Michael Limmena, Health, Medicine, and Veterinary Science editor

Restless nights. Late night snack binges. Pounding headaches. The ticking clock screams every second, increasing my already sky-high level of irritation. I’m very stressed out.

Stress is a physiological response to a psychologically or physically challenging situation. Many Canadians are feeling stressed. In 2015, Statistics Canada surveyed 6.5 million Canadians and found that 20 per cent of the respondents between ages 18 to 34 and over 50 described most days as being ‘quite a bit stressful’ or ‘extremely stressful.’ Twenty-five per cent of the respondents 35 to 49 years old felt the same. Five years later, a survey of approximately 46,000 Canadians, found that the portion of Canadians between ages 15 to 49 years old that felt stressed had risen to 33 per cent.

Stress, especially chronic stress, can make people feel restless, irritable, agitated, and anxious. Photo by David Garrison, Pexels

Physically or psychologically challenging events in our daily lives are known as stressors and their presence and frequency vary for each person. These challenges don’t have to be life-threatening to cause stress. Everyday activities like taking care of a toddler, being late to work, or talking to a large crowd can cause stress. Contributing factors to stress include lack of personal control, life transitions (for example becoming a parent, moving to a new country or job), and uncertainty of a situation or a role (such as responsibilities in work, relationship). Uncertainty can make situations more stressful as it leads to a lower perceived sense of control.

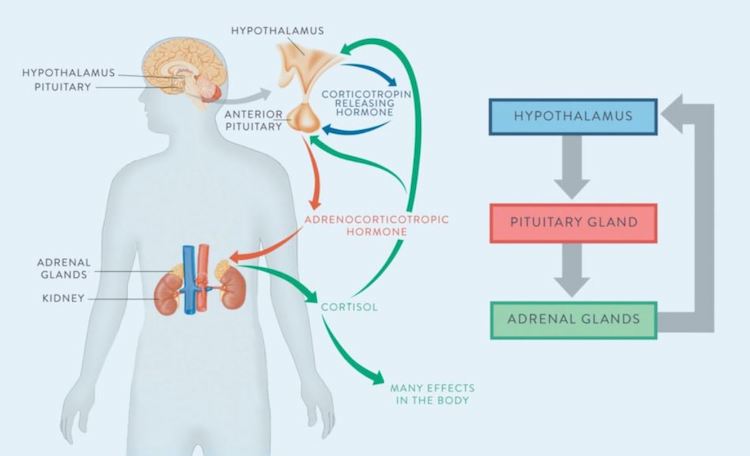

Stress triggers physiological and biochemical pathways in our bodies. One notable pathway associated with stress is the hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, a physiological network that links the nervous system with the endocrine system.

The HPA axis connects the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and adrenal gland to help the body prepare for stressful situations. Image © 2013 Dr. Sarah Ballantyne, https://www.thepaleomom.com/adrenal-fatigue-pt-1/

The pathway begins with the hypothalamus, the region of the brain that controls many involuntary functions (like heart rate, breathing, and blood pressure) and regulates hormone release. When the body experiences stress, the hypothalamus releases the neuropeptide corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) to the pituitary gland. The pituitary gland then releases adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) into the blood stream. ACTH stimulates the adrenal glands to release the hormones cortisol, adrenaline, and noradrenaline into the blood stream.

The release of adrenaline and noradrenaline activates our fight-or-flight response. This response prepares individuals to fight or flee a stressful situation and may include increased heart rate and breathing rate, decreased blood flow to non-essential organs (kidneys, intestine, etc.), and tensed muscles. The release of cortisol increases the amount of glucose in the bloodstream which provides our muscles and brain with the energy needed to implement the fight-or-flight response.

Normally, cortisol binds to glucocorticoid receptors (GCR) in the hippocampus, which shuts down the HPA axis by inhibiting the release of CRF, ACTH, and cortisol. This leads to the body returning to homeostasis and hormones returning to normal levels. However, under chronic stress, the body may adapt to the stressor in which GCRs becomes less sensitized, or resistant, to cortisol stimulation which may be detrimental to health in the long run.

In the past, the fight-or-flight response aided our survival as hunter-gatherers as we encountered various life-threatening situations. Stress was a reliable indicator of impending physical danger, so the body evolved to respond to all fight-or-flight situations. In modern times, however, where trivial daily stresses are common, the fight-or-flight response causes our bodies to overreact to stressors. For example, although speaking to a crowd doesn’t physically harm us, it still activates the fight-or-flight response, causing muscles to tense which may result in headaches and decreased blood flow to the stomach, potentially leading to stomach problems. Chronic stress results in repeated exposure to stressors which is linked to heart disease, impaired cognitive function, and other conditions. There are two potential mechanisms that contribute to these chronic effects: cortisol-induced unregulated inflammation and poor health habits.

Cortisol can strengthen or weaken our immune system depending on many factors, most notably the duration of the stressor. In response to minor, short-term stressors, cortisol affects lymphocytes (white blood cells) by increasing the concentration of pro-inflammatory cytokines, small proteins important in cell signaling, in the bloodstream. These cytokines cause lymphocytes to move to injury-prone areas and inflamed sites, promoting immune readiness, resulting in a quicker and more efficient immune response. Once the immune response is no longer needed, lymphocytes secrete anti-inflammatory cytokines which prevent the pro-inflammatory cytokines from functioning.

However, under chronic stress, repeated exposure to stressors can result in a hyperactive HPA axis, elevated cortisol levels, and GCR resistance. This resistance prevents cortisol from properly inhibiting inflammation, causing unregulated inflammation, and weakens the immune system. Research suggests that this stress-related inflammation may be associated with heart disease, depression, and other conditions.

Exercising is a common method for managing stress and produces other benefits for your body. Image by Cliff Booth, Pexels

Compared to individuals with low stress, people with high stress are more likely to engage in poor habits, such as consuming poor diets, engaging in less exercise, and smoking more cigarettes. This behaviour is a response to elevated cortisol levels caused by stress that affect the release of other hormones. These hormones can lead to the increased consumption of sweets and high fat foods.

Stress is inevitable in our lives, but there are many ways to manage stress. Seeking social support from friends and families, increasing physical activity, maintaining a healthy diet, and getting enough sleep are reliable ways of increasing resilience to stress. While non-productive coping methods (denial, avoidance, etc.) may seem to alleviate stress, they are highly detrimental in the long-term. Using productive coping methods that address the problem directly, such as reframing negative events and expressing emotions, may help sufferers cope with their stress. Lastly, seeking a licensed mental health provider or psychologist can also be helpful for managing stress.

Stress is a fact of modern life. Managing it properly is important for maintaining our health. So, take a walk, call a friend, or eat a healthy meal. Your body will thank you for it.

~30~

Banner photo by Pedro Figueras, Pexels