by Kasra Hassani

Health, Medicine & Veterinary Sciences subject editor

Animal experimentation is and will probably always remain a controversial issue. On one side stand those who believe that understanding human physiology and disease is not possible without experimenting on animals. On the other side stand those who condemn absolutely any use of animals for any purpose, scientific or other. There are people all along this polarized spectrum of opinion, leading to an ongoing discussion of the science and ethics of animal experimentation.

Last month, Teva Harrison, a Canadian artist and blogger, published a cartoon in the Walrus Magazine in which she depicted her support of animal testing for drug discovery (see the rest of her cartoons about her journey with cancer here). Teva also participated in an emotional interview on CBC 180, in which she talked about how the diagnosis of stage four breast cancer made her appreciate the benefits of animal experimentation for drug discovery and cancer therapy, despite her prior disapproval of it.

The following week, CBC 180 interviewed Alka Chandna, Senior Laboratory Oversight Specialist for People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA). When asked about her standing on the use of animals for research purposes, she reiterated PETA’s position that animals are not ours to use for any exploitive purposes, including consumption or experimentation. However, Chandna also stated:

“Scientists are increasingly recognizing that using animals in experiments to understand human disease simply doesn’t work. Animals are not reliable models for human disease.”

Unfortunately, this statement is false, regardless of where one might stand on using animals for research from a philosophical, ethical, or personal point of view.

Biological systems are complex on many different levels, which is why scientists use a myriad of models to study different aspects of these systems. For a drug study, we need to know how the drug impacts our body, including its molecules, cells, tissues, organs, and systems. ​Each of these aspects must be studied using a combination of specific models, tools, and experimental design. Some of these experiments are done in petri dishes and glass tubes or using computers, while others – especially those that study organs or entire biological systems – cannot be done without animal experimentation.​ While the individual results of each experiment don’t provide a complete picture – and even all results together still give us an incomplete picture – we need to work with the closest possible representation of reality if we are aiming to use a drug to treat human disease.

The history of science and current scientific advancements provide us with countless examples of the contribution of animal experimentation human health and animal welfare. Understanding Animal Research, a UK-based website, has gathered some of the famous ones.

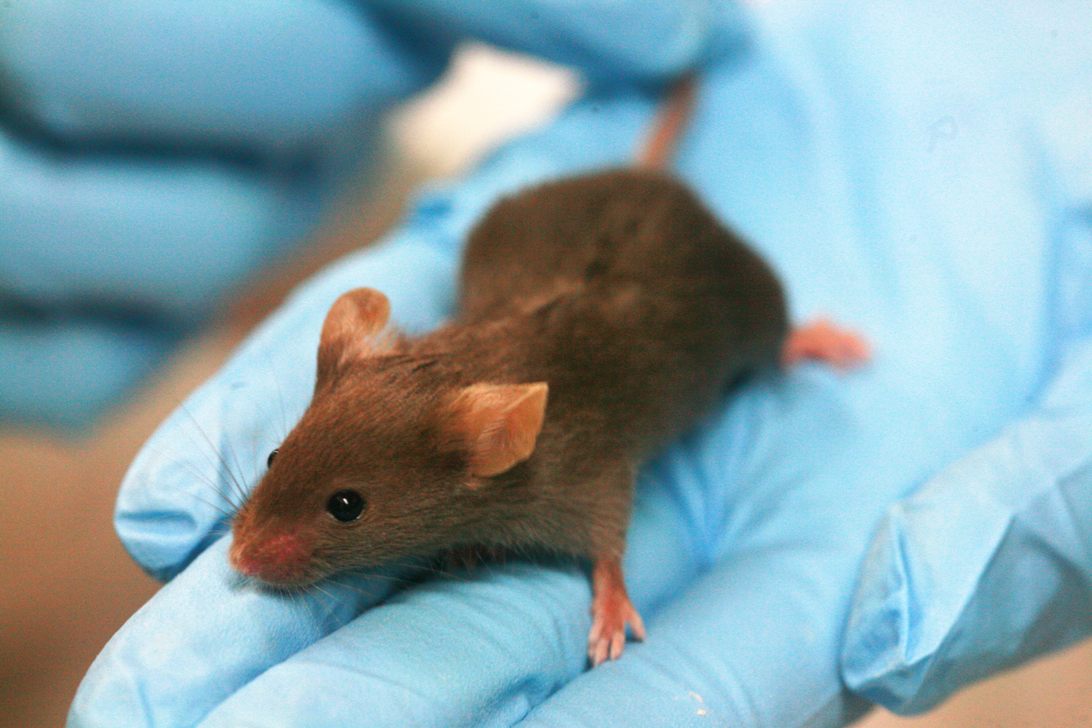

Some people claim that experimentation on animals such as mice or rats is of no use because they are too different from humans, and are thus inadequate models for human disease.

This claim is also not true. Despite many differences, all mammals have descended from a common ancestor and share most of the same genes and biological mechanisms. Even the differences between humans and animals, or within different animal groups, are interesting topics of study because they can tell us a lot about how those structural and genetic differences translate to differences in function.

British statistician George Edward Box once famously said:

“All models are wrong, but some are useful.”

It is true that, due to differences between humans and animals, many drugs that appear to be effective in animals do not show the desired impact in humans. Scientists agree that there are many limitations to animal experimentation models, and are developing alternative research methods to address these limitations. Computer models, organoids (organ-like tissues that live outside the body), microdosing, and others are among the many models that have been introduced as alternatives for animal experimentation. While these models also have their own limitations – for example, simplicity and immaturity – they remain useful, and their popularity and utility is on the rise as they continue to improve.

Will they replace animal experimentation anytime soon? No. These “alternative” models are new additions to the scientists’ toolbox, providing new perspectives on the complexities of our physiology. The more angles from which we examine something, the more complete the image that results from it.

Believe it or not, scientists will avoid animal experimentation if possible, for two main reasons. The first is that animal experiments are among the most expensive and cumbersome parts of biomedical research. And secondly, animal experimentation is governed by very strict ethics regulations that focus on either replacing animal subjects with an alternative where possible, reducing the number of animal subjects used if they are required and, finally, refining the experimentation procedure to minimize animal pain and distress.

I agree with Chandna that scientists and regulators need to work harder to find testing methods that don’t involve animals, for the welfare of the animals among many other reasons. But statements such as “animals are not reliable models for human disease” or “the animal testing industry capitalizes on the hopes and fears of medical patients and their families” are untrue or, at best, simplified representations of the reality and complexity of biomedical and pharmaceutical research.