Guest post by Rolanda Steenweg, PhD candidate, Dalhousie University & Association of Polar Early Career Scientists (APECS) member

Celebrating Polar Week: March 14-20, 2016

A new field season

On little East Bay Island, off Southampton Island, Nunavut, biologists slumber in their cool, grey cabin. Surrounded by ice, they anticipate the spring arrival of their study species, the common eider, to its breeding colony in the East Bay Migratory Bird Sanctuary from their overwintering grounds in Greenland and Newfoundland.

It’s 2 AM; a graduate student’s alarm clock rings quietly near her ear. She gingerly crawls out of her cozy double-quilted sleeping bag and slips on her insulated rubber boots. Careful not to wake the seven others still sleeping in their bunks, she tip-toes to the other side of the crowded cabin and checks the weather station. Slightly foggy, 2°C and 5 km/h winds from the south: ideal eider banding weather. They are poised for a successful first day at the eider-banding nets.

Now it’s time for her to wake up her field mates. She picked her wake-up tunes the night before: Bruno Mars’ “Pumped Up Kicks” ought to do the trick. She plugs her tunes into the iPod dock: ‘ba dum da dum dum’ bellows from the speakers. The rest of the crew, a mix of professors, grad students, and research technicians, pop their heads up out of their bags, scurry out of their bunks (some more quickly than others) and dance while donning their warm clothes. They are ready to catch some ducks!

Benefits of collaborations and long-term data sets

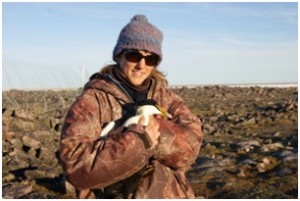

The above scene has been replayed every summer for the past 15 years with various combinations of field biologists and graduate students. Along with Environment and Climate Change Canada, we work with a diverse team of researchers that has produced remarkable insights into the birds that breed in this area (see perspectives from fellow PhD students Jen Provencher and Lisa Kennedy). Unlike most studies of birds, we are able to capture the eiders as they arrive at their breeding grounds, before they lay their eggs and begin incubation. I love having the opportunity to live on East Bay Island from late May to early July to study the eiders during this critical time. One of the best ways to learn about a species is to observe its behaviours first hand, whether at its breeding sites, as it forages, or during other periods of its lifecycle.

Working in the near 24-hour daylight of the Arctic, summer presents its own unique challenge. As enthusiastic researchers, we are tempted to work all hours to collect as much information as possible. We have to remind ourselves to get some sleep even though it’s still light outside.

Fellow PhD student Holly Hennin and I were both curious about how the eiders have adapted to the long Arctic summer days. Animals at lower latitudes are typically limited by periods of darkness, so they primarily forage during the day. Given that eiders in the north are not limited by darkness, do they forage around the clock?

To answer this question, we measured a hormone called corticosterone. This hormone is thought to be regulated by the adrenal gland. When light hits the eye it relays a message to the brain and then to the adrenal gland. The adrenal gland then secretes corticosterone, which is an “energizing” hormone – it is what makes vertebrates get up and move! So, we looked at corticosterone levels found in female eiders’ blood collected before they lay their eggs. These samples were collected at all hours of the day, and over many years.

We found that in this population, the corticosterone level in female eiders’ blood does not change with time-of-day. It appears that the female eiders are taking advantage of the continuous daylight, trying to forage as much as possible before they lay their eggs. Common eiders are “capital income breeders”, meaning that during egg incubation they do not forage. Instead, the females, which are left to incubate alone, use up the energy they have stored as fat (considered “capital”). For their eggs to hatch, females need to have enough energy stored to last through their 25-day incubation period.

Our study shows that the time-of-day has no impact on corticosterone levels in the female eiders’ blood because of their adaptations to Arctic summer light levels. This is in contrast to other animal studies performed at lower latitudes where time-of-day needs to be accounted for in the data analysis. Without access to the long-term data set collected on East Bay Island, we would never have made this discovery.

Time to leave the island

At the close of another successful field season, the biologists board up the windows of the cabin and freight loads of gear and supplies back to the mainland via helicopter. As the days begin to shorten, they say goodbye to East Bay Island, now full of incubating eiders and brightly coloured purple saxifrage. Next year, the crew will return with new questions and new wonder to this desolate, magical place and the life that calls it home.