Michael Ralph Limmena, Health, Medicine & Veterinary Science editor

Warning: This article contains details that some readers may find distressing

With the discovery of the potential graves of 215 Indigenous children at the former Kamloops Indian Residential School and a further 751 potential graves at the former Marieval Indian Residential School, many Canadians are horrified to learn about the tragedies that occurred on those grounds. However, for those in the Indigenous communities who were sent to residential schools, these discoveries were no surprise.

The revelations reopened wounds caused by the erasure of the cultures and systematic abuse at these institutions, a exacerbated by present-day discrimination and stigma. While most of the current generation of Indigenous peoples have not been forced to attend residential school, many still experience various racist policies, especially in the child welfare system. Consequently, many regularly face racism in their daily lives and are trying to heal from the collective trauma experienced by their relatives and ancestors.

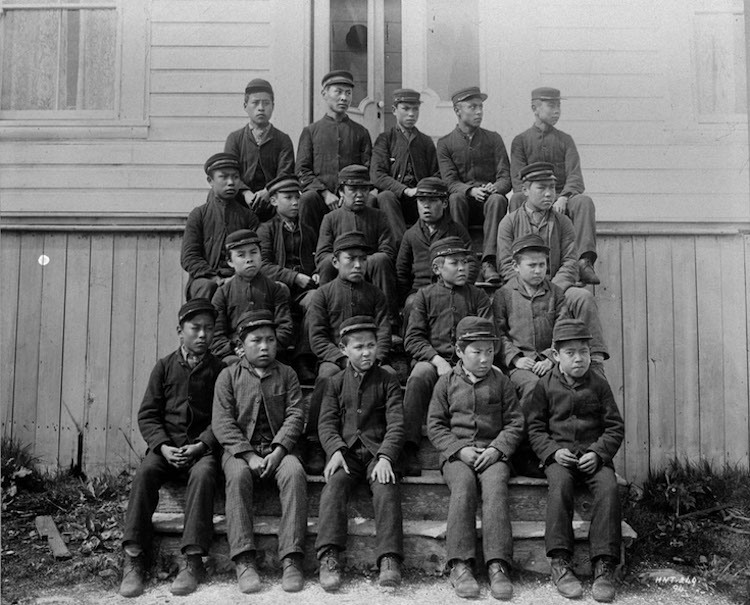

Students attending the Metlakatla Indian Residential School, British Columbia, Undated. Image source: Library and Archives Canada/Ernest Alexander Cruikshank fonds/c015037, Public Domain

A brief history of residential schools in Canada

The history of Indigenous peoples in Canada after their first contact with European settlers is tumultuous and tragic. Throughout history, Indigenous peoples have faced countless forms of abuse, discrimination, and cultural erasure. Starting in the 1880s, the Canadian government and various Christian and Catholic churches created 130 residential schools where more than 150,000 Indigenous children were forcibly separated from their parents at a young age to attend these schools.

The purposes of these schools were to eliminate Indigenous cultures and assimilate Indigenous children into Canadian society. They were forbidden to practise their cultures, including speaking their language and wearing their traditional clothes. They were often malnourished, given a poor education, and experienced physical, sexual, and psychological abuse. While many think of residential schools as something of the distant past, in reality, the last residential schools closed only in 1996. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission estimated that 4,000 to 6,000 Indigenous children died in residential schools; however, the true number may be far higher.

Unfortunately, the list of historical injustices committed against Indigenous peoples in Canada goes beyond just these policies and cannot be completely covered in this article. You can find more information about this painful part of our history through the Indigenous Foundations, Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, and many others.

What is intergenerational trauma?

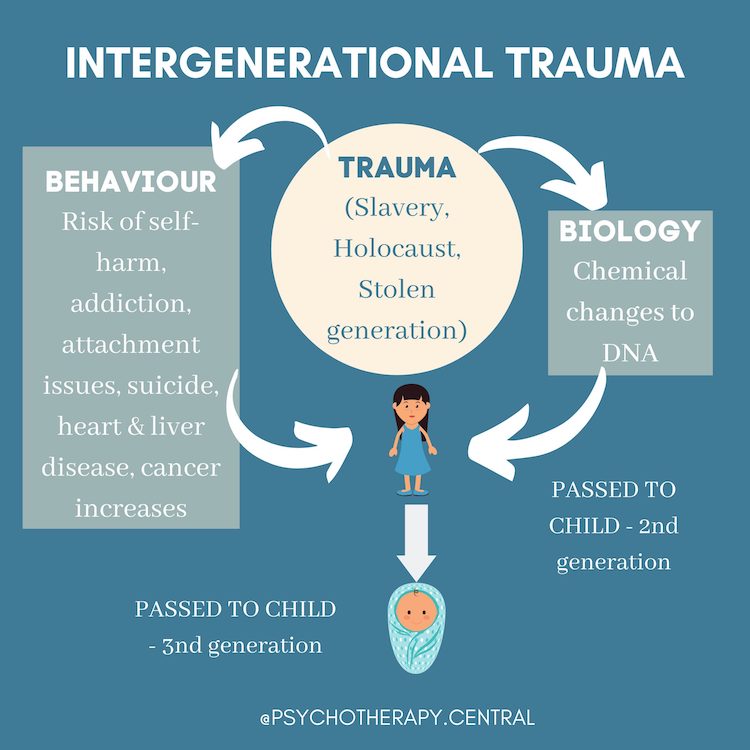

While most of these harmful policies are no longer practised, multiple generations of Indigenous communities continue to struggle with the trauma they caused. Trauma is a response to highly distressing situations, such as abuse and natural disasters, that negatively affect how a person thinks and behaves in the long run. When trauma affects future generations who didn’t experience it directly, it is known as intergenerational trauma. This kind of trauma has been documented in the children of Holocaust survivors, Rwandan genocide survivors, and victims of war, violence, and abuse. The consequences of such trauma can be devastating to subsequent generations.

What are the effects of intergenerational trauma?

Amy Bombay is an Associate Professor at Dalhousie University in Halifax and an Ojibway researcher from the Rainy River First Nations who studies intergenerational trauma in the Indigenous communities. She says that “often, the children and/or grandchildren [of residential school survivors] are at increased risk of psychological distress. What I mean by that is [that they are more prone to] symptoms of anxiety and depression [and] substance, as well as, thoughts of suicide and suicide attempts.”

She notes that these children are more likely to experience childhood adversities – events that significantly threaten a child’s physical and psychological health. These events include childhood abuse, poverty, and separation from parents – the same childhood adversities experienced in residential schools. These early-life traumas put residential school survivors at higher risk for health problems (heart disease, diabetes) and social conditions (homelessness, substance abuse). These traumas can also “impact the environment and quality of care” that survivors provide to their children.

A flowchart explaining the effects of intergenerational trauma and how it is transmitted. Image by Jennifer Nurick. Used with permission.

How are these traumas passed on to the next generation?

Intergenerational trauma passes to subsequent generations in many ways. As already mentioned, traumatized people may provide less than optimal care to their children, transmitting the hurt to the next generation. Severe intergenerational trauma can affect subsequent generations at the genetic level.

One of the most widely researched but highly debated is the epigenetic pathway. Epigenetics examines how our behaviour and environment affect our genes and how these changes are “passed on” to our children. Genes control traits such as our eye and hair colour. They also affect our risk for some diseases, such as heart disease and some cancers. It is important to note that having a genetic risk for a specific disease does not mean one will develop the disease.

The interaction between our environment, behaviour, and disease is highly complex and operates through multiple pathways. Normally, our bodies “turn on” and “turn off” specific genes through a complex and tightly regulated process, known as gene regulation, to adapt to changes in our environment. One of the ways that our bodies do this is called DNA methylation.

DNA methylation is a process by which our bodies add a small chemical group called a methyl group to our DNA to “turn off” some genes. However, in the case of intergenerational trauma, the gene regulation becomes dysfunctional. Some researchers suggest that experiencing severe childhood adversities may cause unnecessary methylation in some genes involved in stress, disrupting the stress regulating genes, and possibly causing a dysfunctional stress response. This response may lead to our bodies becoming overly sensitive to stress (see How does stress make you sick?). However, although some studies show epigenetic changes in human beings exposed to trauma, no studies definitively show that these changes can be transmitted biologically to the next generation by the sperm or egg cells of traumatized people.

What can Canadians do to help?

Canadians can begin to break the cycle of intergenerational trauma by educating themselves about our country’s Indigenous history. Image by Oladimeji Ajegbile, CC0, Pexels licence.

There are many ways that Canadians can help break the cycle of intergenerational trauma in Indigenous communities. According to Dr. Bombay, “Educating yourselves on these issues is the first step… and using that knowledge to educate others. Fight racism when you see it… and to put more emphasis into what political parties are actually wanting to make concrete changes is important… people need to learn about residential schools and also about other aspects of colonialism, including ongoing policies that continue to perpetuate the inequities that we’ve seen for many years and that we continue to see.”

Dr. Bombay stresses the importance of ending racism. We need to stop blaming Indigenous peoples for the health inequities they experience and start helping to support the healing process.

The historical injustices against the Indigenous peoples in Canada cannot be undone. But we can all do our part to eliminate intergenerational trauma. We can start righting historical wrongs and better supporting the Indigenous communities.

~30~

Banner image: Four people grieve at the Vancouver–Kamloops Indian Residential School Memorial. So far, the potential remains of 215 Indigenous children have been found on the grounds of the former Kamloops Indian Residential School. Image by Thomas_H_foto, CC-BY-ND.