Catherine Lau and Joelle Thorpe, Biology & Life Science co-editors

Like it or not, we all fall victim to celebrity clickbait. Whether we praise them or roll our eyes at their absurd behaviour, we cannot dismiss the impact that celebrities have on public opinion, especially on public health.

Celebrities can heavily influence our health-related behaviour, from what we eat, to what medical tests we undergo, to what treatments we take. But depending on what is being endorsed, celebrity influence can be good or bad for us. Children are more likely to choose food products endorsed by celebrities. And when the most popular musicians are endorsing unhealthy foods and beverages, it can counter healthy habits we want to instill in our children. On the other hand, when well-known journalist Katie Couric televised her colonoscopy in 2000, there was a 21% increase in colorectal cancer screenings by 400 American endoscopists the next month, which can be seen as a positive outcome of celebrity influence.

Using celebrity to encourage healthy behaviours could be very beneficial. When the popular tv journalist Katie Couric spoke out about colorectal cancer, this was associated with an increase in colorectal cancer screens.

However, a major problem emerges when messages endorsed by celebrities conflict with scientific evidence. For example, actor Suzanne Somers is known for advocating bioidentical hormones to reverse aging, which lacks scientific support, and proteolytic enzyme therapy for pancreatic cancer, which has been shown to be less effective than chemotherapy. Such celebrity endorsements can lead the public astray and could be harmful.

But why do we take celebrities’ advice when it is clearly not their area of expertise?

Research tells us that our trust in celebrities has a lot to do with how we perceive celebrities and ourselves. Psychological mechanisms of classical conditioning and self-conception can drive celebrity influence. A recent study showed that pairing an attractive and trustworthy celebrity with a product led to higher product ratings. Advice from celebrities that matches our own thoughts and attitudes has an even greater influence. When there is high compatibility between a celebrity and ourselves, consumers tend to purchase products endorsed by the celebrity.

Recent research has shown that popular musicians tend to endorse unhealthy beverages like pop. Shown here is an ad for diet coke, endorsed by Taylor Swift.

Delving into the brain, researchers have discovered that seeing a celebrity endorsement activates a brain region called the medial orbitofrontal cortex, which is involved in encoding positive associations. It also activates brain regions involved in explicit memories, such as facts about the associated celebrity. So, if our memories of the celebrity are positive, they can be transferred to the product or idea being promoted by that celebrity.

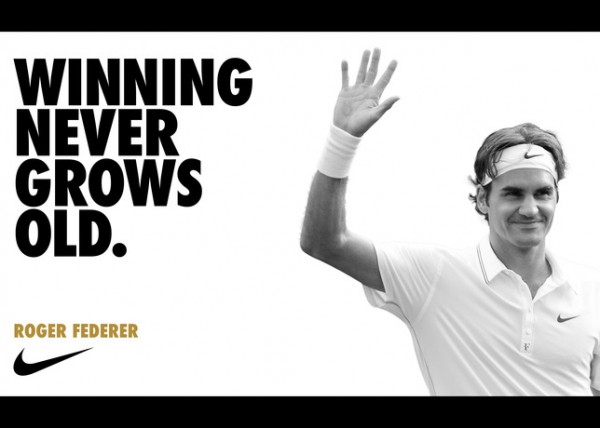

An even greater impact can be seen if we view the celebrities as “experts” (e.g., a tennis player endorsing a sport shoe). This increases the level of trust we place in them. Our recognition of a product and our intent to purchase it is increased when the product is paired with an expert celebrity compared to a non-expert celebrity. This behaviour is possibly a result of activation of the caudate nucleus, a brain region associated with trusting behaviour and processing risks and rewards.

But the perception of celebrities as “experts” can be deceiving. Television shows starring seemingly credible medical professionals, such as Dr. Oz, garner loyal fans who trust the “expert” advice offered. Although Dr. Oz has received immense criticism from the scientific community for his endorsements of miracle diet pills, his fans may disregard this and continue to follow his advice. This could be accounted for by our desire to maintain mental consistency in our beliefs and values. Anything that conflicts with our decisions, behaviours, or opinions can be uncomfortable; to avoid this discomfort, we tend to justify our actions, such as believing that celebrity advice is more credible than other sources. This can be harmful if it impedes healthy behaviours supported by the scientific community and other medical professionals. For example, using miracle diet pills could discourage people from eating healthily or exercising.

Athletes endorsing athletic brands, like Roger Federer teaming up with Nike, is common. In this case the athlete is seen as an expert because he or she uses the endorsed product in their line of work. This can be very influential on consumers.

Using celebrities to promote products and influence buyer behaviour shows no sign of stopping, particularly since celebrity endorsements are associated with increased sales. So why not use it to encourage healthy behaviours and increase scientific literacy? A recent review recommended that the medical community improve its efforts to increase the public’s understanding of health issues. One way to do this is to encourage partnerships among celebrities, governments, and research groups to broadcast the best available research-based evidence for products, treatments, and behaviours that are actually good for us.

Celebrity status can be used positively, something that has been demonstrated by a number of awareness campaigns. Bell Canada’s Let’s Talk campaign has featured testimonials from actor Howie Mandel and athlete Clara Hughes aimed at ending the stigma of mental health. Similarly, the Canadian rock band Billy Talent partnered with Kids Help Phone to promote resources for young people in times of distress. We need to keep this momentum going – there’s no reason we can’t reroute the power of celebrities into public health messages that are actually backed by scientific evidence.