Robert Gooding-Townsend, Science in Society editor

Earlier this month, Star Trek turned 50. This was a time for celebrating the show’s accomplishments and the inspiration it brought to so many. The Perimeter Institute had a particularly touching tribute with inspirational quotes, iconic architecture, and action figures. This celebration resounded across the internet with everyone from fluid dynamicists to fashionistas getting in on the fun as fans honoured the show’s influence on science, optimism, and equality. This is also an opportune time to reflect on the broader field of science fiction and the changes it has undergone since the original series aired in 1966.

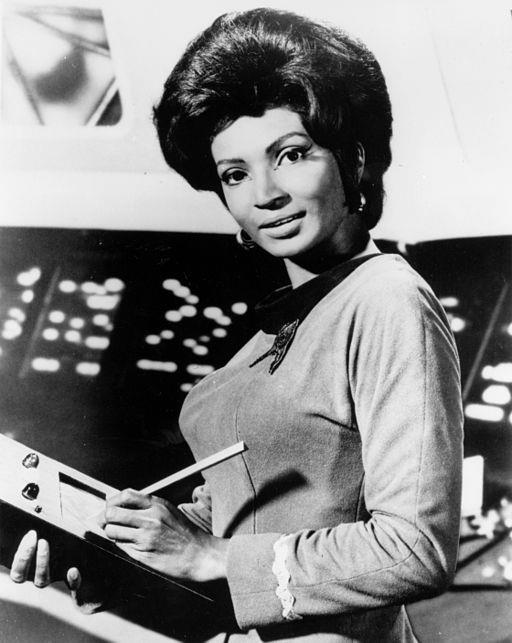

Nichelle Nichols, who played Uhura in the original series, later became a NASA recruiter. (Wikimedia Commons).

Not surprisingly, this is a topic that elicits strong opinions, often deploring the current state of affairs. Retired astronaut Stanley Love is a case in point: “Star Trek, unlike much contemporary science fiction, shows us a future worth dreaming about – and a future worth working hard to make real” (bolding mine). Similarly, it also seems unlikely that any current sci-fi will match Trek’s much-vaunted record of technological prediction. But are these opinions just the griping of disaffected fans, or do they reflect a real change in science fiction?

A full discussion of the topic would be far beyond the scope of this post. Still, there are interesting questions to think about. To explore them, I talked to some experts – Canadian science fiction writers.

James Alan Gardner agrees that Star Trek was unusually optimistic: “I’d have no problem living in the Star Trek universe. How many other futures can you say that for? I can only think of a few.” He explains this as the result of two factors: audience expectations for hour-long episodes and societal optimism.

“You always got back to a state of equilibrium by the closing credits. The structure of the show demanded that every problem be fixed in an hour. As a result, things never got too dire.

But even taking that for granted, Star Trek still was more optimistic than it was forced to be by the structure. The original [series] aired in the late 1960s, and it’s hard to describe just how optimistic things were back then. Bad times were over. The civil rights movement finally looked like it could succeed. People saying ‘no’ might stop the Vietnam War. Hippies truly thought they could change the world. We fucking landed on the moon less than ten years after we decided to give it a shot. Star Trek came out of that world: a world when almost anything seemed genuinely possible.”

Framed in these terms, it becomes almost nonsensical to lament a changing tone in science fiction. Is there really a problem with longer story arcs? And is it reasonable to saddle contemporary writers with nostalgia for a more hopeful era?

Of course, the answer to both of these questions is ‘no.’ It’s still appropriate to praise the creators of successful works and to study their personal circumstances, in addition to societal trends. But none of this analysis says much about what is actually in today’s longer, more down-to-earth stories.

Nina Munteanu, author of The Splintered Universe trilogy among other works, describes an increasing “ecological and sociological sophistication” in the genre. As an example, she cites the emerging category of ‘eco-fiction’ that includes a rich imagination of the environment, involving cooperation and responsibility rather than the flat, adversarial relationship of older “man against nature” stories.*

Lynda Williams, author of the Okal Rel series, concurs: “SF has grown up emotionally from being about wish-fulfilling technologies … to embracing the social implications of change.” This tendency is reflected in recent Hugo award winners Ancillary Justice and The Fifth Season, which explore gender, identity, and catastrophe in radically re-imagined worlds. The surge in women reading, writing, and succeeding in science fiction also reflects the changes going on in the SF landscape. Their involvement in SF would have been inconceivable at the time of the original Star Trek series.

In addition to the changing subject matter, one of the major changes in science fiction has been its expansion. There are simultaneously more works under the “Sci-Fi” umbrella and a wider acceptance by “non-genre” writers, including such works as Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow and David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas. As a Canadian example, Margaret Atwood’s writings, such as The Handmaid’s Tale and MaddAddam, highlight all of these trends: they are longer, darker works exploring feminist and environmental questions, and eschewing the label “science fiction” in favour of “science future”.

Ultimately, predicting the future will always be hard – whether in science fiction or reality. (Marshall Astor, via Wikimedia Commons).

Yes, Star Trek has done a lot for science, and for science fiction. Its success in promoting science literacy and diversity is in large part responsible for today’s diverse, scientifically literate crop of authors and audiences, as well as inspiring many scientists’ careers. Maybe technological prediction was easier in the post-war boom of the 1960’s – or maybe Trek truly was so visionary that it kick-started innovation that would not have happened otherwise. No single criterion, including optimism and accurate prediction, can directly confer excellence or success. We can look to science fiction for inspiration, warnings, and an understanding of both the times it was written in and ourselves. We can look for another 50 years of science fiction to boldly go where no one has gone before.

*Editor’s Note (9/26/2016) – For Nina’s full response to Robert’s inquiry, see her post here: “To Boldly Go Where No Human Has Gone Before…”

** Header Image: DasWortgewand, Pixabay CC0