By Betty Zou, General Sciences Co-Editor

Have you ever watched The Amazing Spiderman and wondered about the physics of a man climbing vertically up a wall? Or maybe you’ve been curious about the chemistry behind homemade crystal methamphetamine as seen on Breaking Bad?

Those are the types of questions that occupy the minds of science consultants, an oft-forgotten group of people who work behind the scenes to help make movies and TV shows scientifically accurate and believable. Science consultants are typically scientists, graduate students, or others with a scientific background. Their duties range from fact-checking scripts and storylines to making sure that props and sets are realistic. Their names may not be in the end credits and they may not be paid (much), but for the scientists who advise on set it’s a fun and rewarding role that allows them to bring science to a wider audience.

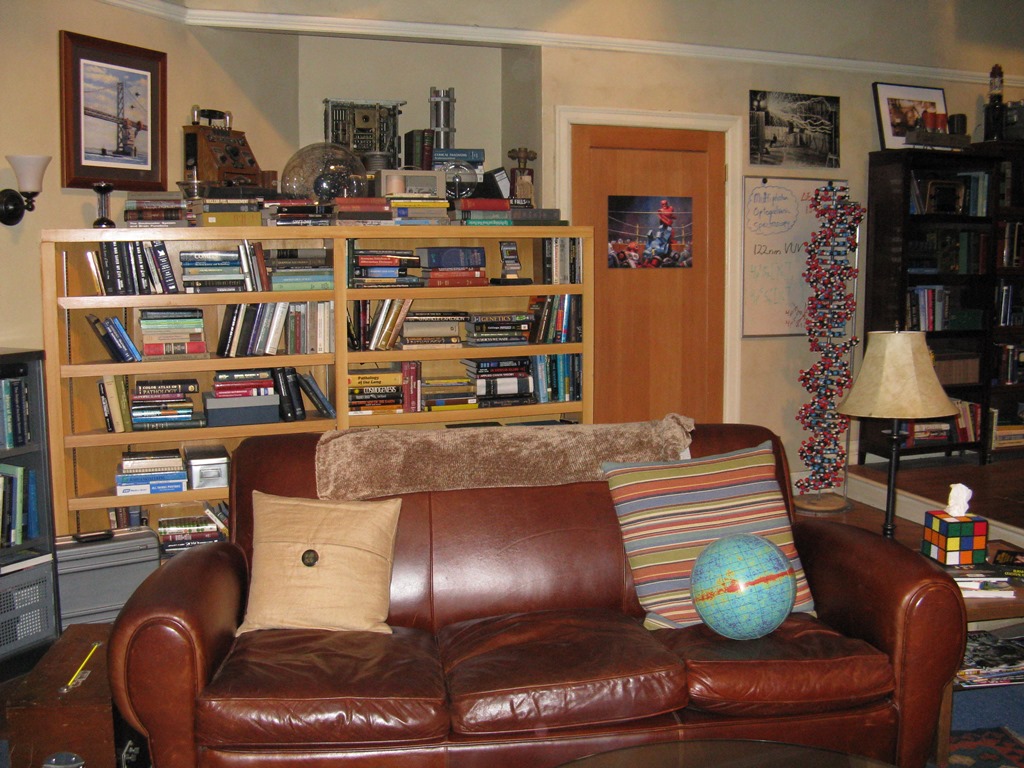

The equations featured on the whiteboards of The Big Bang Theory depict real scientific discoveries and are the work of the show’s science consultant Dr. David Saltzberg, a physics professor at the University of California, Los Angeles. Photo credit: NASA Blueshift, CC by 2.0

Science and the people who study it are, by nature, creative, imaginative, and adventurous. These three traits are also embodied in the entertainment industry that strives to create larger-than-life yet believable fantasies for its viewers. A movie or TV show’s success depends on its ability to draw people into an imaginary world and keep them there. If a story (and the science behind it) is not believable, filmmakers risk losing their audience to bad reviews and poor ratings. Despite what’s at stake, science in movies and TV shows is often distorted and overly simplified. For example, complex experiments rarely have setbacks, always finish within hours, and consistently generate easy-to-interpret results without controls.

These concerns were foremost in Dr. Aled Edwards’ mind when he agreed to serve as the scientific advisor for the award-winning Canadian TV series ReGenesis. “I said, ‘If I’m going to do this, there are conditions. The conditions are that the science has to be accurate, meaning that a polymerase chain reaction takes four hours, experiments screw up, and the lead character can’t know everything.’” The producers and writers agreed and Edwards, who had just started his new job as director of the Structural Genomics Consortium, stayed on for the entire four seasons of the show.

Each season, Edwards got together with the writers to brainstorm ideas for plotlines. “We had to come up with science ideas that were cutting edge, exciting, and that people could understand,” he says. “Everything in our show was possible. Maybe not existing, but possible.”

He acknowledges that staying true to the science can make a story more difficult to write and produce. “I had a very, very receptive producer and writers,” says Edwards. “They were committed to the real science part and that was an enormous commitment because it’s a lot harder to write when you have real world constraints on the science.”

Dr. George Charames also gives credit to directors and producers for taking initiatives to make their stories more scientifically accurate. He served as the scientific consultant for the movie Splice, a Canada-France co-production filmed in Toronto. “The reason why I’m even on set is because [the director] wanted it to be as close to being real as possible,” he says. “I think him asking me to be a part of [Splice] to make it as accurate as possible is a good testament to him and his professionalism and creative spirit.”

Dr. George Charames (second from left) on set with director Vincenzo Natali (left) and actors Adrien Brody and Sarah Polley. Photo courtesy of Dr. George Charames.

For Charames, who is now the director of the Advanced Molecular Diagnostics Laboratory at Toronto’s Mount Sinai Hospital, becoming a science consultant was a matter of being in the right place at the right time. He was a PhD student at the then-Samuel Lunenfeld Research Institute in Toronto when a group of people toured his lab. In the middle of tissue culture work, he took a break to chat with the visitors about his research. As it turns out, the visitors were members of the production team for the movie Splice, including its director Vincenzo Natali. After the tour, Charames received a call asking if he wanted to consult for the movie. He said yes and received the movie script the next day.

Charames’ responsibilities were similar to the duties of many science consultants: make the script more scientifically accurate and help the actors and writers understand the science. “The script was written 10 years prior and the science was very shaky,” he says. “We started talking about the script, making some changes [to] make it a little more believable.” He also provided a crash course in genetics to actors Sarah Polley and Adrien Brody, who starred as rogue geneticists intent on protecting the animal-human hybrid they had created. “They wanted to understand what kind of a person a geneticist is because they wanted to get into that character,” he says.

As audiences become more savvy and demanding, science consultants are increasingly being called on to bring legitimacy and realism to the screen. The benefits, though, are not just for the entertainment industry. By portraying science and scientists in a positive light, movies and television can, in turn, inspire interest and dispel myths about science.

“I just think it’s good for society to understand the limitations and the realities of how science and the scientific process works,” says Edwards. “It’s around us all the time and yet it’s ill-understood. An informed society cannot think [science] is hocus pocus.”

Maybe with the right story and people, some of that onscreen magic can be translated into real-life benefits for science.

Resources:

The Science and Entertainment Exchange: This program of the National Academy of Sciences based in the U.S. connects professionals in the entertainment industry with top scientists and engineers. If you’re interested in becoming a consultant, contact them to be added to their database. Who knows? Maybe Hollywood will come knocking on your door soon!

Lab Coats in Hollywood (MIT Press, 2011): In this book, geneticist-turned-science communicator Dr. David Kirby explores the interaction of science and cinema. Kirby is a senior lecturer in science communications studies at the University of Manchester and has studied the topic extensively.