their own to share. Inside the intimate inflatable dome of the Starlab, around 30 kids and parents sat in a circle – a configuration that allows for the best views of projected stars and planets, but also facilitates conversation. Back in Vancouver, mentioning the northern lights would have drawn little more than blank stares. In MacKenzie, however, it leads to long discussions of favorite places to watch the sky, and memories of family experiences under the stars. A friend once told me of growing up outside Fort St John and watching the aurora while waiting for the school bus. She described it as being so quiet that she could even hear the sounds the aurora made. I hadn’t even known it was possible to hear them until that conversation (apparently they make a crackling or whistling noise). It’s not just the northern lights that elicit this kind of reaction: the Milky Way, shooting stars, and constellations all bring about enthusiastic responses.

The greater connections with the sky found in smaller communities can lead to increased passion and wonder. Studies have shown that when high school students from larger cities are brought out to rural areas to view the night sky away from light pollution, enrollment in post-secondary astronomy programs increases. It’s difficult to be passionate about things we haven’t seen. So how do we fan the flames of passion that already exist in small communities?

Roaming programs and portable planetariums like those offered by the H.R. MacMillan Space Centre and the MFNERC help bring understanding to the enthusiasm. However, these programs are limited in the number of people and communities they can reach.

Advances in, and greater access to, technology are making astronomical information more universally accessible. Smartphones are increasingly common and numerous apps are now available for the casual astronomer at little to no cost. Google Sky Map and Night Sky are just two of several apps that can tell you in real time the names of stars, constellations, planets and other features of the night sky. For those without smartphones, virtual planetariums can be downloaded onto your home computer (Stellarium) or accessed online (like Neave, or In-The-Sky).

In the future, repurposing current resources in small towns could allow for more access to the stars. There are lots of great astronomy books aimed at young learners. However, libraries provide much more than books these days. “Many local libraries have been able to purchase robotic Lego or a set of Little Bits [electronics kits],” says Trish Pattison, but she believes that libraries could go further. Some branches of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada lend out telescopes to aspiring astronomers but these are generally only available in larger cities. Perhaps libraries could step up in smaller towns. “Wouldn’t it be great if an eager young student could go to the library and sign out a telescope for a weekend of star gazing?” asks Pattison.

Sadly, telescopes are not yet available at your local library and at the end of our evening in MacKenzie we had to pack up the Starlab and head back to Vancouver. The residents of MacKenzie made it abundantly clear that they valued our visit – one of the most common phrases heard from parents as they were leaving was a heartfelt “Thank you for coming here”, while many students emphatically described it as the “best day ever!” Bright minds in small-town Canada are thirsty for all the information they can get; we just need to find ways to provide it.

Header image: Milky Way (CC BY 2.0 Flickr )