Sarah Boon, Co-founder and Management Team; Environment and Earth Sciences co-editor

By now most of us have seen the images and heard the stories: a city of over 88,000 people forced to evacuate entirely in the face of walls of flame and rising pillars of smoke. The Fort McMurray wildfire has left an entire city unmoored, with many wondering if they’ll have homes to go back to. The scene is eerily reminiscent of the Slave Lake fire of 2011, in which 7,000 people were evacuated as a wildfire burned within city limits, and the July 2015 La Ronge fire in northern Saskatchewan, which forced 13,000 people to evacuate.

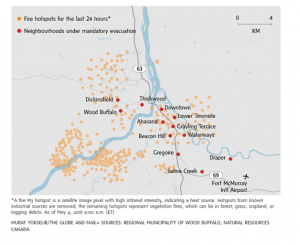

Fire hotspots in Fort McMurray (from The Globe & Mail).

The initial fire near Fort McMurray started on May 1st, the cause of which remains under investigation. The rapid fire expansion on Tuesday May 3rd was due largely to weather: temperatures reached a record high of 32°C, with high winds and an extremely low relative humidity of 15%. As of early Wednesday, May 4th, the fire had burned more than 10,000 hectares – much of within city limits. More bad news was expected today as a cold front moved through the area, bringing high winds. Read this article for more on how the fire spread.

If you’re wondering how this happened, the story lies in the conditions that led up to the initiation of this fire – the same conditions that have made much of Alberta, northern BC, and Saskatchewan highly susceptible to wildfire.

A large contributor to this year’s high fire danger was the past winter’s El Niño cycle, which was one of the strongest on record and contributed to record high temperatures worldwide. While Canada’s West Coast saw more rain and massive amounts of snow on their ski hills, the Prairies received warmer than average air temperatures and lower than average precipitation. Alberta Agriculture notes that the western part of the province on average only experiences an April this warm less than once in 50 years.

At the Fort McMurray airport, the average (1981-2010) May temperature is approximately 10°C, while daily maximum May temperatures are only in the 15°C range. This year, however, average temperatures began to reach the 15°C range several weeks early, in late April, and daily maximum temperatures regularly climbed into the mid-20s. On Tuesday, May 3rd, the Fort McMurray airport recorded a whopping maximum temperature of 32.7°C – double the normal maximum value for May.

While high temperatures have a big impact on wildfire danger, the other side of the coin is precipitation. The normal total precipitation in Fort McMurray for the months of January to April is about 70 mm. This year, the airport recorded only 41 mm from January to April – almost half the normal amount.

These dry conditions were exacerbated by a low winter snowpack. Fort McMurray is located in the Athabasca watershed. At upper elevations in the watershed, near the town of Jasper, the snowpack peaked at ~50 mm below normal, and significant melt started almost a month early (mid-April as opposed to mid-May). At lower elevations in the watershed, the snowpack was relatively thin, and melted rapidly at the end of April.

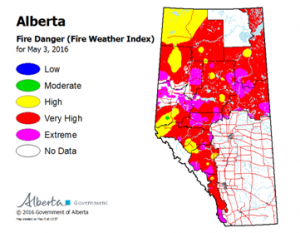

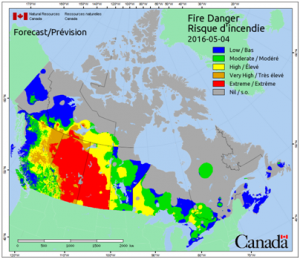

This killer combination of high air temperatures combined with low precipitation likely increased evaporation from the ground surface, drying out the forest litter layer and enhancing wildfire risk. Maps of wildfire danger from Alberta show that much of the forested area of the province is in the very high to extreme range for fire danger, while maps at the federal level show that most of Alberta and Saskatchewan, plus a section of northeastern BC, are under extreme fire danger.

Alberta fire danger (from Alberta ESRD).

National fire danger, from the Canadian Wildland Fire Information System.

The situation could still improve – as Alberta Agriculture notes, the wet (rainy) season has yet to occur in both the northern (June) and southern (May) parts of the province. However, there remains a significant moisture deficit from the overwinter period, and it’s not clear whether Alberta will receive enough rain to offset that deficit. Additionally, if temperatures continue to stay high, water loss through evaporation will continue to be a problem.

For now it’s important to remember that wildfires aren’t just about data, but about people – particularly the people evacuated from Fort McMurray. People have lost their homes, have been separated from their families and their pets, there’s a boil water advisory in place, and others are stranded on Highway 63 without fuel. If you want to help out, you can donate via the Red Cross, volunteer to help in the Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo, or provide supplies to residents who need them.

It may also be a good idea to take a moment to think about how you’re prepared for emergencies. Learn about what hazards you might encounter, put together a disaster preparedness kit, and/or volunteer with your local emergency response team. What you and your community do to prepare now will make a huge difference when disaster strikes.

11 thoughts on “Northern Alberta Wildfires”

Comments are closed.