Robert Gooding-Townsend and Katrina Wong, Science in Society co-editors

This year we celebrate Canada’s 150th birthday. While this is a big moment in Canadian history, it is also a big moment for Canadian science. The history of Canada is so seamlessly intertwined with developments in science and technology that the two are practically indistinguishable. The relationship is much too complicated to fit into a single blog post, so we are going to compare past and present for a few key issues. They often involve economic matters, which not only represent the impact of technology on society, but are more broadly debated and better documented.

Long-distance Infrastructure

1867: Railways were the big political construction projects of the day, literally drawing the country together. British Columbia agreed to join Canada in 1871 on the promise of a railroad joining it to the rest of the country. While several different companies tried to make the connection, it was very unprofitable and the government had to bail them out. Funding for railways consumed a quarter of the federal budget in 1875; Prime Minister John A. Macdonald was forced out of office by a scandal that revealed that the same railway companies were funding his election campaign. The promised transcontinental railroad was completed in 1885 by the Canadian Pacific Railway company and set nation development in motion.

As different branches of the railway came into operation, they facilitated the opening of mines, led to the building of iconic tourist hotels, and enabled Americans and Europeans to settle “virgin” prairie land. Still, the railways did not do well financially. Louis Riel’s Northwest Rebellion in 1885 rescued the Canadian Pacific Railway from financial disaster, when the government used its lines to move troops against the Métis and First Nations forces. At the time, the value of the CPR (at least to English Canadians) was military, not economic.

A crew laying tracks in the lower Fraser valley, 1881. The railway connection brought BC into Canada. Image: Wikimedia Commons.

2017: Today, pipelines and Alberta oil sands development plays a strikingly similar role to railways in 1867. There’s debated economic potential, political controversy, community tensions, financial wobbles, more political controversy … but now, much of the opposition is focused on human rights and environmental protection, and organized through social media. Instead of drawing the country together, pipelines are increasing division.

As with the railway, the oil sands are developed, somewhat to the detriment of indigenous people. This includes decimating wildlife populations, contaminating rivers and lakes to the point of requiring bottled water imports, and brushing aside native objections.

Communication

1867: With the railway came the telegraph, which vastly expanded communication options. This included the rise of newspapers, which were just starting to operate freely. The 1870s also saw the advent of the telephone, created by Alexander Graham Bell following his work with deaf people.

These technologies democratized access to timely information, and provided a common public knowledge base. Unsurprisingly, this brought big social changes. Newspapers wielded considerable political influence and simultaneously changed the economic and social landscape, with classified ads and less frequent letter writing. And despite its use for business, Bell himself considered the telephone an intrusion and refused to have one in his study.

2017: Today, Canadians are heavy internet users, spending more time online than any other country, despite having cellphone and wireless rates that rank among the highest in the world. While an overall internet penetration rate of 93% (in 2013) is quite high, there are multiple “digital divides”: by province, by income level, and along rural/urban splits. As video calling, online shopping, and social media continue to change commerce, language use, and social interaction, newspapers and television are struggling. While widespread access and much lower production costs could mean an even greater democratization, it may also mean we end up increasingly isolated in our own echo chambers.

Health

1867: Infectious diseases, accidents, and childbirth were among the leading causes of death. Life expectancy at birth (in 1900) was 50 years for women and 47 for men. The need for sanitation – especially for preventing cholera – was well known; it was included in Canada’s well-regarded medical education system and informed the development of municipal services. In spite of this medical education, a private healthcare system meant access to physicians was limited. Nuns, nurses, and family members (usually female) provided the rest of the health care.

Jennie Kidd Trout was Canada’s first female physician, licensed in 1875. Image: Wikimedia Commons.

2017: Life expectancy (at birth) has improved to more than 84 years for women and 80 for men. Thanks to sanitation, public safety, and widespread access to medical care, many of the historical causes of death have been eliminated or contained. The leading causes of death now are heart disease and cancer. In spite of a healthcare system that is a point of national pride, socioeconomic barriers to health remain a concern, and there are ongoing debates over drug coverage, mental health coverage, and other issues. Women now make up nearly 40% of physicians, though paid and unpaid support work remains very unequal.

Environment

1867: European colonists thought of Canada’s wilderness as unlimited, but by the mid-1880s this attitude started to change: loggers saw firsthand how rapidly the “vast expanse” of forests was shrinking. Governments and timber companies began organizing conservation and management initiatives to protect future production, such as Algonquin Park in 1893. The model of mixed economic and conservation goals was based on the earlier establishment of Banff National Park in 1885. Environmentalism was not widespread, but it was reflected in the mandate of these parks:

“The experience of older countries had everywhere shown that the wholesale and indiscriminate slaughter of forests brings a host of evils in its train.”

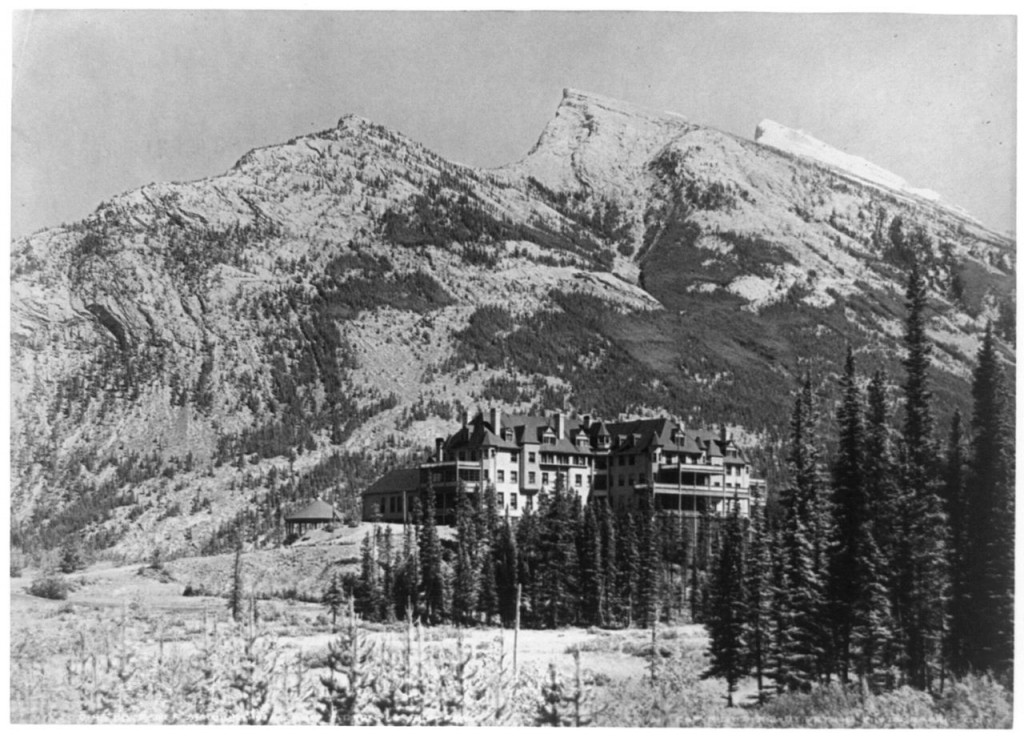

Banff Springs Hotel, 1902. A draw for tourists & sports hunters — which required a protected park. Image: Wikimedia Commons.

2017: Environmental damage has greatly expanded, as has our awareness of it. Key concerns include pollution, habitat destruction, and climate change. Some issues, such as acid rain, ozone depletion, and asbestos have been dealt with quite successfully. Others, such as habitat destruction and climate change, remain ongoing concerns. Today, these problems occupy a prominent place in the public conscious, which means that they are targets for government action — and debate. Still, the most significant change may be that environmental concerns have become part of the conversation in everything from individual diets to international diplomacy.

As we celebrate 150 years of confederation, it’s a good time to reflect on where we’ve come from. The technology we rely on and continue to innovate pushes us forward but we can still learn much from the history of our country’s development. We’re still learning how to navigate native rights for infrastructure development, how to use social media effectively, how to counter climate change… Widespread education, research and science outreach mean that scientific evidence has a greater role than it used to, though there is still work to be done. A more fundamental difference is that in 2017, Canada values diversity and contributions from historically marginalized populations. These transformations in our decision-making provide a blueprint for how we can tackle big societal challenges going forward.

*header Image: The shape of Canada, 1867. Library of Parliament of Canada.