Alina C. Fisher and Tanya Samman, Environmental and Earth Sciences co-editors

While looking out your office (or home office) window, do you give any thought to wildlife? Many city dwellers may not think about wildlife often during a regular day. We don’t see bison roaming our city streets or cougars in the trees of our local park, but that doesn’t mean that we don’t coexist with wildlife.

You might think of wildlife as living in the wilderness, far away from our daily urban lives. But many wildlife species have adapted to cities and are a part of our urban ecology. From the backyard birds we feed to the pesky raccoons that get into our garbage cans, many animals have learned to share space with people through behavioural changes.

How do species coexist? First, we need to consider an ecological concept called a niche, which explains why species exist where they do. A niche is the sum of the environmental conditions a species needs to survive. This includes food/prey, mates, dens, and the ability to avoid competitors or predators. It’s the balance between gaining benefit (obtaining food) and potential loss (predation). Animals achieve this by selecting living areas that are the optimal combination of maximum opportunity and minimal risk. In this way, animals can coexist in the same space by using different resources.

Likewise, in natural areas, competing species can often coexist in the same space even if they use the same resources through a process called temporal niche partitioning: they avoid each other in time. As Sandra Frey, Research Associate in Environmental Studies at the University of Victoria, explains, “For species to be able to share a habitat or landscape, they have to find ways to avoid each other. That can be done by using different spaces or eating different foods, or by avoiding each other […] by being active at different times of the day – when the other species are less active. Like, being active at night while their competitors might be asleep.”

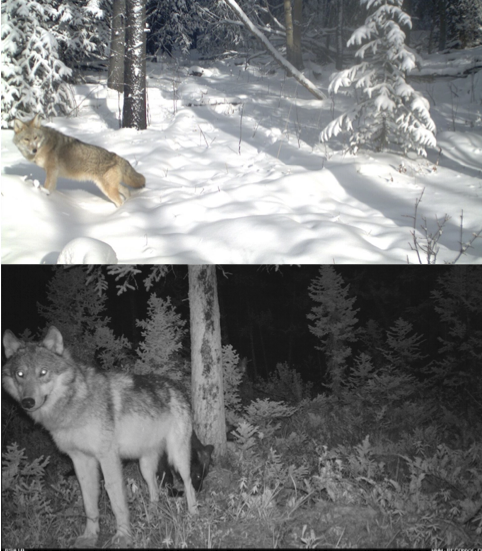

Coyotes (top) and wolves (bottom) adapt to the presence of humans in different ways. Coyotes increase their active period from twilight to throughout the day, while wolves shift their active hours towards the night. Photos: Alberta Environment and Parks, used with permission

Many species use temporal niche partitioning to coexist with humans. Recent studies show animals shift their activity patterns in places where wildlife and people are both found. By foraging at times when people are less active, wildlife can be less visible to people. For example, Dr. Clayton Lamb, a Wildlife Scientist at the University of British Columbia – Okanagan, found that grizzly bears across British Columbia shift their activity patterns to night. In most cities, everything – other than highways and trains – shuts down at night, so being active at night means bears can minimize the risk of conflict with people while finding food.

Grizzly bears are among the wildlife species that have changed their behaviour to share space with people. Photo: Dr. Clayton Lamb, used with permission

However, Lamb found that grizzly bears responded differently depending on their age. Older bears tended to change their active hours to nighttime, but not all younger animals did. Lamb indicated that “those are the animals you see on TV in Banff or Fernie. They are usually young animals that haven’t yet learned to take advantage of the quieter and safer periods of the night.”

Some animals need to worry about avoiding species other than humans. Frey also found that being more active at night increased survival in some species, such as wolves. However, smaller animals like coyotes need to avoid larger predators like cougars and wolves as well as people, so they are faced with a more complex balancing act. Frey found that although coyotes tend to be active at twilight in wilderness areas, they moved their activity to daylight hours in areas where they also have to coexist with people.

Frey points out that this shift in behaviour raises questions. “Is this a response to how humans have changed the configuration of the landscape [itself], or the distribution and availability of resources on the landscape? Or perhaps [it’s] just that the presence of humans might change the behaviour and distribution of top predators which can, in turn, affect the behaviour and distribution of smaller predators like the coyote.”

The change in activity patterns may not seem like a big deal, but it could have a cost. Human-induced behavioural changes affect species differently and cause cascading ecosystem effects. For example, animals that have adaptations for their prime activity period, such as the ability to see best during the daytime, may be less effective hunters if forced to hunt at night. Temporal niche partitioning may also have significant implications for wildlife conservation because of the resulting changes in how wildlife species interact with each other.

Although temporal niche partitioning may allow wildlife to coexist with people, the long-term effects on animals remain to be determined and may not be positive. People should take this into account when building their environment, and consider the need to limit interactions between wild animals and people.

~30~