Emily Olson, Communications, Outreach, and Education editor

Canada is known for its vast, pristine wilderness, which are a source of pride for many Canadians. Connecting with nature and enjoying the wilderness draws many people to the country’s parks. Visitors flock to places like Banff National Park or Kananaskis Country to hike, glimpse wildlife, camp, and take pictures of themselves in front of mountain vistas.

Since 2010, the number of visitors to Canada’s parks has increased steadily. Even during the pandemic, this trend continued, despite the restrictions on international travel. Some parks had to close due to high attendance. In a few cases, park registration websites crashed due to the demand for campsites.

Our desire to enjoy these rugged landscapes motivates us to protect them. High volumes of visitors can have adverse effects on the parks, including bad human-animal interactions and development pressures. Without land-use regulations and tourism management, the ecological integrity of these areas is at risk of being compromised. Parks Canada and Alberta Environment and Parks attempt to strike a balance between maintaining ecological integrity and supporting conservation initiatives and tourism by implementing a multi-faceted management approach.

A grizzly bear crosses a road in a park. This situation can either be a memorable wildlife sighting or a tragic human–wildlife encounter. Image by Eric Johnston, Public Domain Mark 1.0

High demand for Canada’s parks

Spring and summer are busy times in Canada’s mountain parks: bears come out of hibernation, many wild animals produce and rear their young, and visitors arrive at the parks in droves. With the rise in visitors comes an increase in human–wildlife conflicts, garbage, littering, injuries, illegal and unsafe parking, and overcrowding. The overuse of trails can lead to the trampling of plants, soil compaction, erosion, and damage to creeks and riverbeds. This can have lasting impacts on the natural landscape.

The summer of 2020 in Kananaskis Country is a case in point.

“[We] saw an unprecedented number of visitors and camping in Alberta Parks,” says Greg Part of Alberta Environment and Parks. “In Kananaskis Country alone, visitation was estimated at 5.4 million last year, or approximately 1 million higher than neighbouring Banff National Park.”

This increase in visitors puts a strain on a park’s infrastructure, which only adds to the park managers’ problems.

Christopher Smith, the Parks Coordinator for the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society (CPAWS) Northern Alberta Chapter says, “While the obvious answer might be to invest in additional infrastructure to enable these popular areas to safely handle more visitation, we must be careful that such changes don’t create an environment which degrades the park even more.”

If visitor numbers to the parks continue to increase, maintaining the balance between conservation and tourism will become more challenging.

What is being done?

In an attempt to support conservation efforts, the Government of Alberta introduced the Kananaskis Conservation Pass. The revenue from this fee is used to maintain services and facilities in the park and enhance conservation efforts. National parks already have an entry fee that contributes to the maintenance of the parks. Funding conservation initiatives can be challenging, especially with unreliable federal and provincial parks budgets. Tourism is an important way to generate financial and social support for these programs.

Inevitably, developed areas within parks, such as campsites, day-use areas, and townsites will attract wildlife. Human–wildlife encounters can occur when food and garbage are left out in campsites, people feed wildlife, or they stop to take photos of animals.

Habituated or problem wildlife is a continual problem in these busy parks. Animals can become conditioned to associate humans with food when people feed them directly or indirectly by improperly storing food or garbage. Some of these people–wildlife encounters may not end well, and they will only increase as the demands on parks increase. Unfortunately, park managers have few options, and the animals are often relocated or destroyed. This points to the need for investment in effective education and other management practices.

People need to act responsibly around wildlife for their own and the animals safety. Here, people photograph an elk in a roadside meadow. Image by Imarsman, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Education is a key strategy used by Parks Canada and Alberta Parks to ensure safe and sustainable tourism. In the late-1990s, human–elk incidents occurred at an all-time high in Banff National Park. Through education and the removal of elk from the townsite, these incidents dropped significantly. Although these types of interactions are still a problem in the park, combining wildlife management with education strategies has significantly decreased the severity and frequency of these events.

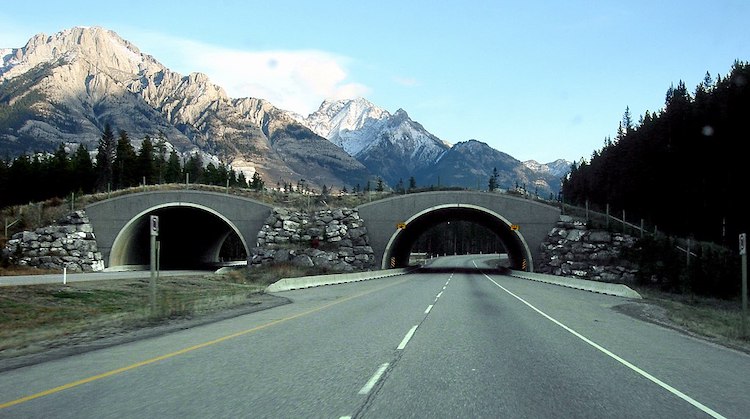

Parks Canada and Alberta Parks employ many techniques to manage wildlife, such as introducing bear-proof garbage containers, highway fencing, wildlife crossing structures, and wildlife translocations. Managing wildlife can be expensive, complicated, and disruptive to the animals’ natural processes, and it sometimes is ineffective.

A variety of infrastructure has been put in place to minimize wildlife–vehicle collisions. A wildlife overpass on the Trans-Canada Highway in Banff National Park allows animals to cross the highway. Image by Qyd, CC BY 2.5

A habituated grizzly bear in the Bow Valley, known to frequent the townsites of Canmore and Banff, posed a problem for wildlife managers inside and outside of the park’s boundaries. Incidents of bluff charges and close encounters were reported and the bear was relocated to remote parts of Banff National Park many times. In 2017, the bear was moved to Northern Alberta where it was legally shot by a hunter. A recent study found that only one-third of grizzly relocations are successful. Banff National Park no longer employs this strategy to deal with the problem. Instead, area closures and educational programs are used as a proactive approach to mitigate human–wildlife encounters.

Parks Canada’s Wildlife Guardian Program employs trained staff to manage bear jams along highways during the busy spring and summer months. They educate park visitors on bear safety, such as the appropriate distance to be maintained. They also provide advice on how to behave around wildlife and avoid close, possibly dangerous encounters with them. Parks Canada also holds Learn to Camp programs for beginner campers to learn about how to camp safely and respectfully.

Alberta Parks uses similar strategies to prevent negative people–wildlife encounters. It uses programs such as Alberta BearSmart, information and displays at visitor centres, and recreation and resource officers to educate the public. Alberta Parks also works with many nongovernmental organizations, community partners, and volunteers to fund conservation projects and help steward and support safe, sustainable tourism within Alberta’s parks.

Tourism plays an important role in creating awareness and community support for natural landscapes and provides funding for conservation initiatives. But unregulated tourism can have detrimental effects on the environment through pressures on park infrastructure, negative wildlife encounters, and impacts on sensitive ecological areas. Combining strategies to manage tourists, wildlife, and the environment is essential to maintaining wild landscapes. A balance between tourism and conservation becomes increasingly important as our natural spaces begin to disappear and demands on our parks continue to increase.

~30~

Banner image: Canadians visit parks and natural areas such as Kananaskis Country, Alberta to find natural beauty and pristine landscapes. Image by JD Hascup, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0