Raymond Nakamura and Liz Martin-Silverstone, Multimedia co-editors

With the hashtag PokeBlitz, Canadian entomologist Morgan Jackson used the Pokemon Go craze to encourage people to appreciate biodiversity. This inspired us to peek at other ways computer games communicate science.

Benefits

“Games are fundamental to the way we learn,” said Jeremy Friedberg, a molecular genetics PhD turned co-founder of Spongelab Interactive in Toronto, whom we spoke to on the phone.

Similarly, Katie Bedford, a former aerospace engineer who is now Production Director at NGX Interactive in Vancouver, told us by email, “The biggest benefit of using games to teach science is that it leverages our natural love of play.”

“So much can be learned from being able to fail and walk away unscathed,” Friedberg said, referring to flight simulators, but suggesting a broader application. Many of the educational games Spongelab creates include an element of simulation.

Bedford noted that well-designed games can motivate through competition with ourselves or with others. As well, she said that people who play games can learn important skills, such as “collaboration, critical thinking, decision making, and perseverance.”

Science Content

So what about games created specifically for sharing science? “Any content can be made interesting and fun,” Bedford said. And Friedberg sees games for entertainment and games for education as a continuum rather than as separate categories. Commercial games can undermine science by looking scientific without being science-based. On the other hand, educational games can be dull if they are not engaging.

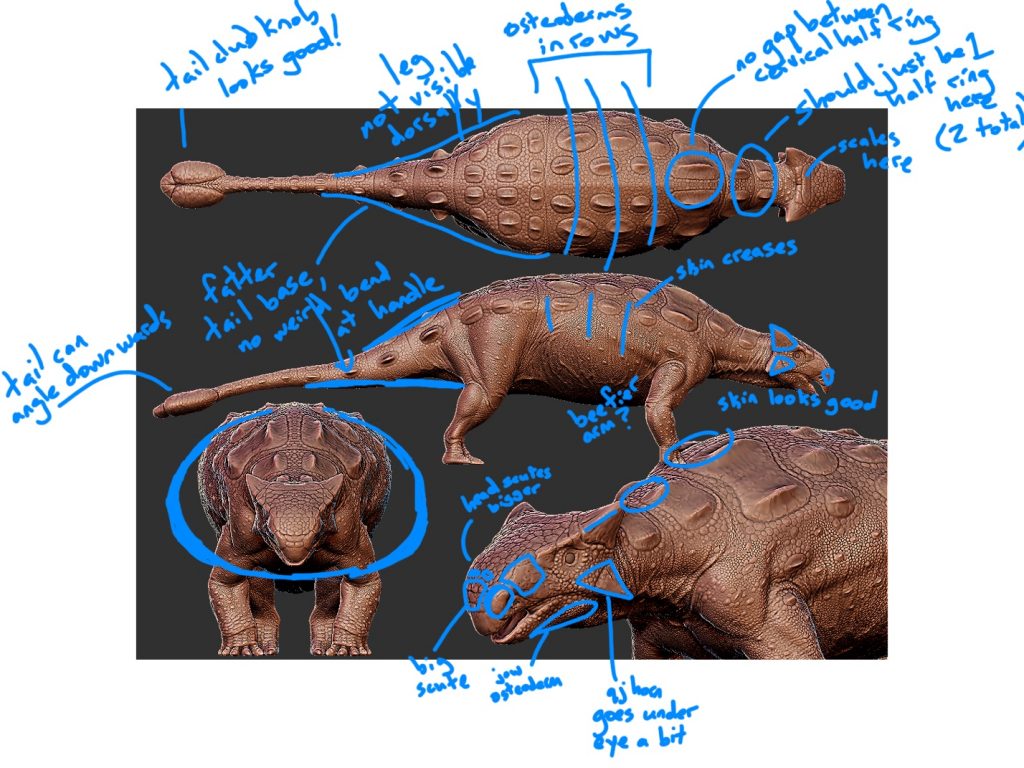

Notes from Victoria Arbour on first draft of Ankylosaurus in the game Saurian. (Used with permission)

Urvogel Games is working hard to walk the line of being fun and scientific with a dinosaur game crowdfunded through Kickstarter called Saurian. According to Victoria Arbour, a Canadian palaeontologist who consulted on the upcoming game, it is a “very naturalistic simulator of life in the Mesozoic, as opposed to a lot of dinosaur video games that involve hunting dinosaurs or dealing with the consequences of scientific experiments gone awry”. The game offers a “new perspective on the lives of dinosaurs as we understand them today”, and the team made every effort to “make the game as scientifically accurate as possible”.

Often companies work with scientists to ensure the accuracy of their games, and Arbour was asked to help with the visual rendering of two dinosaurs, Denversaurus and Ankylosaurus. She found working with Urvogel Games to be “a great collaborative experience” and that “the Saurian team was 100% willing to make changes in order to have the best model possible”, using her own research as a base.

The difference between a documentary and this kind of game is that here, people are “playing from the perspective of the dinosaur and interacting with other dinosaurs and their environment”, which allows them to learn things in a very different way than just having facts thrown at them. Players learn about dinosaurs and the Mesozoic without even realizing it.

Audience

The target audience for a computer game will determine various aspects of the design and content. NGX creates many games for science centres and other general users. Spongelab has developed many games aimed at middle and high school audiences as a way to bolster waning interest in science in these age groups. Computer games allow makers to evaluate the effectiveness of their games and this data tracking ability can allow educators to assess a student’s learning over time. Studies of Spongelab games show that they seem to appeal equally to boys and girls.

Strategies

According to Bedford, key elements of good game design include storytelling, surprises, humour, and quickly grabbing the attention of a user – which apply equally to other forms of science communication. Unique to games and other interactive media are the importance of user input, feedback, and rewards.

In places like science centres, where the game has a lot of competition for the user’s attention, Bedford said that games need a specific objective and allow users to learn something from even a short experience. In classroom settings, Friedberg said that many of the issues affecting game use have nothing to do with the game itself, but with the logistics of being part of a classroom environment. To address this, Spongelab has created a platform for organizing various kinds of digital content to make it easier for teachers to incorporate the games into their teaching.

Opportunities

Despite the many benefits of educational science games, creating them requires significant time, expertise, and financial resources. Spongelab has created a platform that allows certain game formats to be recreated with different content, so that new games do not have to be built from scratch. Another interesting model for creating games with real content are the Game Jams organized by Marianne Mader at the Royal Ontario Museum, where game developers join a festive event to compete at creating an original computer game based on museum content.

The creation of computer games is a multi-faceted art form, with a myriad of approaches, strategies, and possibilities. In this post, we’ve only played level one in exploring the ways computer games can be used to communicate science.

What has your experience been with computer games and communicating science?