By Sonja Soo, Environmental & Earth Sciences editor

Many people know that they risk contracting Lyme disease — a serious illness with symptoms such as a bullseye-shaped rash, fever, chills, fatigue and headaches — if they venture into tick-infested areas. You can contract Lyme disease if a tick carrying a specific bacterium called Borrelia burgdorferi bites you. But ticks can carry and spread many other pathogens that are harmful to human health.

What’s even more concerning is that some tick-borne pathogens were recently found outside their known geographical range. In a study published in November 2022, researchers at McGill University and the University of Ottawa reported finding ticks and small mammals carrying two pathogens, Babesia odocoilei and Rickettsia rickettsii, outside their established risk zones as outlined on the provincial and federal government websites.

“For Babesia odocoilei, this is the furthest southeast in Quebec that we’ve located it, and for Rickettsia rickettsii, this was the first time it has been found in Quebec,” says Kirsten Crandall, a Ph.D. candidate at McGill University and the University of Ottawa and first author of the study.

As an ecologist, Crandall has spent many hours collecting ticks and testing them for pathogens in various areas in Quebec and Ontario. Both Babesia odocoilei and Rickettsia rickettsii can cause severe illnesses. Babesia odocoilei can lead to babesiosis, with symptoms such as fever, fatigue, headache, and gastrointestinal symptoms. Rickettsia rickettsii can lead to Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, with symptoms that include fever, headache, rash, nausea, and vomiting.

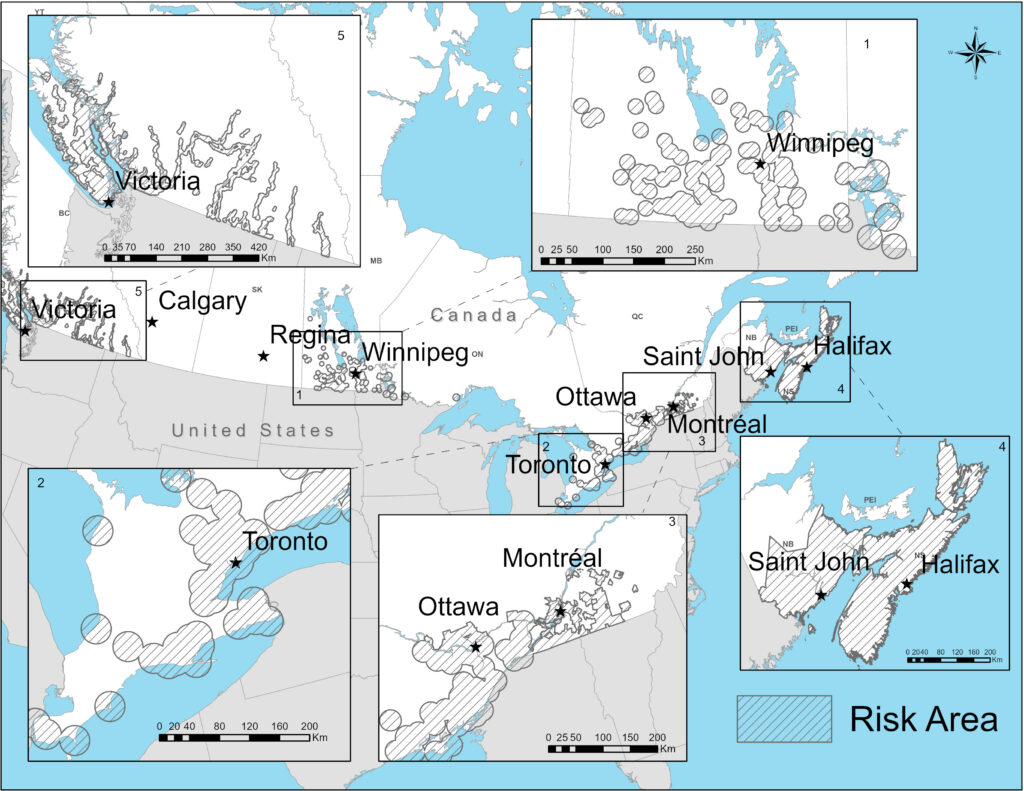

This map shows five areas of known risk of tick bites and Lyme disease. Image: Cross-section map of 5 areas known for risk to tick exposure, 2022 from Government of Canada website.

Tick-borne illnesses expected to rise in Canada

There are over 40 species of ticks found in Canada. The most concerning are the black-legged ticks and Western black-legged ticks since these species can carry and transmit various pathogens that affect people, including the pathogens that cause Lyme disease and babesiosis. These ticks are very small, about the size of a sesame seed. They perch on grasses, bushes and trees and latch onto people when they brush against them. The ticks then move to a hard-to-see area (groin, armpit, scalp) to feed on the host’s blood. An infected tick transmits pathogens to the blood host as it feeds: it can take as many as 24 hours of feeding to transmit the Lyme disease bacteria to the host.

More ticks and an increased incidence of Lyme disease have been reported in recent years. According to Health Canada, a record-breaking 3,147 cases of Lyme disease were reported in 2021 alone — almost double the number of cases reported in 2020 — including patients who contracted the illness in Canada or while travelling abroad. The real number of cases is probably higher since some cases are undetected or not reported.

Other tick-borne illnesses are less common here but expected to rise. For example, babesiosis is rare in Canada, with the first case reported in 2013. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the number of infections is rising in the U.S., with a total of 2,418 cases reported in 2019.

Currently, the Government of Canada is only mandating the reporting of Lyme Disease and tularemia cases, though many other tick-borne pathogens have been recorded across different provinces. As these pathogens spread, Canada is seeing emerging illnesses such as anaplasmosis, babesiosis, Powassan virus, and Borrelia miyamotoi disease. The lack of reporting (and awareness) has consequences. In one case study, an individual in Canada spent six weeks with undiagnosed babesiosis until their blood was analyzed further and their ailment identified.

Environmental changes and tick-borne pathogens

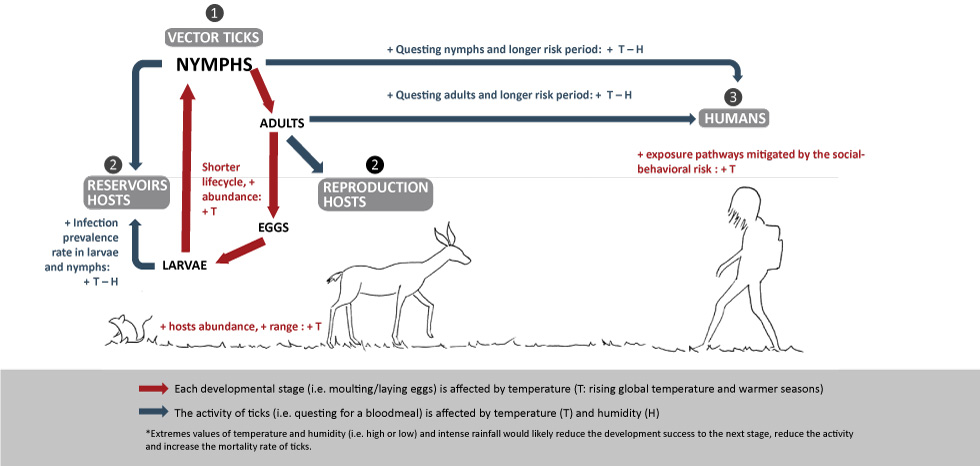

The black-legged ticks that spread babesiosis and Lyme disease are expected to become more common in Canada as a result of environmental changes. Increased temperatures due to climate warming allow ticks to survive better in the winter and reproduce more, leading to increased tick abundance, activity and spread. A rising tick population means more vectors for transmitting tick-borne pathogens.

Climate change also impacts ticks’ host animals. Younger ticks, called nymphs, may become infected with pathogens when they feed on wild rodents, such as mice. Adult female ticks rely on hosts such as deer as their source of bloodmeal in order to reproduce. With increasing temperatures, these animal hosts have expanded their ranges, increasing the opportunities for the spread of tick-borne illnesses.

After hatching from eggs, young larval ticks feed on reservoir hosts, such as mice, and may become infected with pathogens. Adult female ticks feed on reproduction hosts, such as deer, for their bloodmeal. Infected nymphs and adults may bite and feed on humans and cause illnesses. Different species of ticks may feed on different animals. The life cycle of ticks is affected by air temperature and humidity. Image: Government of Canada, adapted from Nick H. Ogden and L. Robbin Lindsay, CC BY 4.0.

Climate change has also affected the migration patterns of birds that can carry ticks and spread tick-borne pathogens. Hundreds of bird species are migrating earlier each spring. Some birds in North America have begun migrating further north. Birds migrating north from the U.S. are thought to bring ticks and their pathogens to Canada.

Other environmental changes such as forest fragmentation, in which larger forested areas are divided into smaller patches, can increase the risk of tick-borne pathogens since they can affect the abundance of host animals that carry ticks.

Awareness and more comprehensive testing are needed

Since many of these tick-borne illnesses have overlapping symptoms such as headache, fever, and muscle pain, it is important for health care providers to be aware of these emerging pathogens and test for them. The researchers who wrote the 2022 study are calling for more comprehensive testing and tracking of tick-borne pathogens in order to monitor the risk of illnesses.

“If you go to your doctor, and you have these symptoms, they might think it’s Lyme disease when it’s actually another tick-borne illness like anaplasmosis or babesiosis. It becomes difficult to get the proper treatment for other tick-borne illnesses, especially if you’re only testing for Lyme disease or receive a negative Lyme disease test,” says Crandall. Awareness of the different tick-borne pathogens that might be in an area is important, she notes. “You should be alert even if you’re not in a high-risk area because it is possible that ticks are present there, which may be infected with a pathogen.”

Typically, these illnesses are treated successfully with antibiotics. Early diagnosis and treatment are crucial for preventing serious long-term complications. For example, if Lyme disease is not treated, the infection can spread and an individual may start experiencing problems with their joints, heart and nervous system.

“Knowing the location of potential risk areas for ticks and their pathogens remains a very important step. However, certain pathogens may have spread to unidentified risk areas, as we found in our study in southeastern Quebec,” says Crandall. She emphasizes the importance of preventative steps that can be taken on an individual level, such as using tick repellent or checking your body for ticks after being outdoors, to minimize the risk of infection.

Protecting yourself from tick bites

According to the Public Health Agency of Canada, individuals can reduce their risk of being bitten by ticks by wearing light-coloured long-sleeved shirts and pants, tucking shirts into pants, tucking pants into socks, wearing closed-toe shoes, and using bug spray with DEET or Icaridin. These steps minimize the amount of exposed skin and make it easier to see ticks. Since ticks typically live in and near areas with trees, shrubs, tall grass and leaf piles, the agency recommends that individuals walk on cleared paths or walkways, then shower and check their bodies and pets for ticks after being outdoors.

Conclusion

Climate change is expanding the geographic range of ticks and tick-borne pathogens. This will inevitably lead to an increase in tick-borne illnesses in people. Clinicians and public health authorities must keep up to date on emerging tick-borne pathogens and make sure that they test for the full range of possible infections. You can do your part by remaining informed about local tick risks in your area and taking steps to protect yourself against being bitten by ticks when you go outdoors.

Feature image: Black-legged ticks, also known as deer ticks, can transmit pathogens that cause Lyme disease and other tick-borne illnesses to people. Image: Erik Karits on Pixabay, CC0.

One thought on “Tick talk: tick-borne pathogens in Canada”

Comments are closed.