Lisa Willemse and Catherine Anderson, Communication, Education & Outreach co-editors

If you’re reading this blog post, then chances are good that you’re familiar with Science Borealis. You may know that there are 100-odd blogs on this network, and that a good number of them are written by researchers or students in one of many scientific disciplines. You might think that this number is incredibly low, considering how many research institutions there are in Canada, each supporting dozens – if not hundreds – of professors, and thousands of students.

So where is all the research? Why are we not reading more about it in newspapers, on blogs, and on social media?

There are several good (and not-so-good) reasons for the relative lack of science in the mainstream, including the fact that much of it might not be ready or even sexy enough to be headline news, the not insignificant matter of muzzling of Canadian scientists, and even a lack of appetite for science stories on behalf of the Canadian public.

All of these are worthy of discussion, but our focus is on the issue of communications, particularly the fact that it is undervalued by universities and – as a result – by researchers themselves, to the detriment of science as a whole. While there are a number of excellent science communicators in Canada (some with a background in science, others with a communications background) whose primary job is to serve as a bridge between science and the public, they can only do part of the job. Who is better placed to share the intimacies and passion of science and discovery than the researchers themselves? And yet, so few do.

In order to understand why this is the case, it’s useful to look at what is expected of an academic researcher as part of their position. This can be divided into three categories of unequal weight: research, teaching and service. Of the three, research holds the most importance because it represents the greatest return on investment to the university. Research involves desk, lab, or field work, student supervision (including aspects of human resources), writing (grant applications, journal articles), and presentations at conferences or other academic events. Teaching consists of what you might expect: classroom preparation, presentations, student testing, assessment, and supervision. The third requirement, service, i.e. to your university, discipline, and – lastly – your community, falls far behind the other two in terms of importance. Depending on the institution or department the researcher is working in, service may be of lesser or greater importance and often, service within your academic sphere is all that is required.

You will no doubt have noticed that speaking to the media, public lectures (such as science cafés), writing blog posts, and monitoring a twitter feed (as well as learning how to do all these things effectively), are conspicuously absent. Most of this “superfluous” work takes place in a researcher’s spare time, assuming such a thing exists. As such it requires dedication, more than a little bit of passion, and a belief in its value.

If any of these three points is worth more discussion, it is value. There still exists, to a certain extent, a rather outdated notion that there is little value in sharing research with the public. Indeed, a common answer to the question of why researchers don’t get more involved in public communications is that they don’t get academic credit for it, and there is no career incentive to do so.

Not true. When it comes to career value, there is a steadily growing pile o’ data that shows how media interaction (including social media) can increase citation rates. Given the increasing competition for research grants, there is tremendous value in being able to communicate effectively, not just for the application itself, but in regards to factors that can influence the outcome of the award process, including citations, name recognition and who you know.

Other values, such as knowledge enhancement, expansion of research networks, and the ability to affect policy and quality of life are harder to measure, but are ably captured by Chris Buddle (here and here), and by Dawn Bazely here.

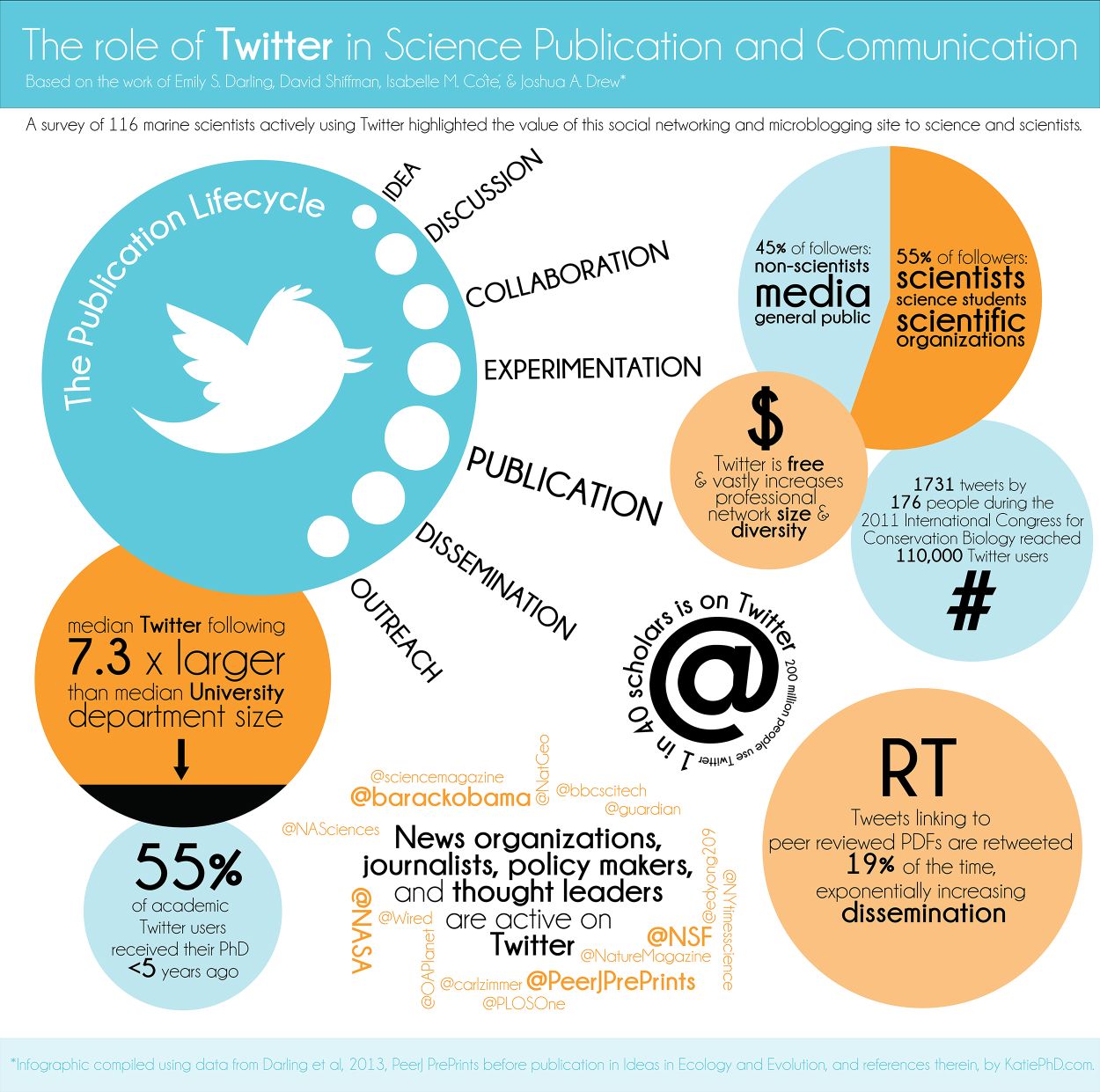

How a researcher’s engagement with mainstream and social media is viewed by his or her peers and university can also be an influencing factor. News media quickly learn whom they can count on to respond to their interview requests within deadline and with good sound bites. If you’re that person, you run the risk of being labeled a “media whore” by your peers. Spending time to develop a strong following on Twitter can be viewed as a waste of time, as a reputation-building exercise (if you have a lot of followers, it can add to your prestige and make you a thought leader), and just about anything in between. Those researchers who do understand the value of Twitter have made it one of their goals to enlighten other academics by dispelling myths and explaining the benefits.

Despite some of the challenges we’ve outlined, scientists are getting much better at embracing communications in public spheres. A handful of years ago, this blog feed would have been very sparsely populated (shameless plug: it’s growing all the time and if you are a Canadian science blogger or have a science blog in Canada, consider adding your blog to the feed). If the personal experiences of this post’s authors (one a science communicator, the other a scientist) are any indication, the increase in the number of scientists using Twitter is astounding. A 2013 study suggests that 1 in 40 scholars uses Twitter (see graphic at top) and the number of people tweeting at scientific conferences is growing steadily each year.

As more researchers begin to see the value of communications activities, either in terms of prestige or authority, in the benefits of an expanded knowledge and collaboration network, or increased citations for their published work, this upward trend of researchers as champions of their own work is bound to continue. Though it may never displace actual research, grant acquisition, or teaching in the academic setting, the ability to effectively communicate science should no longer be considered an inconsequential side pursuit by academics or the institutions in which they work.

One thought on “A little more communications on the side, please”

Comments are closed.