By Jenna Finley, Biology and Life Sciences editor

Editor’s note: this post is the second in a two-part series by Jenna Finley on Canada’s opioid crisis. Check out Part 1 here.

The characteristics of the opioid epidemic have evolved over time. The people who take these drugs, the sources of the drugs, and even their composition have changed, making the resolution of the overdose problem a moving target.

Changing demographics of opioid drug users

The patient in my previous post was a young man in his mid-20s, who lived in a nice home and had a stable job. That’s not what most people imagine when they picture someone who overdoses on opioids—it’s not the picture featured in textbooks or the one painted by crime television shows.

At the beginning of the opioid epidemic, the average age of an opioid-related death was 44 years old for men and 52 for women. But as the epidemic has worn on, deaths have increased, and the ages of those dying have shifted. Now, those dying are much younger.

“I watched a crew bring in[to the ED] a 14 [year old] OD last week,” a paramedic in Richmond Hill, Ontario told me. “They were bagging coming in.”

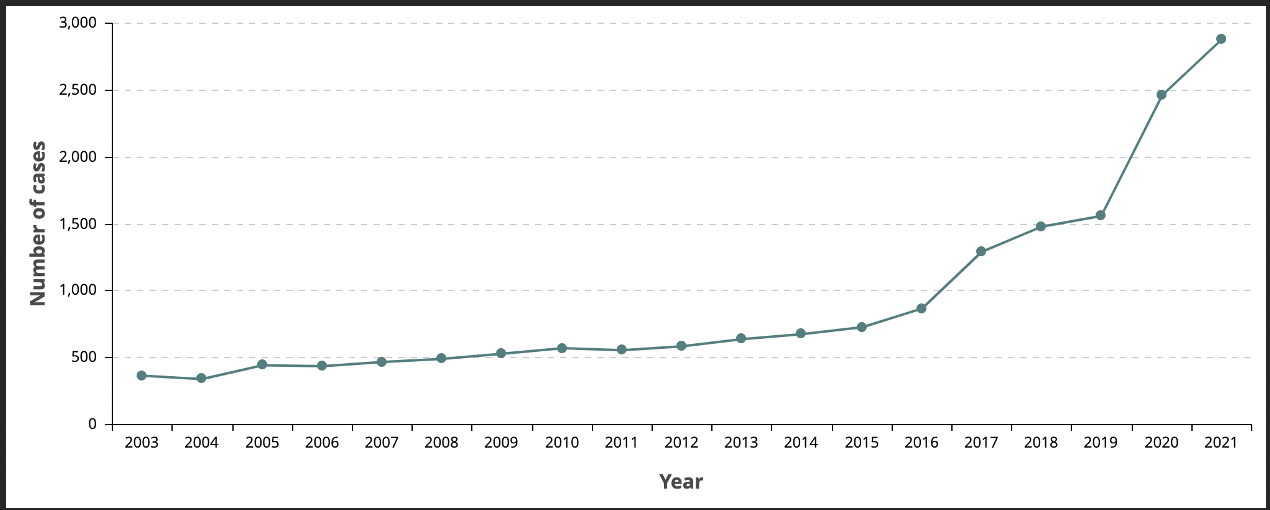

Opioid-related emergency calls are becoming more frequent. The adolescent overdose rate has shot up significantly, as the greatest increase in overdoses is in the under 35-years-old age group. And deaths have also increased. In the last five years, cases have jumped from <1000 cases to nearly 3000 per year in Ontario alone. The jump is disheartening for those of us on the frontline.

Opioid-related mortality in Ontario has skyrocketed in the last five years. Image: Public Health Ontario.

Thankfully, the Richmond Hill case had a happy ending. Thirty minutes after the paramedics arrived on site, the patient was walking around with his dad. They had administered a standard dose of nasal-spray naloxone (brand name Narcan—4 mg), an opioid antagonist that reverses the effects of opioid overdoses. At the hospital, a nurse administered a higher dose of naloxone than the paramedics had in their kit on the truck. The original Narcan dose kept him alive on the way to the hospital, where he got the extra care that ultimately saved his life.

Overprescribing opioid drugs

A lot of factors have caused this spike in opioid use and abuse. Back in the early 2000s, opioid-related deaths were mostly a result of doctors overprescribing; the pills had been marketed to the medical community as “less prone to abuse and addiction”. In essence, opioids were safe for patients to use, and it didn’t matter how much they were prescribed.

We eventually did find out that this was wrong—the drug companies had lied—but it was too late. Many people had become addicted or were on their way to addiction. Thankfully, we have ways to mitigate the damage now. Opioid prescriptions in Canada have decreased. Medical schools have expanded pain management and addiction training for students and are providing continuing education to practicing doctors. Opioid medication can also be dispensed in blister packs that help patients keep track of how much of their medication they have already taken.

Opioid-related street drugs

These are great steps, but the source of the problem has shifted. In recent years, opioid street drugs have become significantly more potent and deadly than the prescribed variety. Fentanyl is 100 times more potent than morphine; Carfentanil is 10,000 times more potent. A study in California found that since 2011, opioid overdose deaths due to prescriptions decreased by 6% while fentanyl overdoses increased by 320%. The prescription drug overdoses were mostly in older adults (>55), while the fentanyl overdoses where concentrated in younger people (<29).

The synthetic drug fentanyl is far more potent than heroin. The vial on the left contains a lethal dose of heroin; the vial on the right contains a lethal dose of fentanyl. Image: Bruce A. Taylor/NH State Police Forensic Lab.

I’ve never seen an opioid overdose due to a prescription. I talked to one colleague in Newmarket, Ontario, who had in an older patient in her 70s: “She didn’t remember she’d taken her pills already, so she took them again,” my colleague told me. When I asked what happened, she told me, “We got her back …. but [the situation] was touch and go.”

In previous years of paramedic education, that’s what we were taught opioid overdoses were like. Now we’re taught to look at everyone. “Don’t assume you won’t see an OD in a 12-year-old; it happens more than you think.” They have access to more opioid drugs now than a prescription would have gotten them before.

Increasingly, street drugs like heroin are being cut or mixed with fentanyl, causing massive problems. Drug dealers add a little bit of fentanyl to their drugs allowing them to traffic smaller amounts while maintaining the potency of the high for their customers. Sometimes, it increases the potency too much. An experienced heroin user could overdose on fentanyl without even knowing they’re taking it.

Opioids have legitimate uses

Opioids are extremely important to certain people for managing their pain. We’ve been using them to control pain since 3400 BC. They remain mainstays in palliative treatment and are also necessary for pain management when other therapies have no effect. But the increased surveillance of these drugs makes it harder for some doctors to prescribe them, even to their sickest patients.

Narcan and opioid overdoses

Narcan is a readily available form of the drug naloxone. Narcan counteracts the effects of an opioid overdose if it is administered quickly. It comes in a nasal spray that is easy to use and crucial for saving a life. Image: free to use under Unsplash License.

My service has a Narcan program, and we’re taught to give anyone on opioids a kit. My experience tells me that more paramedic services in Canada should carry Narcan kits to hand out to patients. Most pharmacies in Canada carry Narcan kits. In most places, they are free for the asking. Don’t be afraid to go and grab one – there’s no paperwork or questions involved. No training is needed, and it comes as a simple nasal spray. There are instructions in the kit if you need guidance.

But Narcan is not a miracle drug. A few weeks ago, a medic in York Region saw a 31-year-old patient. The emergency call had come in as an overdose, but it had progressed to a cardiac arrest before the medics arrived. They did everything they could to bring back the patient, but eventually had to terminate their resuscitation effort. The medic told me that someone had administered Narcan to the patient before they arrived but it had not been administered in time.

According to the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction, about 12 people die in Canada from opioid use every single day. We can do better. If you or a loved one is struggling with substance use, the Canadian Addiction Treatment Centres have compiled a list of resources for wherever you are in the country. And please, don’t be afraid to call 911—we are here to help you.

Feature image: Prescription opioids can be lethal when used incorrectly. Overprescription of these drugs was the genesis of the opioid epidemic. Photo: Istock.