Kathi Unglert, Environmental and Earth Science co-editor

World Rivers Day has been celebrated on the last Sunday of September since 2005. It was initiated at the start of the United Nations’ Water for Life Decade by Canadian Mark Angelo, a river conservationist who had previously established BC Rivers Day to increase awareness of the importance of water resources.

Rivers have always played an important role in determining the locations of human settlement, providing habitats for fish, birds, and other animals, and contributing to the geological cycle. To understand these processes better, let’s take a trip down the Fraser River, which – at over 1,370 km – is the longest river in British Columbia and the 10th longest in Canada.

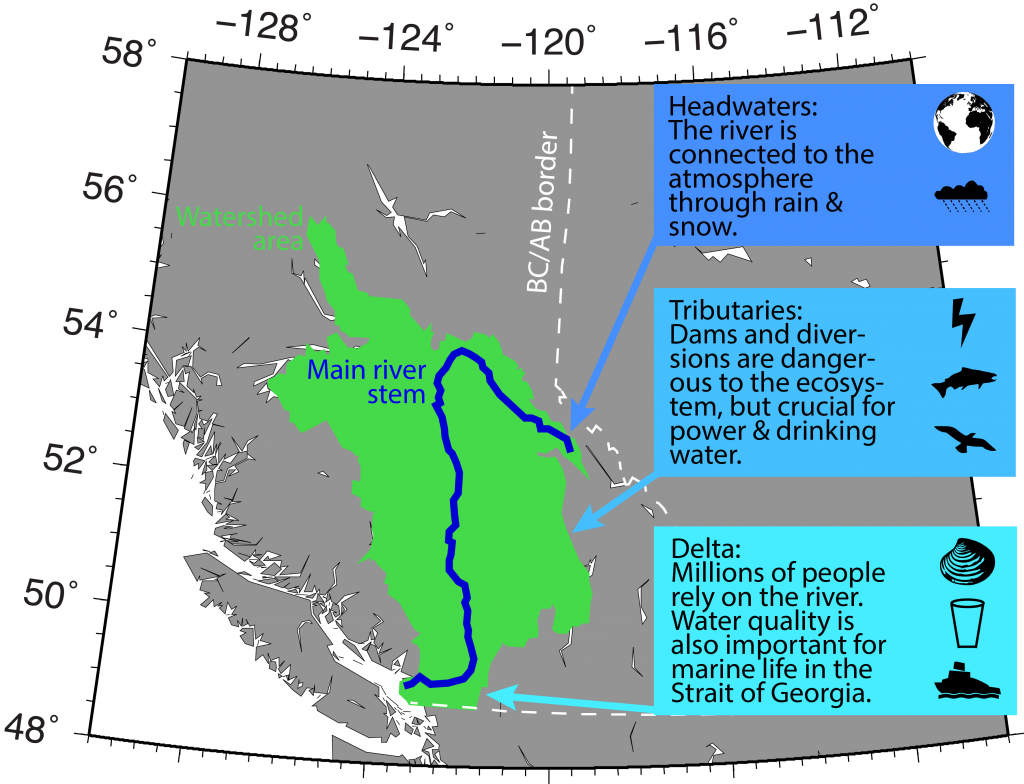

A map of southern BC/Alberta shows the approximate path of the Fraser River and outlines its watershed. The main parts of the river system are described in the blue boxes. Graphic: K. Unglert

Spring:

The Fraser River starts its journey near Fraser Pass at the BC/Alberta border. Here, what we know further downstream as a major river is nothing more than a trickle. Yet, the river constantly scours its rocky base, and carries the products of this erosion downstream. So it is that over thousands or even millions of years, mellow creeks can turn into gushing rivers in deeply incised valleys.

The health of the river ecosystems that we rely on goes hand in hand with the climate, and it starts right here at the source. Rivers are connected to the atmosphere through precipitation and air temperatures. Rising temperatures cause the snow and ice that feed the river to melt earlier and faster, leaving less water to enter the river later in the year. Low water levels in late summer bring higher than normal water temperatures, which can threaten the survival of salmon before they reach their spawning grounds. The Fraser is home to five salmon species, which are associated with 10,000 years of First Nations’ history and tradition and form the cornerstone of a $300-million fishing industry on the river – so both the ecology and economy of the river will suffer under a changing climate.

Meltwater on Athabasca Glacier, AB, near the headwaters of the Fraser River. The river is connected to the atmosphere and climate through the water collected at its source from rain, snow and ice. Image credit: Stephanie Grand

Tributaries:

The land that is drained by the creeks and streams that flow into a larger river is called a “watershed”. Man-made obstacles can disrupt the natural drainage of a watershed. For example, the Kenney Dam, built in the 1950s to power aluminum smelting just west of Prince George in central BC, diverts two thirds of the water in the Nechako sub-basin out of the Fraser River watershed and into a different watershed on the West Coast. On the one hand, waterborne organisms may suffer or die and fish migration paths may be cut off when streams are diverted or dams are constructed, leaving the rivers below them diminished or dry. On the other hand, dams are crucial for hydroelectric power and provide up to 86% of BC’s total energy supply.

Main river stem and delta:

The Fraser River watershed covers one quarter of BC (approximately the size of Great Britain), and includes half of BC’s farmland. The plains adjacent to the river are made up of millions of years of deposited sediment, which make the land fertile and ideal for farming. Unfortunately, these areas are also natural floodplains, which puts settlements and farms at risk of flooding. In turn, if fertilisers are used for agriculture along the plains, these chemicals can enter the free-flowing river and travel long distances, where they threaten salmon, the endangered white sturgeon, and other living organisms.

The Fraser River has always played an important role in the history of BC. It is an important source of drinking water, used for irrigation, a transportation route, and more. “The Descent of the Fraser River, 1808”, colour drawing by C.W. Jefferys from “Pioneers of the Pacific Coast” A Chronicle of Sea Rovers and Fur Hunters” by Agnes C. Laut, published in 1915. Source: Wikimedia Commons/Project Gutenberg

Transport of pollutants and sediment in the water varies seasonally, depending on the river flow. Ben Moore-Maley, a PhD student at the University of British Columbia (UBC), and his colleagues have found that water from the Fraser that ends up in the Strait of Georgia can change the local water chemistry and affect marine life such as shellfish. According to Dr. Mark Halverson, another UBC researcher, these changes can occur up to 40–50 km away from the river’s mouth.

A Landsat 5 satellite image of the Fraser River delta and Vancouver, 7 September 2011. The sediment that is transported by the river from the mountains into the Strait of Georgia appears as the lighter coloured, turquoise swirl (“plume”) between Vancouver and Vancouver Island. Researchers at the University of British Columbia are studying how far the plume reaches into the Strait of Georgia, and how its characteristics (pH and nutrients, for example) change during the year. These changes can have important consequences for the marine life in the area. Image credit: NASA Earth Observatory, Robert Simmon and Jesse Allen

Processes along the Fraser River occur on time scales from seconds to millions of years and the issues that come with them are diverse and difficult to tackle. It is not easy to reconcile environmental protection, geological processes, and long-term sustainability with the immediate needs of a growing population and personal convenience. For example, according to a 2010 poll of BC residents, 50–60% of respondents were strongly in favour of ensuring wildlife protection; on the other hand, less than 24% strongly supported a charge for household water to encourage responsible use.

We rely on the Fraser River for agriculture, power generation, mining, fishing, transport, tourism, and recreation. The interactions of these uses form a complex web that is difficult to untangle. Maintaining the health of our rivers while meeting the demands of growing urban centers nearby remains a challenging task and a big responsibility. The outcomes of our efforts to protect rivers will affect us, and the ecosystem, for many years to come.

*Since 1998, the Fraser River is one of 42 Canadian Heritage Rivers. Click here for more information.

** Header image: View looking east on the Fraser River, near Mission, BC. Photo: M. Lounsbery CC 3.0.