by Kasra Hassani & Hannah Hoag

Health, Medicine, and Veterinary Sciences editors

This is not the first Science Borealis editorial post about Ebola, nor will it be the last. We’ve discussed Ebola from multiple perspectives such as Health, Engineering, and Policy over the past few months. The deadly virus – which had previously caused only small and short outbreaks – continues to wreak havoc, with a death toll now surpassing 5,000. The virus is exotic and mysterious: we don’t fully understand how it works and we are not sure how to stop it. We don’t yet have a protective vaccine or a cure; however, supportive treatments do reduce the disease mortality rate, and a vaccine candidate has shown promise. However, despite large-scale efforts by international organizations such as Doctors Without Borders, the epidemic in Western Africa still hasn’t been controlled.

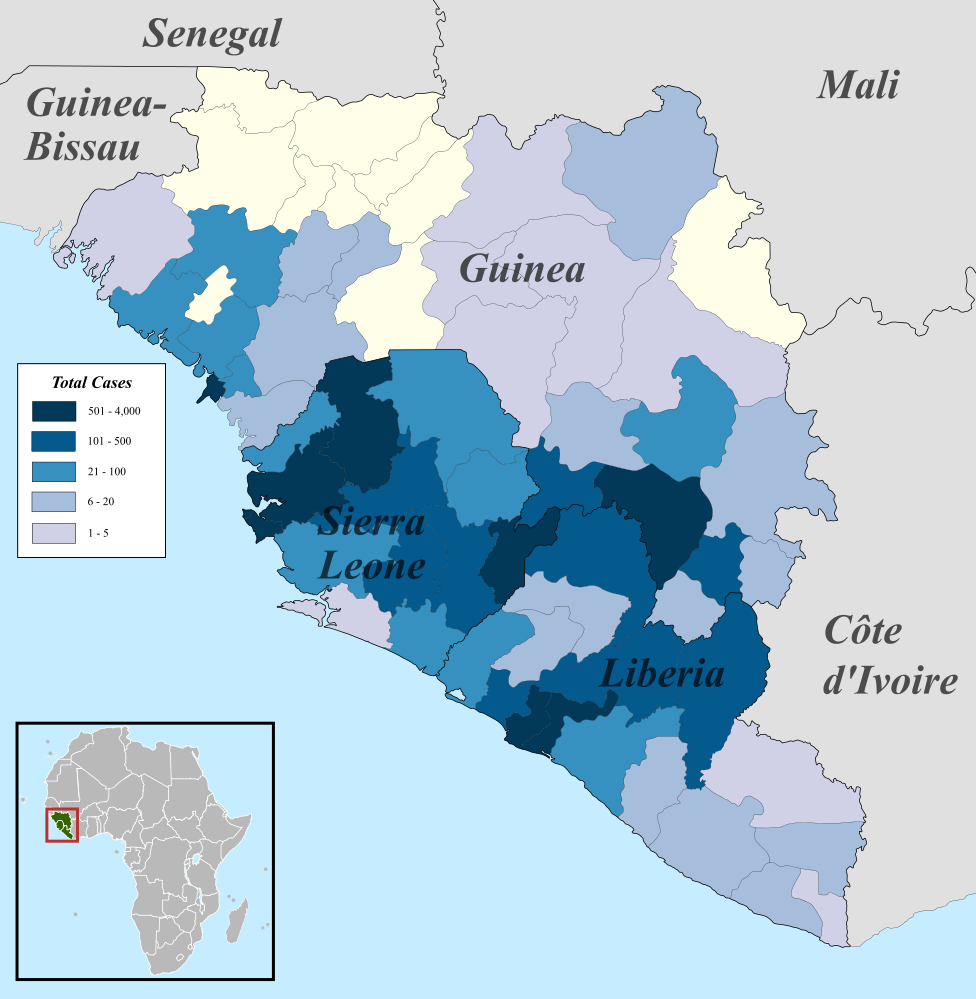

There are many reasons for our inability to control the Ebola epidemic in West Africa, but they largely have to do with the poor and vulnerable health care infrastructure of Liberia, Guinea, and Sierra Leone, the three West African countries currently experiencing the epidemic. Lack of resources and infrastructure leads both to inability to care for the sick (hence the high mortality), and inability to efficiently and accurately inform the public about the disease (hence the seemingly uncontrollable spread). All of this has caused a lot of fear, especially back in October when a few cases were identified outside of Africa. And fear doesn’t always lead to the best actions and responses. Discrimination and stigmatization, xenophobia, unnecessary travel restrictions, and pressure on public health officials and health care workers are just a few examples.

Number of cases of Ebola infection in west Africa as of November 5th, 2014. Image from WHO Ebola Response Roadmap Report. Taken from Wikimedia commons.

The perceived danger of the virus generated lots of discussion and response across society, much of it irrational and not evidence-based, even at the government level. Canada’s recent restrictions issuing visas to people who had travelled – or even planned to travel – to Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea,have been strongly criticized by public health experts and the World Health Organization (see examples here, here and here).

Irrational Ebola responses have become so widespread that they are a topic of discussion in and of themselves. Check speaking of medicine at PLoS blogs for a good read. Also check out Canadian blogger Travis Saunders at Obesity Panacea, in which he dissects two cases of how fear could irrationally alter the perception of what is important for the society, even though the evidence points elsewhere (here and here).

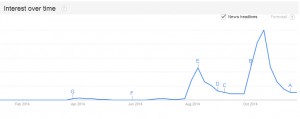

The world’s interest in Ebola peaked last month when a few cases were reported outside of Africa and has dropped since (Google search trends over the past 12 months, worldwide)

The Ebola panic has engaged the public to such an extent that scientists and health professionals must keep reminding everyone that Ebola is not a major public health issue in most countries worldwide.

In Africa, tropical diseases that kill and debilitate people by the thousands every year have been overshadowed by Ebola. Here in Canada, measles, mumps, rubella, and whooping cough are preventable infectious diseases that are far more contagious than Ebola, and are an actual threat to the health of Canadians due to low vaccination rates. With the flu season back in swing, we should be discussing the flu shot and other preventative measures.

Moving away from infectious diseases, we need a stronger focus and more effective action plans against chronic and non-communicable diseases such as heart disease, obesity, and diabetes, which are actually the major risk factors causing death and debilitation in Canada. For a more detailed discussion on why public health is not just managing infections, don’t miss University of Toronto professor Vivek Goel’s post on HealthyDebate.ca.

Yet we keep talking about Ebola. This is not to say that we should shut down all discussion on Ebola, but we need to set the facts straight and avoid succumbing to myths. We need to understand public health issues – and public health decisions – based on evidence rather than on irrational fear. And to fight against Ebola, we should send help instead of closing our borders.