By Lindsay Jolivet & Ainslie Butler, Health, Medicine, & Veterinary Science Editors

ParticipACTION’s physical activity report card calls on governments, parents, schools and communities to drive change.

Canadian kids are failing playtime.

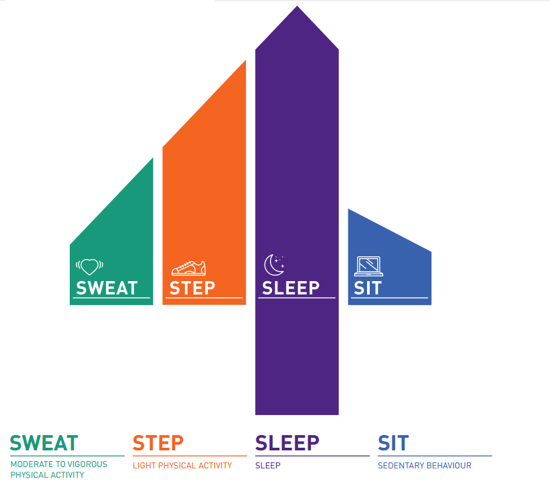

The world’s first 24-hour movement guidelines for children and youth focus on a healthy balance of activity and sleep. (Image: ParticipACTION, used with permission)

Sedentary behaviour earned Canada an F grade from ParticipACTION in its most recent report card on physical activity for children and youth. The report showed that 90% of 11- to 15-year-olds were spending more than the recommended two hours a day staring at screens.

The grade for overall physical activity was D-, with preschoolers the most likely to get their recommended daily dose of running around. The report also assessed sleep for the first time, finding that kids are sleeping less in recent years. Related news coverage detailed a “creeping sleepidemic,” whereby screen time delays bedtime, reducing kids’ sleep and the energy they have to get active the following day.

This lack of physical activity matters because overweight kids often become overweight adults, leading to increased risks for chronic conditions such as heart disease and Type 2 diabetes. In fact, more and more children are developing Type 2 diabetes before they grow up.

Screens are not the only culprit contributing to the obesity epidemic in kids, parallel to the complex pathways affecting adult lifestyles. The prevalence of heavily advertised, sugary, calorie-dense foods in larger portions and limited access to healthy food that is affordable for everyone are among the causes listed by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control. The 2015 IKEA Play Report found that about half of parents from 12 countries around the world were too worried about their kids’ safety to let them play outside. Some parents in the same report also cited stress as an impediment to playing with their kids.

Parents can help, but can’t be the only ones responsible for their children’s activity levels. (Image via Pixabay, CC0 Public Domain)

ParticipACTION delivered the bad news with a first step toward a solution: the world’s first 24-hour movement guidelines for children and youth. These guidelines focus on maintaining a healthy balance between sweat (moderate-to-vigorous activity), step (light activity), sit (sedentary behaviour), and sleep. Science Borealis member Travis Saunders and colleagues covered the new guidelines in a series of posts on PLOS Blogs’ Obesity Panacea, including a summary of the supporting evidence showing how physical activity keeps kids healthy and why sleep really matters.

But when experts talk about long-term effects and chronic disease risk, kids don’t necessarily get it. Who should be responsible for ensuring they stay active? Families are busy, and as Saunders writes, it shouldn’t be up to parents alone.

Some Canadian schools have tried using standing desks in the classroom to reduce the time kids spend sitting during the day, and there is evidence it may help them focus. Communities hold events, build playgrounds and run campaigns as part of initiatives such as Ontario’s Healthy Kids Community Challenge. Since last fall, Quebecois doctors have been able to prescribe exercise using special prescription pads.

Evidence shows that physical activity helps keeps kids healthy. (Image via Pixabay, CCO Public Domain)

But that may not be enough. Canada’s approach for getting kids active has been piecemeal and poorly coordinated, argued a paper published in the Canadian Journal of Public Health last year. It advocated for the implementation of Active Canada 20/20, a national plan developed by ParticipACTION. This spring, a senate committee recommended the government fund the 20/20 plan, which would coordinate efforts nationwide for programming, education, policy and community design around physical activity.

Childhood obesity is a tough problem, but it is surmountable. The initial findings of France’s EPODE approach, which targets schools, families and communities to build healthy attitudes around food and activity, have been promising. Variations on this program are being adopted elsewhere.

In Canada, we have slid into a crisis with more than a decade of bad grades on active living. It’s time to start taking playtime seriously.

** Header image via Pixabay, CC0 Public Domain