Lauren Borja, Physics & Astronomy editor

Millions of people gathered to watch the moon completely obstruct the sun today during the Great American Eclipse of 2017. While the path of totality didn’t pass through any part of Canada, much of our nation was treated to a partial eclipse during the middle of the day.

But why were scientists and Canadians in general so excited? There are certainly some experiments that were be done during this total solar eclipse, but the buzz and enthusiasm went beyond an interest in facts or discovery.

An Atypical Alignment

To understand some of the excitement surrounding the eclipse, I talked to Dr. Christa Van Laerhoven, a postdoctoral fellow in astrophysics at the University of British Columbia (UBC). Van Laerhoven studies the orbits of planets and how they change over time. Using computer models, she explores the theoretical extremes of the universe – questions such as how many planets can fit into the habitable zone of a star before they start to collide with one another. Van Laerhoven is an expert on how things move through space.

Dr. Christa Van Laerhoven, astronomer at the University of British Columbia. Image © Armin Mortazavi.

Solar eclipses look spectacular because the Sun and the Moon appear to be the same size in the sky (explained in a previous Science Borealis article). Because of this, the Moon completely obscures the area of the sun that emits light, known as the photosphere during a solar eclipse. People in the path of totality looked into the sky and saw the Sun completely covered by the Moon for a few brief minutes.

This moment of totality, Van Laerhoven says, was “actually a peculiarity of the time in which we are living.” The orbit, or circular path around the Earth, of the Moon slowly expands at a rate of 3.8 cm per year. Scientists measure the expansion of the Moon’s orbit very precisely by shooting lasers at a series of reflectors that the Apollo astronauts left on the Moon. Over time, total eclipses will no longer be possible, because “the Moon will be far enough away that its apparent size will be too small,” say Van Laerhoven.

It’s probably a little too soon to get worried, though. It’s going to be at least another 600 million years before the Moon’s orbit expands the additional 23,500 kilometers needed to make total solar eclipses a thing of the past.

Excitedly – the Best Way to View an Eclipse

Even more extraordinary, the eclipse brought together all sorts of people to appreciate science. This confluence was especially exciting for science communicators like Armin Mortazavi, a science cartoonist. Originally hoping to become a doctor, he studied microbiology at UBC before doing a master’s degree in digital media at the Centre for Digital Media.

“The cartooning thing isn’t new,” Mortazavi says, “I’ve been doing that since I was five.” Over time, Mortazavi has taken his artwork from doodles of cats that littered the margins of his microbiology notes to a series of characters in an interactive children’s comic on health issues.

Through his cartoons, Mortazavi establishes a connection with his audience. In the age of the internet, this connection provides the momentum for a person to “go off on their own and explore,” he says.

Mortazavi’s exuberance around the eclipse came more from a general love of space than from a mathematical appreciation. For his presentation at an eclipse-themed event, he drew inspiration from the awe he feels when he looks at pictures of space.

These emotions are key for Mortazavi, who sees them as an important part of his science communication. People today no longer expect one scientist or communicator to provide all the facts or knowledge. In the age of the internet, many of these facts are readily available at the click of a button. Mortazavi instead focuses on exciting people and giving them the needed momentum to become interested in a topic, such as the eclipse or astronomy.

His experiences learning about space as a child support this theory. He fondly remembers a lesson on the planets he received as a kindergartener from an excited older cousin, describing her passion for the subject as contagious.

Most importantly, Mortazavi says “you don’t have to be a physicist or an astronomer to enjoy space.”

Black Hole Sun, Won’t You Come?

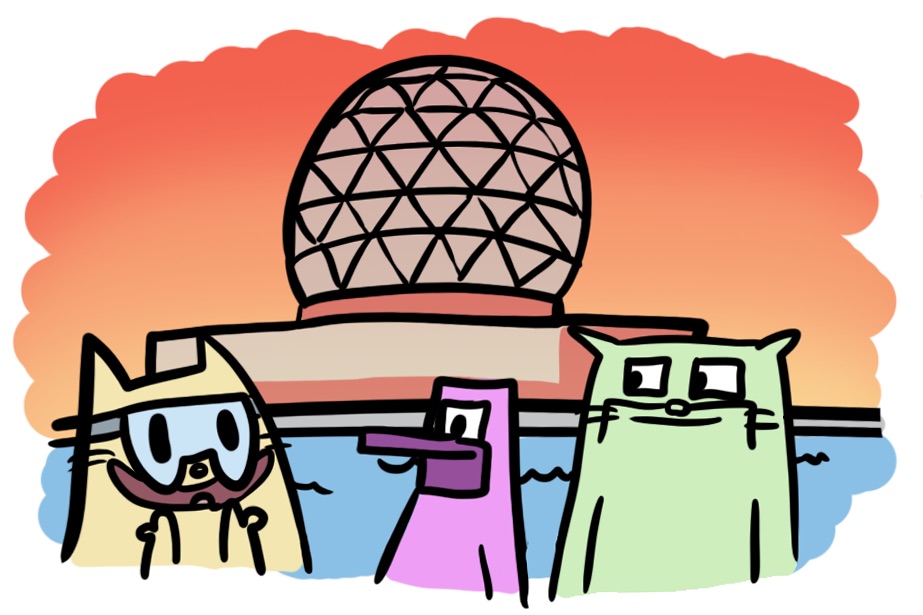

Indeed, many scientists and non-scientists came out to appreciate the eclipse. In Vancouver, the local chapter of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada (RASC) hosted an eclipse-viewing party at the TELUS World of Science. And while many people came from different backgrounds or used different equipment to view the eclipse, everyone enjoyed sharing their experience with the crowd.

Characters of all types gathered at TELUS World of Science for an eclipse-viewing party. Image © Armin Mortazavi

Members of the RASC shared many different devices for viewing the eclipse. Robert Conrad, observing director of the organization’s Vancouver chapter, demonstrated how to use a sunspotter, a simple solar telescope formed by a lens and two mirrors that projects a larger version of what you’d see using a pinhole camera. An exuberant explainer, Robert hoped that this demonstration “encourages people to get involved in [astronomy] as a hobby.”

William, who has been a member of RASC for over 30 years, brought his own favorite telescope, equipped with the proper aluminized mylar filter, for gazing at the sun. And while things got a little busy during the eclipse maximum, he “just like[d] sitting there and enjoying the ambiance.”

The eclipse was also an opportunity for amateur photographers to share in the excitement. Bob photographed the sun through a solar filter and enjoyed sharing pictures of the maximum with the crowd. “I’m glad I came down here, rather than stay at home,” he said, “when it reached maximum, everyone clapped and cheered.”

Matt, another amateur photographer, focused his camera on the environment and people instead of the sun. He was happy to catch people “paying attention to the world around them.”

Despite the presence of news trucks at the Telus World of Science eclipse-viewing event, it is unlikely that this viewing of the partial solar eclipse generated new science. But maybe the next generation of physicists and astronomers will trace their moment of inspiration back to the Great American Solar Eclipse of 2017.

More of Armin Mortazavi’s work can be found on Instagram (@armin.scientoonist) and YouTube (TheScientoonist).