Stephanne Taylor, Physics & Astronomy co-editor

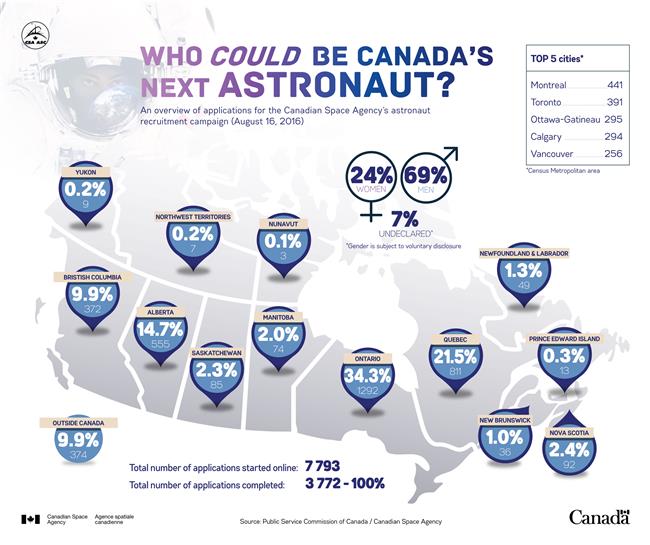

The Canadian Space Agency (CSA) is in the process of selecting its fourth class of Canadian astronauts from over 3700 applicants from across the country. Canada has been on the leading edge of aerospace engineering for decades, and Canadian astronauts and technology have played critical roles in international missions since Marc Garneau flew on the shuttle Challenger in 1984. Space exploration and missions have changed dramatically since the mid-1980’s: the shuttle program has closed, the International Space Station (ISS) has opened, more nations (including China and India) are launching rockets, and Mars is increasingly cluttered with charming robots with Twitter accounts. The European Space Agency even landed a robot on a comet!

“‘The Right Stuff’ is frequently the wrong stuff in space missions” — Ross Lockwood

The Canadian space program was started under the National Research Council, and was originally slated to be a three-year program. The program was successful, funding was extended, and Canada agreed to contribute to the ISS in 1986. The CSA was formed in 1989, and all space-related activities were gathered into a single government agency. Former Canadian astronaut Bjarni Tryggvasson notes that “[t]hese events shifted the role of the astronauts from that of payload specialists supporting Canadian science to that of mission specialists supporting space shuttle and ISS activities not necessarily related directly to Canadian activities.”

As the nature of space missions continues to evolve, the criteria the CSA uses to select astronauts have also changed. The skills and traits that make for a successful astronaut on a one-week mission are not necessarily the same ones an astronaut needs for a year or more in space. As missions become longer, and are increasingly designed with an eye towards crewed missions to Mars, understanding what makes a group of astronauts successful is critically important.

Researchers at NASA and the University of Hawai’i are studying the psychology of working in isolation in extremely close quarters at the Hawai’i Space Exploration Analog and Simulation (HI-SEAS). HI-SEAS is a base on Mauna Loa, Hawai’i, where up to six “astronauts” can live in simulated isolation. The astronauts wear a full space suit whenever they go outside the building, and communication with the rest of the world is filtered as it would be were they on Mars. Canadian Ross Lockwood participated in the four-month program at HI-SEAS, and noted that empathy and collaboration are essential when you’re confined to a small space with five other people for several months. “‘The Right Stuff’ is frequently the wrong stuff in space missions,” he joked. Seemingly unusual skills can be very useful in the confines of space: Lockwood notes that his training in scuba diving taught him how to effectively manage the safety of others in dangerous situations. Speaking languages other than English and French is also important, since astronauts now hail from all over the globe.

With the CSA backing away from at least one major robotic mission and MDA increasingly focusing on the US, the path forward for Canadian space efforts is not clear.

Astronauts have always been seen as role models but the age of social media has brought space closer to earth. On top of their scientific missions, astronauts regularly share photos and experiences about life in space with a huge audience on social media. Commander Chris Hadfield was perhaps the most prolific extraterrestrial science communicator, capturing the imagination of millions as he documented a year of life in space online. Back on the ground, Hadfield has used his profile to advocate for science, and his efforts are an excellent model for future astronauts talking about space, science, and life at the edge of exploration.

Along with changes in the role and profile of Canadian astronauts, the robotics and engineering that Canada contributes have also shifted. Canada has contributed robotic arms to the shuttle and space station programs since the early 1980’s, which made moving large payloads out of the shuttle much easier. The latest Canadian-built robotic arm is the Dextre on the ISS, which along with the Canadarm2 was made by Macdonald Dettwiler and Associates (MDA). MDA is the largest and most prominent aerospace engineering firm in Canada, and also designed and built the RADARSAT satellites, and one of the instruments on the Martian rover Curiosity. However, even after the incredible success of the Martian rover program, the CSA decided not to contribute to the rover scheduled to launch in 2020. Perhaps as a sign of the shifting priorities within the CSA, MDA recently hired a new CEO based in the US, though the firm’s headquarters remain in Richmond, BC.

The current search for astronauts is occurring only eight years after the previous one, suggesting that the CSA may be focussing on contributing personnel rather than technology to future international collaborations.

With the CSA backing away from at least one major robotic mission and MDA increasingly focussing on the US, the path forward for Canadian space efforts is not clear. Though Tryggvasson wisely says that “predicting is a risky business,” he emphasizes that Canada should have a larger role in space: “Space based sensor[s] give the most complete and comprehensive data for better understanding our Earth and the human impacts, which are real and large. Canada has been and remains a small player in this area, which we should change.”

The current search for astronauts is occurring only eight years after the previous one, suggesting that the CSA may be focussing on contributing personnel rather than technology to future international collaborations. As of the end of September, there were still about 1700 people in the pool of candidates, though that number has shrunk since then. Lockwood is still in the running, and it will likely be some months before the new astronauts are announced. Although the nature of Canadian space efforts is shifting, we are still a leading nation in space with a long history of aerospace innovation, and Canada continues to be a crucial collaborator and partner in international efforts.

Learn more about what it takes to be an astronaut and the voyage to Mars:

Generation Mars, Part 1, CBC Radio – Ideas with Paul Kennedy, broadcast on October 20, 2016

Generation Mars, Part 2, CBC Radio – Ideas with Paul Kennedy, broadcast on October 27, 2016

Destination: Mars, The Nature of Things, to be broadcast on November 3, 2016 at 8 PM