Sri Ray-Chauduri, Technology & Engineering editor

With the holiday season just around the corner, merchants are already enticing customers with the promise of deep discounts during sales such as Black Friday. Last year, more than 90 billion dollars were injected into the Canadian economy from retail sales in November and December alone. However, with cash sales on the decline, representing only a quarter of all Canadian transactions in 2015 and predicted to fall to 10% by 2030, the majority of this business is happening via ‘plastic’ – credit and debit cards, and to a lesser extent mobile payments. But what exactly happens when a card or device is swiped, inserted, or tapped?

A card (left; image from Wikimedia Commons) and mobile device (right; Photo by Samsung Newsroom CC BY NC SA 2.0) being tapped against a card reader

Swiping a credit or debit card through a payment terminal relies on the magnetic properties of the black or silver stripe stamped on the back.The stripe is made up of tiny ferromagnetic particles and can contain up to three tracks of data, which store the information needed to complete a transaction (e.g., account number, expiry date of the card, and possibly more). The card reader passes the stripe’s information over a dedicated connection or telephone line and through a series of steps that determines whether the issuer approves or declines the transaction. Storing information on magnetic media has been around for over 100 years, and magnetic tape, like that used in cassettes or video recorders, was first developed in the late 1920s.

Modern credit cards appeared on the scene in the 1970s, thanks to engineers at IBM. The IBM team was working on new identification badges for the CIA in the 1960s when they figured out how to effectively affix durable magnetic stripes encoded with multiple tracks of data onto small plastic cards. Unfortunately, magnetic stripe technology, also called `magstripe,’ is susceptible to theft. Cards are easy to copy using a skimmer (a device attached to a real payment terminal) and, because the data on the magstripe is static, once replicated it can be used for fraudulent purposes.

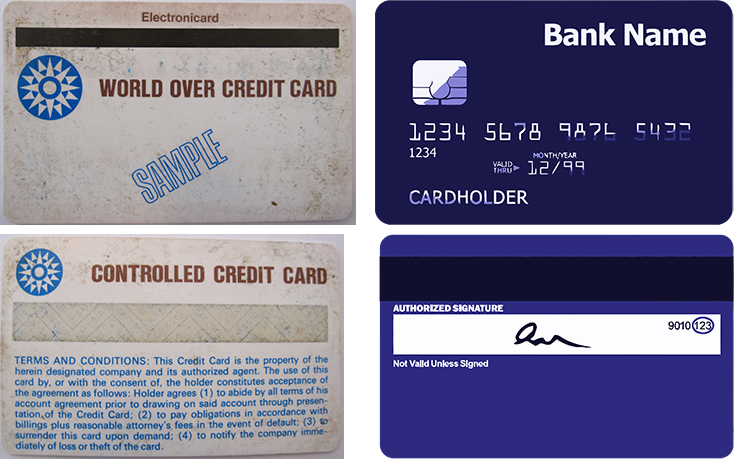

(Left; photos by Arthahn CC BY SA) Both sides of one of the first magnetic stripe credit cards; (Right; photos CC0); both sides of a current credit card with chip, stripe, and signature

A better alternative to the magstripe is the chip and personal identification number (PIN) card, or chip and signature card, also called EMV chip technology. EMV is an acronym for the three financial companies (Europay, Mastercard, and Visa) that developed the global standard for cards using microprocessors to help authenticate card transactions. EMV cards store information on a microchip embedded in the card and create a unique encrypted code for each transaction. When an EMV card is tapped instead of being inserted into the card reader, the microchip transmits information to the terminal using near field communication (NFC), a type of radio frequency identification (RFID). The card is only triggered to transmit information when in close proximity (a few centimetres) to a contactless reader.

The wireless transmission of financial data has raised concerns about digital pick-pocketing, a decidedly 21st-century crime. In theory, a perpetrator would need a portable card reader to come within centimetres of a wallet or pocket to steal data, but researchers at the University of Surrey reported being able to eavesdrop on a transaction between a card and reader from a distance of 45 cm using an inexpensive portable device concealed in a bag. It’s also possible to download apps that allow a cell phone to act as a reader, so a potential pickpocket would simply need to graze past a card with their phone.

But before consumers start wrapping their cards in aluminium foil, rest assured that EMV cards are designed to keep financial data safe in other ways: 1) the encrypted code is specific to a given transaction, and can’t be used to make new purchases; 2) information such as the cardholder’s name or three-digit security codeare not transmitted; 3) most providers have put an upper limit on wireless purchases, requiring the PIN to be entered for more expensive transactions, and; 4) if fraud occurs, zero liability is usually part of the cardholder agreement.

NFC is also central to mobile payment applications, also referred to as mobile or digital wallets, such as AndroidPay and ApplePay. A transaction can be initiated by tapping the device (i.e. a smartphone, tablet, or smartwatch)against the payment terminal, followed by a prompt to enter a passcode (or finger scan in some instances). Mobile wallets protect transactions by using tokens, randomly generated numbers that mask the primary account number to process the payment. While Apple Pay creates tokens in a chip within the phone called a secure element (SE), Android Pay uses host card emulation (HCE), which relies on the cloud, but still permits transactions without the internet by maintaining a limited number of preloaded tokens. Samsung Pay goes one step further than its competitors and uses both NFC and magnetic secure transmission (MST), which imitates the magnetic field produced by swiping and makes it compatible with both traditional and contactless card readers. The technology of digital wallets isn’t limited to physical payment terminals and can also be used to purchase things online or within participating apps.

(Left; photo from Wikimedia Commons, possibly Limulus) Microchip from an EMV Mastercard; (Right; CC0) Sketch of a card and cell phone wireless transmitting data to a card reader

The number of people using Android, Apple, and Samsung Pay has taken off over the past few year – from roughly 20 million global users in 2014 to almost 150 million by the end of this year. As impressive as this growth has been, it pales in comparison to the over 11 billion credit, debit, and prepaid cards in circulation worldwide in 2016. In Canada, mobile payments accounted for a mere three per cent of all payment transactions in 2015. Although research shows that younger Canadians are more comfortable with mobile payments than older adults, all potential users cite uncertainty about the safety of the technology as the main reason they remain reluctant to embrace mobile options. Other issues include not enough merchants accepting mobile payments and a lack of compatibility between mobile wallets and different types of financial cards and cell phones.

For now, EMV chip technology appears to offer a happy medium of increased security in the familiar shape of a credit card. But regardless of whether you swipe, insert, or tap while snagging holiday deals in stores, low-tech manoeuvres such as keeping your wallet and phone close at hand, covering the keypad while you enter your PIN, and always verifying your monthly statements remain tried-and-true ways to keep your data safe.

–30–

Featured image: Cards being swiped (left; by Ahmad Ardity CC0) and inserted (right; by Flyerwerk CC0) in a card reader

Hello, an explanation about the meaning of the function rfid

What is RFID?

Radio frequency identification, or RFID, is the general term for technologies that use radio waves to automatically identify individuals or objects.

There are several methods to identify, but the most common and simple way is to store a serial number or other information on a microchip attached to an antenna (chip and antenna with each other RFID sender or RFID tag). called).

The antenna enables this chip to transmit identification information to a reader. The reader converts the radio waves from the tagged RFID tag to digital information that can be transmitted to the computer that can be used.