Raymond Nakamura and Lisa Willemse, Multimedia co-editors

*Revised 29 Sep 2014 to include previous film award won by Suraaj Aulakh.

Anyone with a mobile phone can shoot a science video and put it on YouTube, just like anyone with a computer can write a science blog. There’s a difference, however, between just creating content, and creating content with which people will actually engage. If you pegged money as the biggest driver of the two, then it might surprise you to know that, while money can be a limiting factor, it’s not necessarily the most important (i.e., if Avatar CGI is your vision but you’ve only got $100 in your budget, you may need to think small models on a black screen (Ã la the original Star Wars) or claymation (Ã la Nick Park)).

We contacted two Canadian science multimedia production teams to ask what it takes to create good video content, and what they felt were the most important elements in the creation of their series (think goals, audience, and the power of a good script).

The first duo is Mike Long and Ben Paylor of InfoShots, who produced the award-winning StemCellShorts series of 60-second animations that explain the basic concepts of stem cells to teens and young adults. They currently have four videos, with four more in production. The second is a group of Banff Science Communications program alum (Suraaj Aulakh, Pam Lincez, Agatha Jassem, Theresa Liao) who have come up with The Lab, a recently released YouTube comedy series about grad students working in a science lab.

StemCellShorts

One of the key elements for Paylor and Long was having a clear idea of what they wanted to communicate, and to whom. “Anyone who has spent time searching the Internet for quality educational materials will no doubt have encountered these common problems: there’s loads of stuff out there, and it’s generally burdened by excessive jargon, long running time, and visual styles that aren’t exactly appealing to the general public. Our goal was to address this gap by creating videos that are simple, short (60 seconds), and produced in an engaging visual style.”

A second and highly important consideration is the quality of both the work and the collaborators involved. Says Long, “The StemCellShorts team is much bigger than just Ben and me.” The script, for instance, goes through several iterations, including review and edits by the Stem Cell Network Public Outreach committee (comprised of five people with science and/or science communication backgrounds), and by the professor providing the narration.

Then there are the visuals and sound, with which Paylor and Long have developed excellent connections, including animation by David Murawsky and a soundtrack by Leo-award-winning sound designer, James Wallace. Says Long, “Of course the biggest challenge with a diverse team of this size is co-ordinating schedules. It seems as though each piece is constantly awaiting input from someone. However, the wait is usually worth it. As the product of a diverse team, each video is much, much better than anything Ben and I could have done on our own.”

They’ve hit a magical combination of intent, talent, and creativity with StemCellShorts – earlier this year, the first three videos in the series received an honourable mention in the 2013 Visualization Challenge, awarded each year by Science magazine and the National Science Foundation.

This, while on a very conservative budget. To keep costs low, Paylor, a PhD student at UBC and Long, a postdoc at the University of Toronto, decided to create a production business (InfoShots) through which they handle all the production and workflow. Long and Paylor received several seed money grants (the first three videos were funded by the Stem Cell Network (SCN), and the second set of five were funded by SCN and matching funds from the Canadian Stem Cell Foundation) to help get their projects off the ground and, importantly, to help with promotion once complete.

Balancing grant timelines with production can be a challenge for the team. Typically, each video takes about six months to produce, from script to launch and promotion. However, this is time expended in off hours, between full time lab work and a myriad of other commitments held by Paylor, Long, and their collaborators. In an ideal world where the team could work at Infoshots full time, Long estimates that each video could be completed in a few weeks.

Note that not all costs are covered: Long and Paylor do all the script writing, storyboarding, and project management for free, allowing them to direct the grant money through Infoshots to other production costs. It’s a model that has worked well for the team, enabling them to maintain good relationships with their collaborators and to leverage their skills into additional work — two complementary video series for the University of Calgary are also underway.

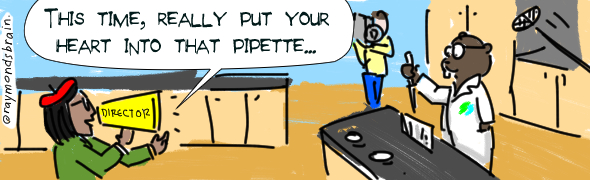

The Lab

As producer and director of The Lab series, Suraaj Aulakh describes herself as “a scientific videographer and animator, and founder of @labtricks.” Labtricks is a web site of videos to help science students learn various techniques to use in the lab – a concept for which Aulakh has won a business award and Gene Screen BC‘s short film competition.

For The Lab, the team of Aulakh, Lincez, Jassem, and Liao took about a year to write the scripts and then filmed it in a week. On her blog, Liao reveals that the writing process included many meetings, Google hangouts, edits, and rewrites. After the first scripts were written, the team got busy with other work and the project stalled. “But at some point,” says Liao, “Suraaj continued – huge kudos to her. By the time we got another email about this from her, it was a year later, and the scripts for a few more episodes had been written. In fact, she had started looking for actors and actresses for the show.”

Currently, the teaser and the first two episodes are available, and the team has been releasing episodes as they edit them.

The Lab targets scientists of all stripes: aspiring, working, and recovering. Aulakh told me in an email, “sometimes the workload and stress can be overwhelming, and we hope this series will give viewers a reason to laugh at some of these things and realize that they are not going through this alone.”

The Lab’s Facebook page also references Jorge Cham’s PHDComics, which deal with life in academia. Cham aims to fill the communication gap between scientific discoveries and the public, as well as the perception gap in how the public understands scientists and what they do. Cham is particularly concerned about how shows like Big Bang Theory depict scientists – something that The Lab is also focused on. “…On film and television, scientists are presented as anti-social nerds, or geniuses who know the answer to everything. In reality, most scientists (and science grad students) are normal individuals with normal interest,” says Aulakh.

We’re not sure about normality. 🙂 But it might just be this off-kilter normality that will make The Lab a series worth following, especially for those who recognize themselves or their own workplace in The Lab’s fictitious world.