A look at the past, the present, and the promising future of treating diabetes

Sunitha Chari, Biology & Life Science co-editor

Think of some of your favourite foods: pizza, pasta, bread – or perhaps you have a sweet tooth and enjoy desserts and chocolates. Ever wondered why these foods are so appealing? The answer is sugar, particularly glucose, which acts as our cells’ fuel. It circulates through our bodies as blood sugar and is taken up by our cells to produce energy or stored for later use.

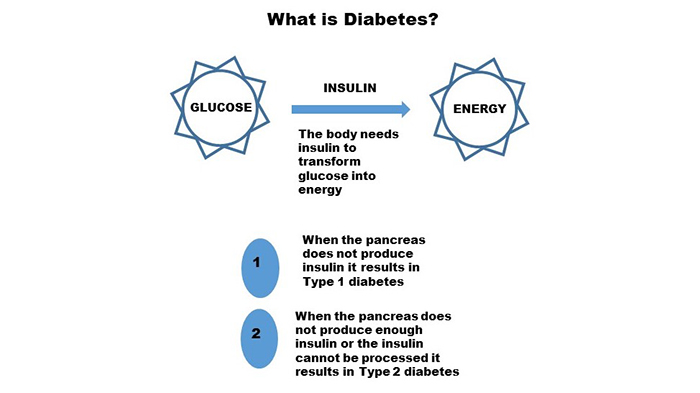

Insulin is a hormone produced by the pancreas that regulates glucose’s entry into the cells. Without insulin, glucose remains in the blood, resulting in high blood glucose levels (hyperglycemia). Excess glucose is expelled in the urine, but, over time, high blood glucose levels can give rise to a chronic condition known as diabetes. If untreated, diabetes can cause serious health complications including cardiovascular disease, blindness (diabetic retinopathy), kidney failure (diabetic nephropathy), and neurological damage (diabetic neuropathy), and can even lead to lower-limb amputations.

There are two main types of diabetes. Type 1, or juvenile-onset diabetes, is an autoimmune disorder that destroys the insulin-secreting beta cells in the islets of Langerhans of the pancreas. It affects a minority of the diabetic patient population, but is the focus of most research, since in the absence of insulin produced by the body, patients rely on daily insulin injections, and managing the symptoms requires careful monitoring of blood glucose levels.

Type 2, or adult-onset diabetes, is a more common condition caused when there is either insufficient insulin production or when the cells of the body are unable to use the insulin produced by the pancreas. In its early stages, type 2 diabetes can be managed with diet and exercise. However, if it is left unchecked and untreated, over time, patients with type 2 diabetes will require medication and/or insulin to control their symptoms.

So how did we come to our modern understanding of diabetes? The story is long, and has a strong Canadian flavour.

A long history

Diabetes was first mentioned in the Ebers Papyrus of ancient Egypt, and the first medical description was given by Greek physician Aretaeus of Cappodocia (81–133 AD). Paul Langerhans is credited with discovering the insulin-secreting structure that now bears his name in the 1860s, and, in 1889, scientists Oskar Minkowski and Joseph von Mering showed that removing a dog’s pancreas induced diabetes-like symptoms including increased thirst, appetite, and urge to urinate. But a full understanding of diabetes only emerged in the 20th century.

The Canadian connection

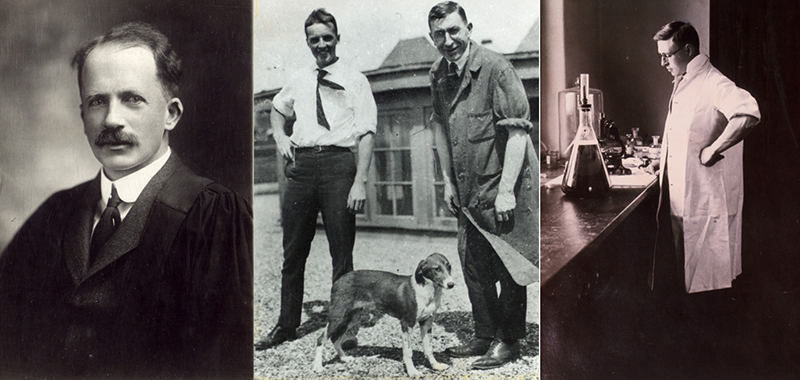

In 1921, Fredrick Banting, a surgeon, approached J.J.R. Macleod, a professor at the University of Toronto, with a plan to isolate the internal secretion of the pancreas responsible for lowering blood glucose levels. Although he was skeptical, Macleod gave Banting access to laboratory facilities, a few experimental dogs, and a student assistant, Charles Best, and let them experiment.

The Canadian team that isolated insulin and demonstrated its use in moderating type-1 diabetes: Professor J.J.R. Macleod (left), Charles Best and Fredrick Banting with a diabetic dog (centre), and James Collip in his laboratory (right). All photos: The Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, Insulin Collections

Their experiments conclusively showed that removing the pancreas induced the symptoms of diabetes, and that injecting pancreatic extract reversed these symptoms. James Bertram Collip, a biochemist, joined the group to refine the substance in the pancreatic extract, which they had dubbed “insulin”. When this refined insulin was administered to Leonard Thompson, a 14-year-old diabetic, his blood glucose levels dropped and the boy, who had been near death, rapidly regained his strength and health. A cure for diabetes had arrived, and Canada’s first Nobel Prize was awarded to Banting (who shared his portion of the prize with Charles Best) and Macleod (who shared his portion with Collip).

Always more to do

Although insulin injections control blood glucose levels, they are not as effective as properly functioning beta cells. The idea of islet cell transplantation started to gain momentum and, in 1989, Dr. Raymond Rajotte, and his group at the University of Alberta, performed Canada’s first successful islet cell transplant. But, since chronic diabetes leads to kidney failure, islet cell transplants were typically performed together with kidney transplants, which required intensive immunosuppressive regimens.

Unfortunately, this regime proved to be toxic to islet cell function and the islet cells quickly died. So, over the next 10 years, the group sought new ways to achieve long-term insulin independence. In 1998, Dr. James Shapiro joined the group and they developed a method to do solitary islet transplants using new immunosuppressive protocols. The results were a resounding success, and the procedure, known as the Edmonton Protocol, is now used worldwide.

The Islet Transplantation Group at the University of Alberta developed the Edmonton Protocol. Back row, left to right: Dr. Greg Korbutt, Dr. Ray Rajotte, Dr. Norm Kneteman, Dr. Edmond Ryan. Front row, left to right: Dr. Jonathan Lakey, Dr. James Shapiro and Dr. Garth Warnock. Photo: University of Alberta, Alberta Diabetes Institute

Despite the Edmonton Protocol’s clinical success, several challenges had to be addressed to improve widespread adoption. These included limited donor availability, the host body’s rejection of the donor cells, and the side effects of the immunosuppressive regimens that were needed to stop the host body’s immune system from attacking the new graft.

So, what if islet cells could be produced from the patient’s tissues? Dr. Timothy Kieffer and his group at the University of British Columbia think stem cells hold the key. Stem cells can develop into any type of cell in the body, and the UBC Diabetes Research Group is developing techniques to turn them into insulin secreting beta cells. Dr. Maria Cristina Nostro and her group at the University Health Network showed that when transplanted into mice affected by either type 1 or type 2 diabetes, these cells can help maintain normal blood glucose levels.

Are we at the threshold of the next breakthrough in diabetes research? Only time, and more research, will tell, but Canadian science is poised to play a leading role.

Managing diabetes in a sugary world

Science has helped save the lives of countless patients affected by diabetes. But it is important to remember that if the disease is detected early, many type 2 diabetics can manage their symptoms with a healthy diet and regular exercise. So the next time you grab that slab of chocolate, give a nod to the evolutionary urge that makes sugar so appealing, enjoy it in moderation, and commit to a healthy lifestyle.

~30~

Banner image: A schematic showing the relation between glucose and insulin and the causes for development of type 1 and type 2 diabetes

Hello, Hazel

The best people to answer that question are the folks at Alberta Health’s Health Care Insurance Branch. They can also tell you whether the Alberta government covers the cost of the treatment. Their contact info is online.

Regards,

Science Borealis

Ty will follow this up

Very thankful for the treatment of my Type 1 Diabetes but insulin is not a cure. Multiple daily injection now a pump and blood glucose checks multiple times a day now using CGM. These all cost money and much of my day thinking about my dosing and food etc….does this sound like a cure?

I have Type 1 Diabetes and I deserve a cure, or at least a better gift, from Canada.

Human insulin works immediately while the fastest acting Humane insulin works over four hours. That’s inhumane.

I am a Canadian and was diagnosed in August 1965 at the Vancouver General Hospital and was told by the doctor that I would be cured in 5 to 10 years. Poke. Poke.

I have Retinopathy, Nephropathy, Neuropathy, and more.

I am an Islet Cell Transplant Reject.

My evolutionary urge that makes sugar so appealing results in up to four subsequent hours of hyperglycemia which can cause death.

Come ‘on Canada. How much longer do I have to wait for a cure?

Hi

My name is Martina and I am from Slovakia. I ´m writting to you according my mum diagnose. She has a diabetes type 2. 2 years ago we read some article about some clinic or hospital in Canada where they know how to cure this type of diabetes. But we didn ´t save the link and since than we can not find it. My mum is 67 years old, doesn ´s speak english, so that is why i am writing to you in her name. She is still very active and energetic woman and if I could help her to improve somehow her way of life with your help we would be very soooo gratefull to you. I am sending this e mail to a few hospitals and clinic as I don ´t know which one can be „the ONE“ , hoping it will receive the right one and hoping for help and reply. Even advice or maybe contact for someone who can maybe help us it would help. We are ready to fly to Canada for treatment.

Thank you

Best regards

Martina Lengyelova

I cannot help but reply to your post on this.

Firstly. Your mom is 67, active and Vibrant.

That’s wonderful and as such we both would hate to see that change. Currently the cure is more of a hit and miss. It requires specific Anti rejection drugs that are no guarantee and likely have their own side effects.

The work on stem cell generated transplants that bypass the need for any future anti-rejection drugs is to me not only very promising but also somthing that needs the most funding so it can become a common and affordable solution.

I suggest you look at the BC researchers mentioned above and follow their progress. You may in future have the opportunity to help your mom participate in clinical trials.

Good luck and don’t dispair. Diabetes is no where near a death sentence but can definitely be a massive challenge.

I am 39 and have t2 diabetes. I have had a stroke now. I want cured. I have done everything I was told by my doctor nothing works. Is this really a cure? Or is this a promise of one. I would travel from America in Arkansas where I live to get treatment.

This is not a cure. No money to be made on healthy or dead people. Optimally people living with diabetes with stable sugars using their insulin living for many years is best for medical health community to make their money.

Diabetes can be managed only since there is not cure yet, but such information is a hope.