Chantal Mustoe, Chemistry co-editor

Tap. Tap. Tap. Drip… Drip… Drip…

It’s the end of February and maple trees across the country are about to be tapped for their sweet sap. Step 1: Drill a small hole. Step 2: Insert a tap. Step 3: Gently tap the tap with a hammer. Step 4: Hang a bucket onto the tap and watch as a clear watery liquid drips into your bucket.

Collecting the sweet watery maple sap from a maple tree. Image Credit: Audubon Center of the North Woods, CC BY 2.0

This is only the beginning of the process that turns the sugary liquid in the xylem of the maple tree into the sticky goodness that we put on pancakes, waffles, fried chicken…or really anything that strikes our fancy.

But why tap trees now? Sap flow requires daytime temperatures slightly above freezing (0ºC) and nighttime temperatures just below freezing. These freeze–thaw cycles cause water in the tree to freeze and defrost, which, in turn, creates alternating positive and negative pressure in the xylem sap transport system. The appearance of leaves marks the end of the tapping season because the water now transpires through the stomata in the leaves alleviating any pressure build-up. But in the spring, when only buds cover the branches, this pressure build-up forces the sap out of the tapping hole and into our waiting buckets.

For hundreds of years, people have been harvesting the watery sap of maple trees during early spring, and indigenous names for this time of year include Maple Moon and Sap Moon. Early methods of sap harvesting used hot stones to heat the sap and the wintery temperatures to cool it. While the methods of harvesting and processing sap have changed over the centuries, two things have remained consistent, the time of harvesting and the chemistry driving the transformation of sap into maple syrup.

The first step of this transformation is the removal of up to 98 per cent of the water! Removing so much water from the sap makes the chemical process of crystallisation possible. The diversity of maple products, including sugar, syrup, butter, and snow taffy, arises from our ability to either prevent or induce this sugar crystallisation through different heating temperatures, cooling rates, and amounts of stirring.

Boiling the maple sap to increase sugar saturation. Image Credit: Audubon Center of the North Woods CC BY 2.0

For crystallisation of sugar to occur, you need a saturated sugar solution, a solution that contains the maximum possible quantity of sugar at a given temperature. A saturated solution of sugar at room temperature (23oC) is 68 per cent sugar and 83 per cent sugar at 100° C. Compare this to maple sap which is over 95 per cent water!

So where does crystallisation fit into this? The second phase of the sap’s transformation requires cooling. If you cool a hot, saturated, sugar solution while stirring it to jostle the molecules about, it suddenly becomes supersaturated, and sugar crystallises. This is how you make maple butter! The sap is boiled until the solution is saturated, then cooled slowly while stirring to encourage lots of small crystals to form. These small crystals give maple butter its unusual texture and opaqueness – like an old jar of honey that has been crystallising for years.

Millions of tiny maple crystals diffracting light gives maple butter its light opaque colour. Image Credit: necopunch CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

On the other hand, the translucence of maple syrup requires the prevention of crystallisation during the cooling phase. The sap is heated to high temperatures and then rapidly cooled with no stirring. Remove too much water and the cooling process results in maple butter instead.

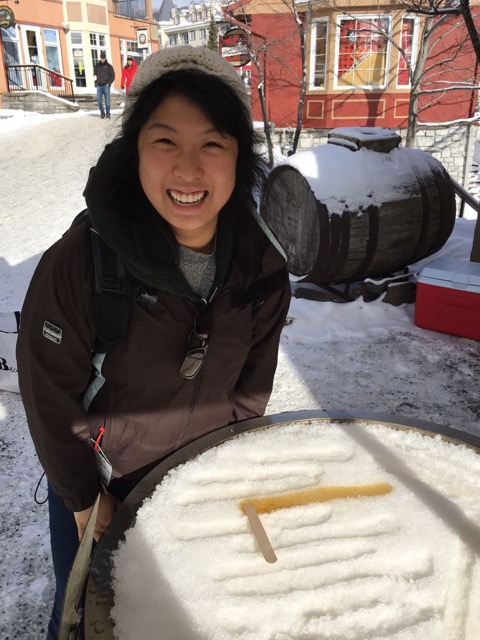

A third type of maple product, called maple taffy, has an even cooler cooling process, and not just because it’s usually done on snow. Maple taffy is chilled so rapidly, it literally becomes glass made of sugar. Glass solids, like the glass in your window or maple taffy on snow, are solids that formed so quickly that crystals didn’t have time to form.

During heating and cooling, other chemical reactions result in the different colours of maple syrup, specifically caramelisation and the lesser known Maillard reaction. Caramelisation involves heating sugars until they break down into other flavourful chemicals, and the Maillard reaction is the reason most food browns when heated. It brings the deliciousness to pizza, pan-fried dumplings, and maple syrup by recombining amino acids and sugar in the food to make hundreds of different flavourful chemicals. The different colour grades of maple syrup (light, amber, dark) result from the differing extents to which the Maillard and caramelisation reactions occur during the heating of the sap.

We can predict the extent to which the Maillard reaction will occur by the sap’s sugar content. There are three types of sugar in maple syrup: glucose, fructose and sucrose, but only fructose and glucose are involved in this reaction. Microbial processes in the tree alter the relative concentrations of these sugars by breaking sucrose into fructose and glucose. As microbial processes are faster at warmer temperatures, the sap’s sugar composition changes over the course of the tapping season. The Maillard browning of increased fructose and glucose concentrations in sap harvested late in the season gives the syrup a darker colour and stronger flavour.

The transformation of maple sap into delicious maple stickiness is a story of temperature-dependent chemical reactions. So the next time you’re cursing freezing temperatures, make yourself some maple taffy and remember: without cold weather (and some delicious chemical reactions), we wouldn’t have the delights of maple syrup!

~30~

Featured image by M. Rehemtulla – CC BY-SA 3.0