Sri Ray-Chauduri,Technology & Engineering co-editor

With the recent safe return of another crew of astronauts from the International Space Station (ISS), what better time to consider the spacesuit: a marvel of engineering that has allowed such otherworldly pursuits.

It was 50 years ago on March 18, 1965, that Soviet cosmonaut Alexey Leonov became the first person to venture outside of a spacecraft with nothing between him and the final frontier but a spacesuit. While Leonov floated in space for 12 minutes tethered to Voskhod-2, his spacesuit drastically stiffened against the negligible pressure of space, compromising his ability to return to his ship. Realizing he was the only one who could do something about the dire circumstances, Leonov chose not to inform ground control about the situation. With the hope that he could quickly scramble back into his airlock, Leonov made the decision to depressurize his spacesuit by venting precious oxygen into the silence of space. Despite problems with re-entry and rescue – and similar high stakes drama to Apollo 13 – the crew of Voskhod-2 ultimately returned to Earth alive.

A few months later, on June 3, 1965 the United States joined the spacewalk club as Edward White became the first NASA astronaut to perform an extra-vehicular activity (EVA) in space. Although the crew of Gemini IV had to overcome issues with their cabin latch, White was able to navigate around his spacecraft for 23 minutes with his tether and a small hand-held propulsion unit using pressurized oxygen.

These first few minutes of floating in space were extraordinary achievements, as without the protection of a well-engineered spacesuit a human being would likely lose consciousness within 15 seconds. Although a variety of spacesuit models have been worn into space since 1965, the familiar white suits commonly worn by astronauts during recent EVAs include NASA’s updated extravehicular mobility unit (EMU) and the Russian Space Program’s Orlan suit.

To ensure survival beyond the comforts of Earth, fundamental spacesuit requirements include: (1) a supply of oxygen for breathing and a mechanism to remove expelled carbon dioxide; (2) a pressurized enclosure; (3) a system to regulate temperature, maintaing warmth but also removing excess body heat for cooling; (4) functional mobility to execute necessary physical tasks; (5) protection from ‘micrometeoroids‘ and radiation; (5) a method to consume water and/or food and collect bodily waste; and, (6) two-way communication that allows astronauts to interact with each other and ground control on Earth.

NASA’s modular EMU is engineered to support most of these functions; its portable life support system (PLSS) (which looks like a backpack on the astronaut) combines with multiple spacesuit layers such as a liquid cooling and ventilation garment (LCVG), an insulating layer, and a bladder layer, to help an astronaut breath in a pressurized environment at a comfortable temperature while remaining active. The outermost layer of the suit is a triple threat with its waterproof, bulletproof, and fire resistant properties. The suit also includes some less technologically intensive components, such as a cuff checklist that serves as spacewalk “to-do” list, and a wristlet with a small mirror to allow astronauts to read the control module on the front of their suits.

Although a safety tether connects astronauts to their spacecraft, the EMU includes a back-up safety net called the Simplified Aid for EVA Rescue (SAFER) to avoid the universal nightmare of drifting away into deep space. Positioned below the PLSS, SAFER is an emergency propulsion system powered by small nitrogen jet thrusters that help an astronaut control their position during an unforeseen event. SAFER is a smaller, more portable version of the manned manoeuvring unit (MMU) which was used for a small number of untethered EVAs, and resulted in the iconic photograph of astronaut Bruce McCandless calmly floating high above the Earth.

Mission Specialist Bruce McCandless II, is seen further away from the confines and safety of his ship than any previous astronaut has ever been (Photo from NASA, public domain).

Although the EMU has been used for over 30 years, NASA – along with private companies and universities – is working on the next generation of spacesuits (e.g., Z-series, Mark III, BioSuit, I-Suit). These suits of the future will improve existing designs, and advance functionalities that will be needed as humans plan to conduct longer and more complex activities related to the International space station (ISS), new orbiting stations, or outposts on other planets such as Mars. In particular, prototypes are being designed with improved radiation shielding, better suit pressurization options to decrease decompression sickness and optimize mobility, and the use of suitport docking mechanisms to bypass the need for airlocks.

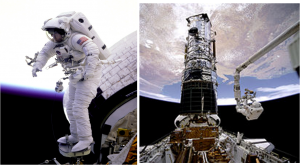

Over 300 EVAs have been carried-out since the inaugural spacewalk of 1965. They’ve been completed in support of the lunar missions, building the ISS, and repairing spacecrafts, satellites, and the Hubble telescope. They often last on the order of hours, with the longest EVA to date just shy of 9 hours. However, despite the excellent strides made in spacesuit design and engineering, there is little room for complacency. Italian astronaut Luca Parmitano, who had to end his 2013 EVA after his helmet began filling with liquid, wrote in his blog:

“Space is a harsh, inhospitable frontier and we are explorers, not colonisers. The skills of our engineers and the technology surrounding us make things appear simple when they are not, and perhaps we forget this sometimes. Better not to forget”.

Left: Mission Specialist James H. Newman conducts an in-space evaluation of the Portable Foot Restraint (PFR) which will be used operationally on the first Hubble Space Telescope (HST) servicing mission and future Shuttle missions; Right: F. Story Musgrave, anchored on the end of the Canadarm, prepares to be elevated to the top of the Hubble Space Telescope during STS-61. (public domain images)

For more information on spacesuits and spacewalks:

A riveting first-hand account of Leonovès spacewalk:

http://www.airspacemag.com/ist/?next=/space/the-nightmare-of-voskhod-2-8655378/

The evolution of NASA spacesuits:

http://www.nasa.gov/externalflash/spacesuit_gallery/index_noaccess.html

A detailed infographic on the spacesuit worn during current EVAs:

http://www.space.com/21987-how-nasa-spacesuits-work-infographic.html