Jasleen Grewal, Communication, Education and Outreach editor

This decade is undeniably off to a scary start, what with the Australian bushfires, the Persian Gulf crisis escalation, and now, the COVID-19 pandemic. We thought it would be a nice break from current events to look back at the last decade and collate some of the popular science stories that captured our collective imagination – many related to innovative research by Canadian scientists.

What’s on your plate today?

The 2010s offered up multiple food fads and breakthroughs in food processing – from the keto diet to Beyond Meat® burgers to bug butter. While many of these dietary innovations were beneficial because they reduced the environmental footprintfood production, some focused on helping people lose weight. The keto diet, for example, is a low-carbohydrate diet that removes glucose from food intake, forcing the body to break down its fat reserves for energy. The diet’s potential health benefits and long-term impacts remain to be seen, but the molecular mechanism it targets has an interesting Canadian tie.

The keto diet bumps up the amount of leptin in the bloodstream. Leptin is a key metabolic hormone that regulates our feeling of hunger – increased leptin levels tell the brain that the body is not starving and that there is enough energy stored in fat cells to continue normal activities. Leptin was touted as the ‘fat loss hormone’ long before the keto diet rose in popularity.

But did you know that this hormone was jointly discovered by Dr. Douglas Coleman, a Canadian scientist, and Dr. Jeffrey Friedman in the 1990s? They discovered that leptin can regulate appetite and body weight – research that revolutionized the use of molecular approaches for studying obesity. The duo was recognized for this contribution in 2010 with the Albert Lasker Basic Medical Research Award, one of the premier awards for major contributions to medical science.

Do you see what I see?

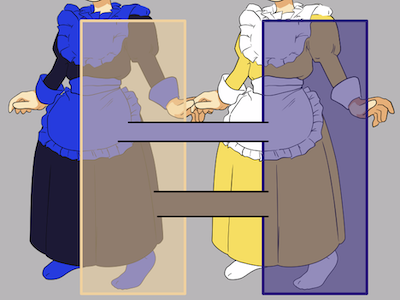

Figure design by Kasuga~jawiki; vectorization by Editor at Large; “The dress” modification by Jahobr, CC 2.0

In 2015, we had a collective whoa moment with The Dress. The original photograph was of a blue dress with black trim, but the dress was perceived as white and gold by many people. As the dust settled over the 5 million tweet-opinions, scientists from research areas such as vision and psychology tested theories to explain the widely varying perceptions of the same photograph.

While there is still no consensus, the widely accepted explanation is based on the way we perceive colours. The first large-scale study on this matter asked 1,400 people what they saw when given differently illuminated versions of the dress. The researchers concluded that how the respondents perceived the dress was determined by how their brains processed the colour of the illumination source. Depending on whether they perceived the photo to be lit by cool blueish light or warm yellow light, people discounted either the blue hues (and saw white/gold), or the yellow hues (and saw blue/black).

But why did people perceive the illumination source differently? One explanation, based on research using more than 13,000 online surveys, is that people who spend more time in sunlight (which contains significantly more blue than artificial light) assume the illumination in the photo is blueish and filter this out, consequently seeing the dress as white and gold. In contrast, ‘night owls’, who are more routinely exposed to yellowish incandescent light, assume the illuminant in the photograph is yellow and filter that out, seeing the dress as blue and black. Other researchers observed that, when the dress was shown in strong artificial yellow-coloured illumination, almost all respondents found it to be black and blue, and when it was shown with a simulated blue source of light, most saw it as white and gold.

While there’s no concrete explanation yet for the phenomenon of The Dress, the underlying concept of colour constancy is ever-present in our daily lives: we learn to unconsciously correct for illumination tone depending on what type of illumination we are usually exposed to.

The theory of colour and visual perception spans science and art, and there is a vibrant (pun intended) community of artists, scholars, and designers in Canada who work in this area. You can learn more from the Colour Research Society of Canada – Canada’s only colour-focused non-profit organization. Colour constancy and its impact on our daily lives also remains an active area of study – read more here about researchers working on computational methods for studying colour constancy at Simon Fraser University.

Back to the future: Are we there already?

It seems like science fiction – kick back with a mojito in the backseat of your car while it drives itself (and you) to the grocery store. But if the last decade’s breakthroughs are any indication, self-driving cars might be commonplace by the middle of this century.

To some degree, ‘self-driving’ capabilities have been available for a while now – automated tools like cruise control and lane assistance are quite common in modern cars, thanks to research from as far back as the 1940s. However, innovations in artificial intelligence (AI) over the last 10 years have helped pave the way for autonomous cars that are truly ‘hands-off’ and require minimal human intervention – be it whizzing around town or going on long road trips.

For a car to be fully autonomous, it needs to constantly monitor its surroundings and react to them, much like a human being. By combining AI with cameras, lasers, and other sensors, researchers hope to train machines that are capable of monitoring changing surroundings and making decisions dynamically, just as humans would. From Tesla’s self-driving truck, to GM’s futuristic car without a steering wheel, to New York City’s self-driving shuttle service, these capabilities are now being tested and steadily making their way to reality. That said, the rising enthusiasm has been tempered by debate about how similar the AI driving these cars is to actual human intelligence and ‘common sense’. Current AI relies on training computers with multiple virtual scenarios, but this approach is prone to pitfalls. For example, what happens if the machine encounters a scenario it was never taught – such as driving in areas where there is limited data on routes and traffic? Can we trust these machines to know what to do in such circumstances?

Last year, the Turing Award – considered the Nobel prize of computing – was presented to three computer scientists for their decades of research in AI: Dr. Yann LeCun, and two Canadians, Drs. Yoshua Bengio and Geoffrey Hinton. At a conference earlier this year, the trio emphasized that current AI is far from the machine equivalent of common sense, a sentiment shared by others in the field. Because these systems might encounter uniquely complex situations when they are deployed in routine life, researchers believe it is not sufficient to evaluate their performance on contrived scenarios and specific tasks. There are many minds working on developing and measuring human-like intelligence in computers, which may eventually lead to AI-powered autonomous driving technology that we can rely on. But for now, that mojito-sipping chauffeured car-ride remains the stuff of dreams.

~

We are surrounded by science – in every tool that makes our lives easier, tastier, or weirder. Here, we showcase just three of these popular science stories and how they tie in with cutting-edge scientific research.

Are you a science aficionado? Maybe think about how you can discover and explain some of the connections between news stories and hardcoreTM science – a handy conversation starter the next time you hang out with your friends (post-social distancing, of course).

~