Ainslie Butler and Lindsay Jolivet, Health, Medicine & Veterinary Science co-editors

The mosquitoes that carry Zika virus are unlikely to settle in cooler Canadian climates anytime soon. But recent evidence suggests that climate change may change that in the long term.

The odds of getting Zika virus – which has been linked to microcephaly in unborn babies and Guillain-Barré Syndrome in infected adults – are very low in Canada, according to the Public Health Agency of Canada. That’s mainly because the insects that carry the disease, the yellow fever mosquito, (Aedes aegypti), and, less frequently, the Asian tiger mosquito (Ae. albopictus), are not here.

The yellow fever mosquito is a tropical species. While the Asian tiger mosquito sometimes lives in temperate climates, its larvae cannot survive harsh Canadian winters. There are plenty of other species of mosquito in Canada, but the Public Health Agency of Canada suggests that these species are unlikely to be able to transmit Zika virus, due to the lack of outbreaks in other northern temperate climates.

Adult female Aedes albopictus having a meal. Photo courtesy of James Gathany, CDC. 2002. Public domain.

What about our neighbours to the south? Both of these mosquito species are already present in the U.S. In order for mosquitoes there to start carrying Zika virus, there must be a sufficient number of people infected with the virus either as a result of being bitten while travelling or by having sex with infected men. Mosquitoes that bite these infected people become carriers of the virus. They need to survive long enough to bite others. There are a number of barriers to this happening:

- Mosquitoes that bite infected people don’t always take up enough virus particles to be infectious;

- An infected person could be a mosquito’s last meal; and

- Even if an infected mosquito survives, the virus needs to pass from its stomach to its saliva to be transmitted through a bite.

The Public Health Agency of Canada recently found that the likelihood of another tropical mosquito-borne disease, chikungunya virus, arriving in Canada was very low. The reasons for this also apply to Zika: there is no suitable mosquito host, our climate is inhospitable for the virus and few people arrive in Canada infected with the disease.

Unlike our tropical neighbours to the south and in the Caribbean, Canadian and U.S. populations tend to have built environments that protect them from mosquitoes. For example, window screens and air conditioning for climate control, as opposed to open windows, create sealed environments that prevent mosquitoes from entering our homes and businesses. These types of barriers limit our chances of being bitten.

Canadian researchers have predicted there is a moderate to high risk that climate change will lead to Asian tiger mosquitoes invading British Columbia and south-eastern Canada by 2050. Eastern and central Canada are also potential new habitats. But these predictions should be viewed with caution. The researchers are quick to point out that more research is needed to determine whether air temperatures, overwintering conditions, precipitation or some combination of these is the best predictor of suitable habitats for this mosquito. A recent paper by U.K. scientists suggests that some (southern, mostly coastal) regions in Canada may be on the verge of becoming suitable habitat for the Asian tiger mosquito.

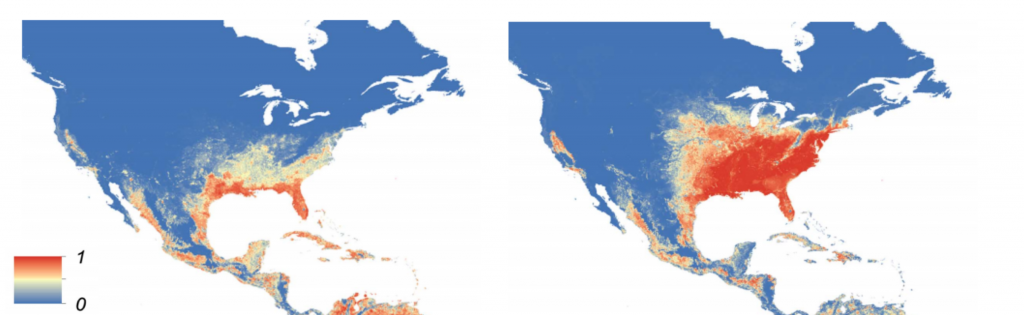

Map of the predicted distribution of Ae. aegypti (left) and Ae. albopictus (right) in North America, probability ranges from 0 (blue) to 1 (red). Images courtesy of Figures 1 and 2 in Kraemer et al., 2015. The global distribution of the arbovirus vectors Aedes aegypti and Ae. albopictus. eLife 4:e08347. Creative Commons licence CC-0. (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4493616/ )

Changes in temperature might affect how fast or how well both the mosquitoes and the virus reproduce. Changes in precipitation patterns affect where mosquitoes can lay their eggs, since they tend to breed in standing water. Scientists don’t yet know what the environmental range is for the Zika virus but it could be another potential barrier to the disease establishing itself in Canada. The malaria parasites Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax are limited by both the geographic range of their mosquito host and the suitability of the climate for the parasite itself. Like other lifeforms, pathogens do best within certain environmental conditions. When air temperatures are too hot or too cold, the replication and survival of viruses like Zika virus may be affected.

The risks of climate change to our planet and our health are becoming clearer. Zika isn’t the only virus of concern, just the newest. Researchers are also closely monitoring the spread of several viruses in the same genus, such as dengue, chikungunya, Lyme disease and West Nile. As a previous Science Borealis post on this topic points out, climate-sensitive infectious diseases may slide into new niches as climate change alters the Canadian environment. The predicted changes in Canada’s climate over the next 50 to 100 years (warmer temperatures, changes in precipitation patterns and milder winters) may open the door for mosquitoes that can carry Zika virus and other “tropical” diseases.

One thought on “Canadians don’t need to worry about mosquitoes carrying Zika – for now”

Comments are closed.