Katrina Brain, guest contributor

If you ever fall off your bicycle, you’ll want to be wearing a helmet. If you’re in a bike accident, a helmet could reduce your odds of a head injury by about 51 per cent, and reduce your odds of a fatal head injury by 65 per cent. This makes wearing a helmet seem like a no-brainer (pun-intended). After all, cyclists are vulnerable road users. Cars, other cyclists, pedestrians, and poorly designed biking infrastructure can all lead to crashes, even for the most cautious cyclist.

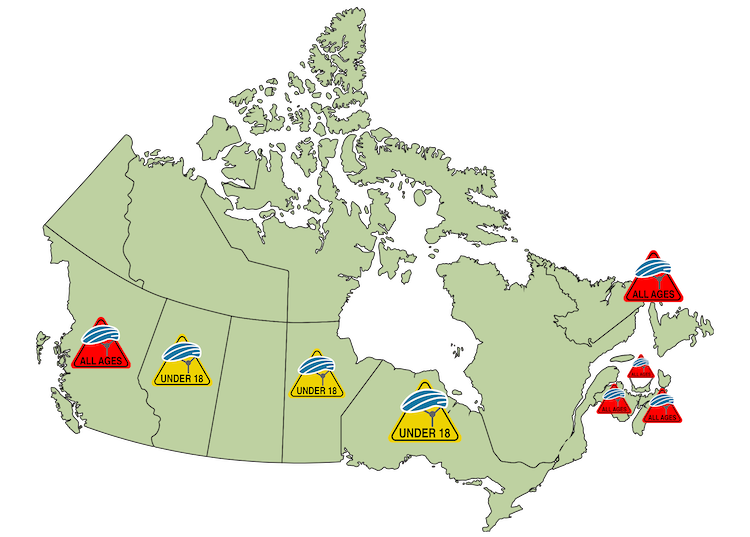

In Canada, from the mid-90s until 2012, an average of 74 cyclists died every year following a bike accident, and estimates show that only 17–33 per cent of these accidents were the cyclists’ fault. Some parts of Canada have responded to these fatality rates by creating helmet use policies: eight of the 13 provinces and territories have helmet laws that require either minors (under 18 years old) or all ages to wear helmets when they’re riding a bike. But with such convincing evidence on the benefits of wearing a biking helmet, why doesn’t every province and territory (or every country, for that matter) have a helmet policy? Because there’s a catch….

Eight provinces (and zero territories) have mandatory helmet policies. Image by Katrina Brain, used with permission.

In cycling, there is safety in numbers. If there are a lot of riders on the roads, drivers expect to see them and are usually watching for them. But helmet laws decrease the number of people who cycle, sometimes by 30–51 per cent, making it more dangerous for those who do ride a bike. If there are fewer cyclists, there is also less incentive to improve cycling infrastructure, which is another important part of cycling safety. So while on an individual level, it probably makes sense to wear a helmet, forcing everyone to wear helmets isn’t necessarily safer.

This surprising paradox means that there is a lot of published research on bike helmet policy. A 2013 study specifically looked at cycling-related head injuries in Canada before and after helmet legislation was implemented. The study found that helmet laws alone weren’t enough to affect hospitalization rates in a way that was statistically significant. Cyclist fatalities and head injuries were already going down when the Canadian helmet laws were put in place, and they’ve continued to do so. And while head injuries have decreased by a greater margin in places with helmet laws, they haven’t decreased by enough to rule out other influencing factors, like improved bike lanes.

Helmets may have a few unpleasant side effects on an individual level as well. Some research has found that cars pass closer to cyclists who are wearing helmets, giving them much less space on the road. While this alone probably isn’t enough of a reason for cyclists to stop wearing helmets, most serious cycling head injuries involve cars, so it is a definite cause for concern.

Another counterintuitive impact of helmet wearing could be ‘risk compensation’ – cyclists who are wearing helmets feel safe and protected, making them more likely to take risks on their bike. Risk compensation is often discussed in the academic research, but it’s hard to prove if it actually exists because it’s difficult to measure.

Helmet laws create other policy conflicts as well. British Columbia’s mandatory helmet laws for all ages posed a challenge when Vancouver first tried to introduce a bike share program (helmets were technically provided with each shared bike, but many were stolen and there were worries about pests like lice). Some cyclists in Nova Scotia, which has a similar mandatory-helmets law, are against the policy because they see it as a barrier to getting a bike share program, and getting more people biking.

Toronto has a thriving bike share, but these programs are much more difficult to create in places with mandatory all-ages helmet laws. Image from SamuelStone on Pixabay, CC0

Public health concerns compound the issue. Conditions like obesity, heart disease, and cancers are growing public health concerns and cycling regularly offers some major health benefits. One study found that over five years, people who commute by bicycle have a 41% lower risk of death from any cause, a 52 per cent lower risk of death from cardiovascular disease, and a 40 per cent lower risk of dying from cancer when compared to people with non-active commutes. If helmet laws deter people from cycling (by as much as 30–51 per cent), many people may miss out on the health benefits that come from getting outside and active on a bicycle. For that very reason, some places like Saskatoon have voted against introducing bike helmet policies, because they don’t want to deter people from becoming physically active.

Despite the evidence that might point away from helmet policies, a 65 per cent reduction in fatal head injuries for helmet-wearers can’t be ignored. Apparently, trying to make an evidence-based decision about bike helmet policy would require prioritizing some facts over others. So, what is a policy maker to do?

In this case, there doesn’t seem to be a ‘right’ answer. This means that decisions about which evidence to use to make policy are values-based. If you were a policy maker, would you value the public health benefits of cycling, and prioritize keeping more cyclists on the road? Or would you value the safety of a (possibly smaller) group of cyclists, and prioritize better outcomes for them in case of a crash? Would you try to straddle the two options by providing helmet education programs instead of a law, like in Quebec and Saskatchewan? Or, would you try a different approach altogether and focus on creating better bicycle paths? In the case of bike helmets, making a policy that is evidence-based is a lot more complicated than just gathering all the data

Regardless of helmet-policies, I put on my helmet every time I get on my bike – I feel vulnerable without it. And I think you should probably put on your helmet, too (odds of a fatal head injury reduced by 65 per cent? Yes, please!). But do I think that all of the provinces and territories should adopt all-ages helmet policies? Based on the available evidence on the subject, I really can’t say.

~30~

Banner image: Pixabay, CC0

Very well explanation you provide, thanks a lot. I am looking such like this post before I buy . I got hesitate but now I feel free to buy my desired on.

Thanks again.

I always put on a helmet when I’m going to cycle in medium to high-speed traffic areas >50kph (>30mph).

I never put on if I’m staying in low-speed to no traffic areas <30kph (<20mph). And in between it varies.

I think an official helmet requirement by law should consider this and depend on the speed limit of the traffic your riding your bike in.

As you say, "most serious cycling head injuries involve cars".

Nice post!