Esme Symons and Sri Ray-Chauduri, Technology & Engineering editors

Plastic items, including single-use plastics, are ubiquitous throughout Canada. When we’re done with a disposable water bottle, many of us will spot a recycling symbol and throw it in a recycling bin, believing we’ve given the material a new lease on life. However, with Canada recycling only nine per cent of plastics, can we be sure this is the case?

Plastic that doesn’t get recycled takes up precious space in landfills. Recycling this plastic would reduce both plastic waste and the need to extract new resources. Image by Michelle Arseneault, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0

Why recycling is complex

Recycling makes sense from the conserving materials perspective. But the environmental impacts of recycling are complicated. What happens to a plastic item after we put it in our recycling bin, and what are the consequences? How much energy does it take to transport the item to the recycling facility? Is it shipped across the planet or processed locally? Once at the recycling facility, how much water and energy are required to process the plastic? Are emissions released into the atmosphere during the recycling process? Once a new product is made, how does it get back into the hands of consumers? Cost is also critical. If it works out to be cheaper to create new plastic, how can we make sure recycling occurs?

A life cycle assessment is a tool for understanding the full impact of a product. A ife cycle assessment tracks impact from cradle-to-grave or cradle-to-cradle when recycling. The energy use, material use, and waste created at each stage of a product’s life are quantified. This calculation can include extraction of raw materials, manufacturing, any transportation involved, use, maintenance, and disposal or recycling.

Why plastic is complex

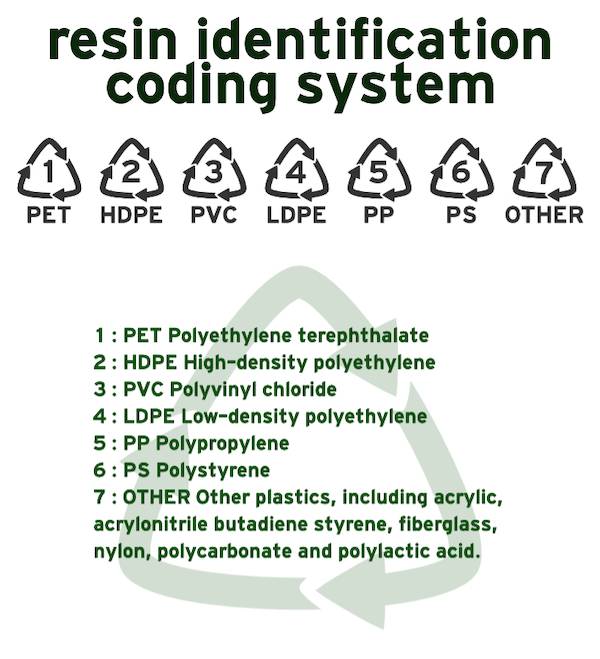

Most plastic products are labelled with the resin identification coding system. Image by Filtre, Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0, modified

The word plastic encompasses a wide range of materials. Plastics are polymers – repeating molecular units linked into chains – mixed with other additives. Different plastics have different properties and require different treatments when it comes to recycling. A soft, flexible grocery bag mixed into a batch of more rigid plastics, like shampoo bottles, alters the properties of the resulting recycled material.

Manufacturers often label plastic packaging with a resin identification code. Confusingly, the number inside a recycling symbol doesn’t always mean the plastic is recyclable; rather, it indicates the type of plastic. Plastic items marked with “1” or “2” are among the most widely recycled plastics; however, recyclability depends on what your local recycling facilities accept. Recycling programs in many small communities do not accept or collect low-value recyclables.

Plastic recycling: A complicated process for a complicated material

After the plastic has been collected for recycling, it needs to be cleaned and sorted. The easiest way to do this is to require citizens to clean and separate their recyclable materials before collection. Unfortunately, this extra individual effort may discourage some people from recycling.

At a recycling facility, there are a variety of automated plastic sorting methods. Airstreams lift low-density plastics from the general plastics stream. Optical methods, such as near-infrared systems, detect the chemical composition of the plastic by shining light on the plastics and measuring its reflection. Black plastics aren’t accepted for recycling everywhere because the pigment makes plastic-type detection difficult. Light sensors are also used to sort plastics by colour. Mixing multiple colours results in a less visually appealing product, making the recycled plastic less valuable.

A mechanical process breaks down plastics into small pieces that are melted and reformed for recycling. One major drawback of this process is the degradation of the plastic’s quality. Each cycle shortens the polymer chain length, making the material more brittle. In some cases, a bottle won’t become a new bottle. Instead, the bottle may be downgraded into fibres for synthetic textiles such as polyester fleece, which won’t be recyclable again.

One alternative to mechanical processing is chemical recycling, which can theoretically make plastic indefinitely recyclable. This process breaks plastics down to their chemical building blocks, which can be used as fuel or raw materials to produce new high-quality plastics. However, chemical recycling still needs to be proven feasible on a large industrial scale, and there remain potential environmental concerns to address.

Snapshot of three different municipal recycling programs in Canada

Communities across Canada deal with recycling in different ways. Some communities require people to take their recycling to a depot while others pick it up curbside; some require sorting, others do not. The three examples presented here differ primarily by population size.

- Agassiz, British Columbia (population (2016): under 6067)

- Residents must take recycling to a depot or pay for private curbside pickup.

- Single-stream private pickup: all recyclables are mixed in a translucent blue bag. Optional sorting at the depot.

- Types of plastics NOT accepted include foam packaging and plastic bags (depending on the choice of collection company).

- Vancouver, British Columbia (population (2016): 631,486 (largest in British Columbia))

- Curbside pickup.

- Multistream: residents sort plastics from paper, metal, and glass but do not sort by type of plastic.

- Types of plastics NOT accepted include foam packaging and plastic bags unless taken to a depot.

- Toronto, Ontario (population (2016): 2,731,571 (largest in Canada))

- Curbside pickup.

- Single stream: residents do not sort recyclables.

- Types of plastics NOT accepted include black plastic.

Our current approach to plastic recycling is inconsistent, unintuitive, and inefficient. New recycling methods are needed. Two Canadian companies have teamed up to develop technology that creates ethylene from waste that isn’t mechanically recycled. Ethylene is a component of new plastic or other products like antifreeze. Researchers are also exploring using bacteria and enzymes to break down plastics. If these types of projects can be sustainably scaled up, they could increase plastic recycling rates and propel Canada towards a zero plastic–waste future.

~

Recycling is the process of converting old or used materials into new products and there are many social benefits of it.