Louis-Martin Pilote, NCC, guest contributor

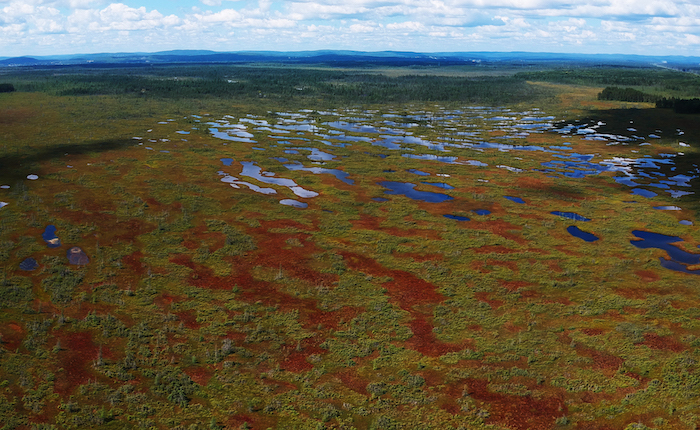

Peatlands are wetlands composed of plant residues accumulated over thousands of years. Although they are widespread in the Quebec landscape, they remain unknown to a large part of the population. However they provide us with many essential ecological services, such as water filtration and flood control. They are also valuable allies in the fight against climate change through their role in carbon capture.

As part of a research project conducted as the research chair in peatland ecosystem dynamics and climate change at the Université du Québec à Montréal, entitled “Multiproxy analysis of inception and development of the Lacâ€Ã â€laâ€Tortue peatland complex, St Lawrence Lowlands, Eastern Canada,” my objective was to reconstruct the conditions that led to the development of the largest peat complex in the St. Lawrence Lowlands – Lac-à â€laâ€Tortue – and improve our understanding of its origins. This complex is located near the municipalities of Shawinigan, Notre-Dame-du-Mont-Carmel, Saint-Narcisse and Saint-Maurice.

Evidence of the past

Peatlands are excellent ecological and climatic archives. Due to their wet, acidic conditions, there is significant accumulation of peat. Traces of plants, micro-organisms and pollen grains have been preserved in peatlands for several thousands of years. Detailed studies of these fossils allows us to reconstruct the type of vegetation or climate that existed in the past.

Carbon sinks

The ability of peatlands to store carbon in the form of peat and prevent its release into the atmosphere illustrates their essential role in the fight to reduce industrial pollution and greenhouse gas emissions. Peatlands contain more than a third of the planet’s terrestrial carbon stock (the carbon emissions absorbed by the Earth), which is a considerable amount! A better understanding of the climatic and environmental conditions that affect the development of peatlands is essential for predicting how they will respond to current and future climate change. This is especially important if we want to preserve the essential ecological services they provide us.

In the belly of the bog

Just getting around the Lac-Ã -Tortue bog was an adventure! For two consecutive summers, my team and I traversed the 66-km2 site on foot. Most of the time, rain boots proved useless as the water reached our knees. We battled voracious flies and intense heat while carrying a peat corer, a tool that helps gather soil samples. This was used to collect our precious peat cores – the peat samples that would allow us to learn more about the history of the vegetation.

What the peat reveals

We then brought our samples to the laboratory for analysis. This meticulous but exciting work can take up to two years. We precisely identified the plants that were present at the time the peatland was formed from the remains of leaves, stems or plant seeds preserved in the peat.

We were also able to determine from the analysis of a core from the deepest part of the bog that it originated from a wet depression about 10,350 years ago, just after the Champlain Sea withdrew from the region. This makes it the oldest peatland in the St. Lawrence Lowlands of Quebec. We estimated its carbon stock at about 4.73 million tonnes.

To our knowledge, this study was the first to provide an estimate of the total carbon stock contained at the scale of an entire peatland for Quebec. The study highlights the important value of wild peatlands as carbon sinks – particularly in densely populated areas where very few intact peat ecosystems remain, as most have been used for horticultural or agricultural purposes.

~30~

Louis-Martin Pilote is a research professional at the laboratoire de paléoécologie continentale de la Chaire Déclique (Geotop-UQAM) and has a master’s degree in geography. Passionate about biogeography, Louis-Martin devotes himself to the study of northern peatlands, the history of their development in association with the landscape, their role in the global climate system and their surprisingly diverse and colourful flora.

This post first appeared on Land Lines, the Nature Conservancy of Canada blog.