By Jenna Finley, Biology and Life Sciences Editor

The first opioid overdose call I ever did was when I was a paramedic student. Lights and sirens on, we barreled into this nice suburban home to find a young man, almost as young as me, lying on the ground. The fire department had beaten us to the call and were just getting to the patient. Police were controlling the scene, and distraught family members were crying in the background. People were yelling, a dog was barking, and yet the only thing that registered to me at the time was my patient. I’d seen sick people before, but if I hadn’t felt his slowed-to-a-crawl pulse beating weakly under my fingers, I’d have thought this was a resuscitation call.

He was barely breathing, only four inhales in a minute, so I started bagging him automatically. I was also hoping to stave off the blue colouring around his lips. When we got the monitor on, his pulse was only 40 and his BP was so low I thought the machine had misread it. His family had found him 10 minutes ago.

This man was barely alive. The used needle with the dark brown-black residue told us the reason pretty quickly: heroin.

Heroin is an opiate—a naturally occurring substance derived from the opium poppy. Often this term is used interchangeably with opioid, but they’re not the same. Opioids are synthetic compounds, often stronger and more dangerous than opiates, including fentanyl, carfentanyl, oxycodone, and more. However, both opiates and opioids act on the body in the same way.

They work all over your system including the spinal cord, gut, and extremities. The drugs bind to specially named opioid receptors in your brain: mu, kappa, and delta—but they have a higher affinity for mu-type. Opioids typically work on these receptors in an inhibitory manner, often resulting in the blockage of other neurotransmitters. Basically, when these opioid molecules fall into place on their receptors, they stop other signals from going through.

This idea is the bedrock on which their pain relief rests—opioids stop pain signals from being transmitted to the brain and getting interpreted. So the impulses still exist; they just don’t make it to interpretation, so you don’t feel them. Check out the video below for a clear and concise rundown of how opioids work.

The characteristic euphoria that people can feel when on opiates is due to another effect, specifically on the “reward” centre of the brain. These opioid receptors release dopamine when their target molecules are bound to them, and that can lead to the “rush” that people feel on these drugs. Combine the pleasant high with the increased chance of drug tolerance, and addiction can follow very easily.

Now, opioids do have downsides, which is how these overdoses can be fatal. The inhibitory effects that they have on receptors don’t stop at pain. They decrease your heart rate and your blood pressure this way, but most dramatically they inhibit the respiratory centre in your brain—specifically in the pons, where your breathing rhythms are set. This induces significant and dangerous respiratory depression.

When I see an adult patient, I expect them to be breathing at a rate of 12–20 breaths per minute. That’s considered a safe range. The patient I had that day: 4 breaths in a minute. Not nearly enough to support his body. So that’s why I had to grab a bag and start violently forcing air into his lungs.

Now, I’m not trying to scare you off opioids. They are absolutely necessary for some people whose pain is refractory to any other medication. They have dramatically increased people’s quality of life and made life bearable for those who would not be able to survive without them. The doses prescribed by doctors are carefully chosen and measured to avoid those dangerous side effects. Addiction, dependence, and tolerance are where problems start.

Opioids do induce significant drug tolerance and dependence, which often leads to abuse and even overdose. Tolerance is when you need more and more of a drug to get the same effect. For example, if you take 5 mg of heroin when you’re first starting out, it won’t be long until you have to increase that dose to 6 mg, 7 mg, 8 mg, or higher to get the same effect. And because your body is so used to the drug, and used to having so much of it, you’ll have terrible side effects known as withdrawal symptoms if you try to stop.

When we first learned about opioid overdoses during our training, the instructor emphasized the lesson: “You’ll need to know this.” He was usually a light-hearted guy, always cracking jokes, but now his voice was heavy. We always listened when it was. “You will see these overdoses, over and over. Know what you’re looking for and save a life—it’s your job.” No pressure there.

An example of a naloxone nasal spray, also called Narcan. Image: VCU Capital News Service; CC BY-NC 2.0.

Then he pulled out our directives on Naloxone.

The same thing that I pulled out that day sitting on my patient’s living room floor.

Naloxone is not an antidote to opioid overdose and it isn’t very long-lasting, but it lasts long enough to save a life. Naloxone is a competitive antagonist to opioids, meaning that it also binds to opioid receptors in the body. In fact, it has a higher affinity for those receptors and binds them even tighter. However, unlike opioids, when it binds, it doesn’t do anything except keep opioids off of the receptors. And just like that, it saves your life. Suddenly, signals can get through again.

Like I said, it doesn’t last long, usually not longer than 30 minutes, but it works immediately.

We pushed 0.2 mg of Naloxone through an IV to our patient, and not even 20 seconds later he shot up on a gasp. I had to jump back to avoid us banging our foreheads together. He was already reaching for a hand to help him up, ripping the electrodes off of his body, and asking us what had just happened. Most importantly though, he was breathing well on his own. And so, suddenly, was I.

If you take only one thing away from this article, let it be this: Naloxone saves lives. If you or anyone you know takes drugs, legal or otherwise, I’m begging you to get a Naloxone kit. It’s a relatively safe drug that comes with an instruction manual. Most importantly though, it’s free and easy to find. Some paramedic services in Ontario have them specifically to hand out, but they also exist in other places for free. Here’s a list for Ontario and one for BC.

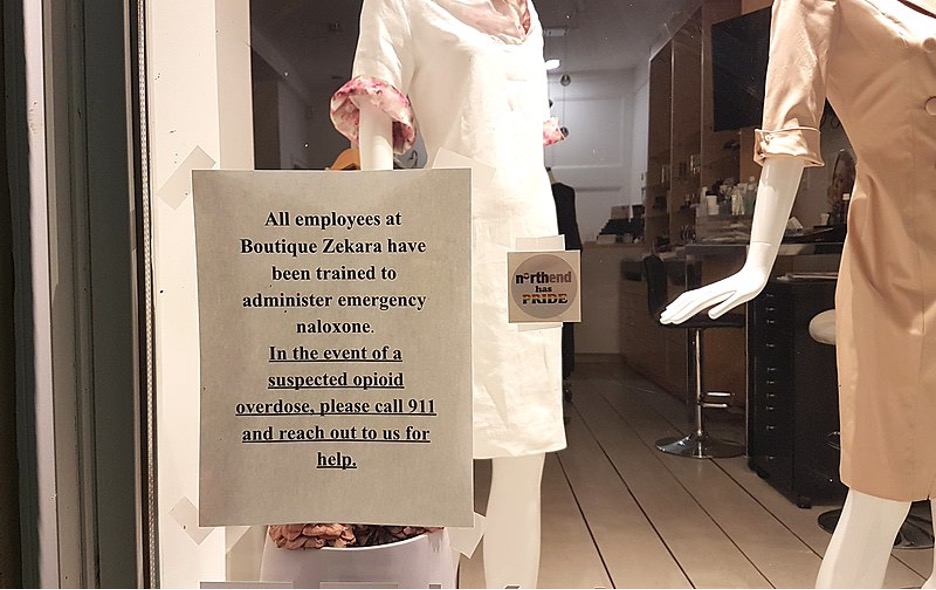

Sign in the window of a boutique in Halifax, Nova Scotia. While training is helpful, it’s not necessary for the safe use of Naloxone. Image: Coastal Elite on Wikimedia Commons.

My patient survived that day and made it to the hospital chatting with me about his dog. I was still an adrenaline-fuelled mess, so very relieved that my patient was alive. If his family hadn’t found him when they did, we would have been running a resuscitation call.

We gave his family a naloxone kit on our way out.

Please get a kit. We don’t always make it in time.

Editor’s note: This post is the first of a 2-part series by Jenna Finley about the opioid epidemic in Canada. To read Part 2, click here.

Feature image: Just a small showing of the equipment needed to respond to an opioid overdose. Image: Mat Napo on UnSplash; free to use.