Guest post by Catherine Doucet, MSc Biology and member of the Association of Polar Early Career Scientists (APECS)

It is mid-June, 7 am, and I slowly get out of my tent to join other members of the crew already chatting over coffee. The sun is high and bright like it will be all day, since I am above the Arctic Circle on Bylot Island, just north of Baffin Island, in Nunavut. I sit beside the “lemming guy” and just across from the “avian predator team leader” while the “plant girl” is stirring her oatmeal. Here at Camp 1, the main station for the Ecological Studies and Environmental Monitoring at Bylot Island, Sirmilik National Park, a multi-disciplinary team is exploring and quantifying the tundra of the Quarlikturvik Valley. Their research questions revolve around investigating the impacts of environmental changes on the arctic ecosystem – interactions among species, population dynamics, vegetation, geomorphology, meteorology and much more.

I am part of the “insectivorous birds team” and my attention is focused on the Lapland longspur, a small songbird. What is special about this bird? In addition to being the cutest little bundle on the tundra, it is a short-range migrant that eats arthropods, nests abundantly on Bylot Island, and has been monitored since 2005. In other words, it is an ideal model for investigating the effect of a timing mismatch between resource availability and juvenile requirements on reproductive success in the context of global warming.

The Arctic is a highly seasonal environment and the best rearing conditions are short-lived. So, it is vital to synchronize this stressful period with abundant food resources! However, the rapid changes currently occurring in the Arctic may affect species’ ability to synchronize their reproduction with the peak in food resources needed to feed their young.

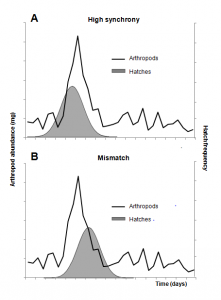

As species respond differently to environmental change, predators and their prey may shift their respective breeding periods in different ways. As a consequence, a mismatch may appear between the timing of peak prey availability and the high energetic demands of juvenile predators – such as young Lapland longspurs – which may lower overall reproductive success (see diagram).

Conceptual diagram showing the relationship between food resources and hatching dates in either a synchronous (matched) or mismatched context.

It is now 8 am and my backpack is ready for a day in the valley. My first task is to locate and monitor the nests. Patience and keen eyes are essential for finding Lapland longspur nests, as the birds are well-hidden ground nesters and the tundra is vast. Success rates are high, however, since over the years hundreds of nests have been monitored from egg-laying until the chicks take off. When a nest is found, the chicks are regularly weighed and measured so that we can keep track of their growth.

After wandering around looking for birds, I need to collect data for the other part of my equation: food! So in the late afternoon, I set off towards my pitfall traps: plastic containers buried in soil and topped by a mesh screen. These are the best way to catch crawling and low-flying insects and spiders. It might come as a surprise, but there are lots of arthropods in the High Arctic and, with periodic sampling, we can assess seasonal changes in their availability for birds.

With this information, it is possible to determine the degree of synchrony between food availability and the timing of breeding. Do chicks have access to the best food resources when they need them most? Does the total amount of food available matter for reproduction? As part of my Master’s thesis, I found only weak evidence that a mismatch with food resources affected juvenile growth, even though the number of eggs laid and chicks reared declined over the season. It seems that predation is much more important than food for explaining the variation in this bird’s reproductive success. Another story to be continued….

Of course, as is always the case in science, one answered question triggers many more. At least, lying in my sleeping bag at the end of another day of fieldwork, I can tell myself that I helped to understand a tiny part of the Bylot Island ecosystem. The “lemming guy”, the “fox team”, the “geese crew”, and many more students to come will generate new data and hypotheses and build up new science to slowly connect all the dots. After all, arctic science is all about collaboration. It is the only way to study these vast, complex, and fragile ecosystems that are constantly changing.