Thoughts About the Closing Public Outreach Engagement Lecture of the 100th Canadian Chemistry Conference and Exhibition

Connie Tang, Chemistry co-editor

Each year, the Canadian Society of Chemistry holds the Canadian Chemistry Conference and Exhibition, better known as the CSC conference. This year’s edition, which ran from May 28 to June 1 in Toronto, marked the event’s centennial and proved to be the biggest one yet, breaking records in attendance, delegates, sponsorship, and foreign participation. As a first-year graduate student in inorganic chemistry, this was my first time attending the CSC, and it certainly did not disappoint! I left inspired, with a re-invigorated love for chemistry. I met some of my chemistry heroes, befriended chemists and industrial scientists from across Canada and the world, and reunited with old research collaborators. After an exciting, busy week, the highlight of the conference was the closing public plenary session on Thursday evening. I walked away with a stomach sore from laughter, and was moved to action after a welcome reminder of the importance and impact of chemistry research.

[I] was moved to action after a welcome reminder of the importance and impact of chemistry research.

The topic of the public lecture was “This Molecular World: From Fake News to Infectious Disease”. Not only were the five speakers engaging and hilarious, but I was very moved by their presentations. Hosted by Canadian comedian and Second City alumnus Lee Smart, the evening started with an impassioned talk from Joe Schwarcz, the director for Science and Society at McGill University. Dr. Schwarcz quickly charmed the audience with rope magic tricks and puns about ‘unravelling’ the truth about chemistry and chemicals (puns are the fastest way to win over a group of scientists). But he had a serious point: “Chemistry can look magical if you don’t know the science. But there’s also a growing paranoia of chemicals.” As a member of the chemistry community, I can attest that chemophobia tends to be fodder for eye rolling on Twitter. However, if the public is ignorant of chemistry, then, as scientists, we shouldn’t dismiss these as irrational concerns. Following this talk, I felt empowered to engage and educate the public, and then trust them to make their own sensible decisions. This talk cemented my passion for science communication, and it reminded me that I have a responsibility to demystify the science, and communicate it accurately and accessibly to the public.

I have a responsibility to demystify the science, and communicate it accurately and accessibly to the public.

If Dr. Schwarcz’s presentation was a call to action, then the following talks reinforced the amazing impact of chemistry research on society. The next three speakers, all from the University of Toronto, described the impact of their chemistry research on personalized medicine, eco-friendly fishing, and disease diagnostics.

Left: Molly Shoichet presenting on retina degradation. Right: Gilbert Walker presenting ineffective current lice control methods.

Molly Shoichet described how hydrogels (think chemical Jell-O) can facilitate the study of breast cancer cells, promote vision repair in retina degradation, and increase cell integration with the nervous system. It was incredible to see how these hydrogels helped to restore some vision in blind mice during clinical trials! Gilbert Walker talked about his research creating biodegradable materials to replace the copper coatings on nets in fish farms. His lab is also developing a multi-faceted approach to controlling sea lice, a common affliction of salmon, for which there are few available solutions. This new technology is being used in fish farms off the coast of Nova Scotia, and already shows improvements for the fish and the surrounding oceanic environment.

“How will you use your talents to fix a problem you see in the world?”– Aaron Wheeler

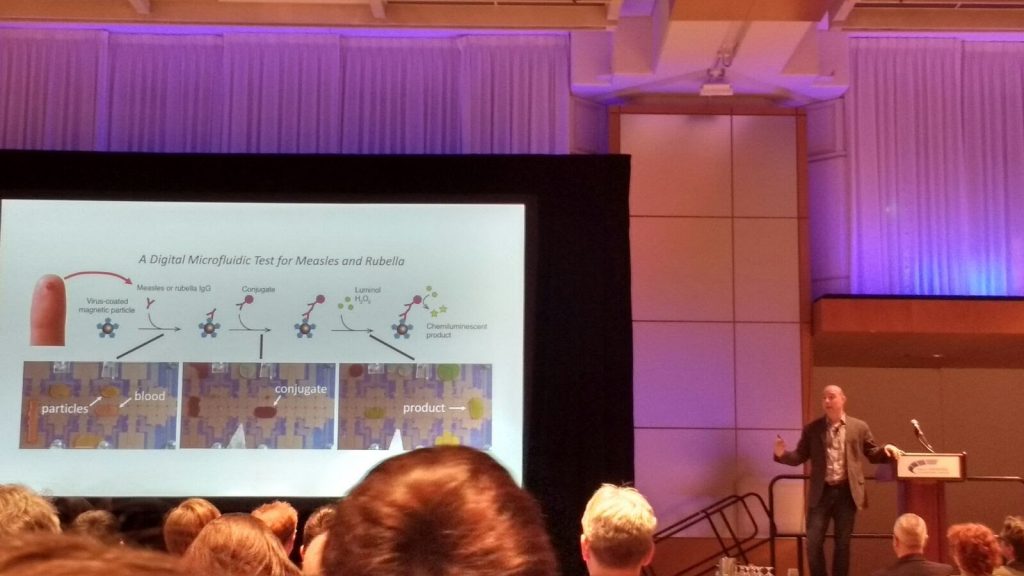

Aaron Wheeler described his research interest in digital microfluidics, systems on a chip the size of a credit card that can move, combine, and analyze tiny droplets of liquid using electrostatic forces and high-tech sensors. His lab developed $1 microfluidic chips to diagnose measles or rubella in minutes, using only a pinprick of blood! This replaces time-consuming, month-long laboratory tests. He had recently returned from the Kakuma Refugee Camp in Kenya, where these ‘labs-on-a-chip’ tested people for infections as part of a vaccination campaign. Diagnosis happened onsite, instead of sending test tubes of blood to a centralized lab. He ended his talk with an inspiring question: “How will you use your talents to fix a problem you see in the world?”

Aaron Wheeler presenting how digital microfluidics tests for measles and rubella.

These three researchers demonstrated the creative thinking essential in connecting in-lab fundamental research to real-world applications. After all, the leaps from chemical Jell-O to personalized cancer treatments, from biodegradable materials to eco-friendly fishing, or from electrostatic reactions to portable, disease diagnostics are not immediately obvious. It inspired me to think about how I could use my talents and research interests to better people’s lives.

It inspired me to think about how I could use my talents and research interests to better people’s lives.

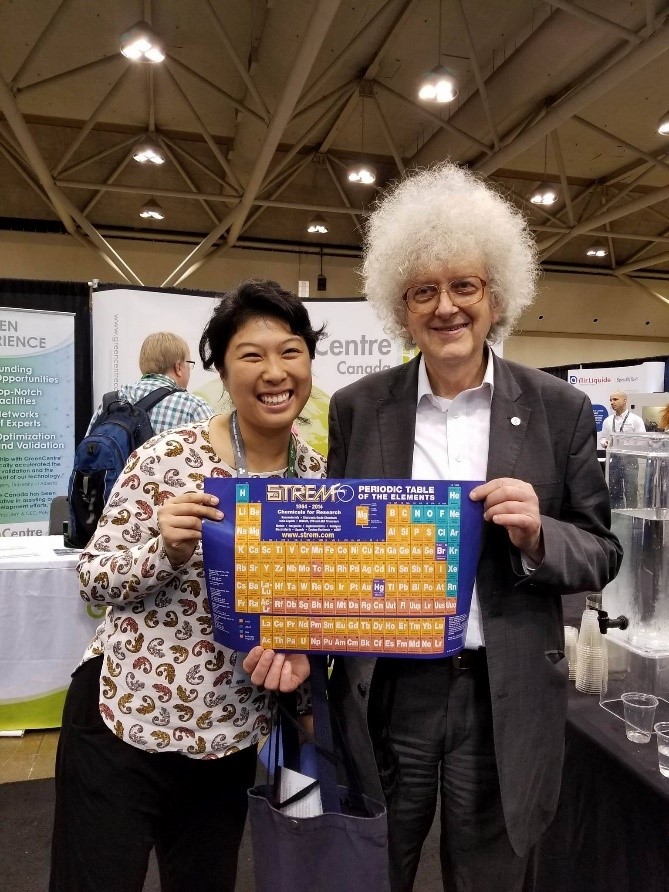

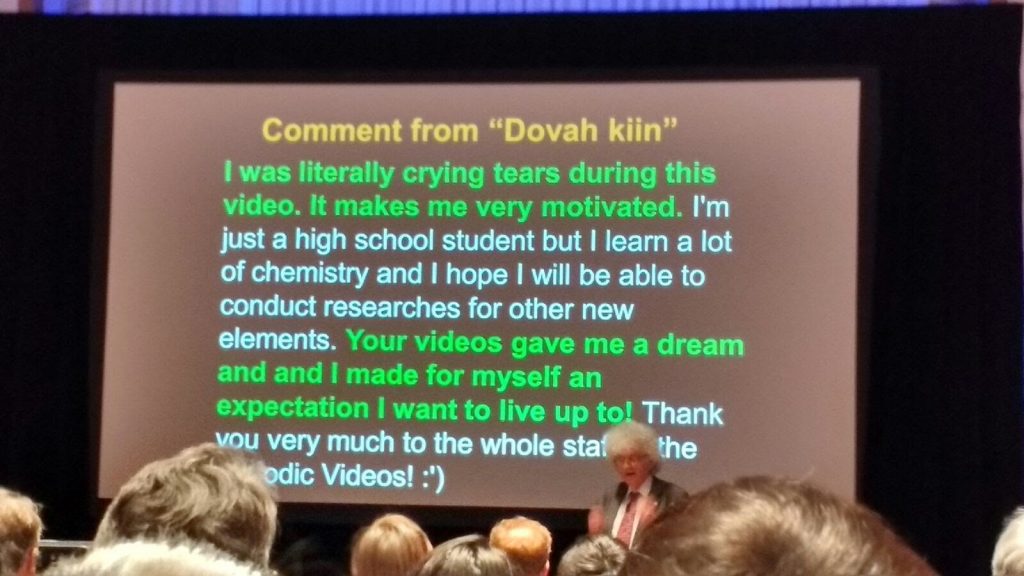

The last speaker was Sir Martyn Poliakoff from the University of Nottingham. Well known as ‘The Professor’ from the Periodic Videos on YouTube, it was quite amusing to see the huge crowds Sir Martyn attracted as he walked around the convention centre. The Periodic Videos began as a collection of 118 videos, one for each of the elements in the periodic table, and have become a forum for popular chemistry news and questions. They have gained tremendous momentum in the form of broad media attention, 938k subscribers, and over 152 million views from over 200 countries. Chemists at the CSC were certainly fans, as both students and faculty eagerly posted their selfies with him on social media (I was no exception!).

Above: Sir Martyn Poliakoff and me. Photo credit: Brian Tsui. Below: Presentation Slide from Sir Poliakoff’s Talk.

Sir Martyn graciously agreed to sit down with me and chat about his two great passions: sustainable science and science communication. As a long-time fan of the Periodic Table videos, it was thrilling to speak with him, and he was approachable, kind, and charmingly funny. Recalling his last visit to the CSC conference in 1999, he said “Chemistry has moved on since then. It has expanded, but people’s enthusiasm hasn’t wavered. I’m pleased to meet so many fans and also to meet some very enthusiastic chemists. I think with my hair I’m easily recognizable. It’s very nice meeting new people. I’m looking forward to meeting some more.” Part of being a good science communicator is that approachability and engagement with others.

Personally, the biggest lesson for me was that research and outreach are not mutually exclusive.

His talk, titled ‘From Test-tube to YouTube’, detailed the origins of The Periodic Table video series, and he described the periodic table as “a kind of family photograph”. While he joked about his hair, highlighted his visits to gold vaults and sunny beaches, and passed around a dog toy that mimicked the structure of methane, Sir Martyn demonstrated that people are curious about chemistry and eager to learn more. Personally, the biggest lesson for me was that research and outreach are not mutually exclusive. I can continue to pursue my passion in science communication while pursuing my career in research.

As a chemist conducting research in a lab every day, it can be easy to get bogged down in experimental details and lose sight of the incredible impact research has. I was humbled by this plenary session. I walked away with tears in my eyes. It placed chemistry in the context of everything that I do in my academic life. It reinforced the idea that we have responsibilities as scientists. Research we do in the seemingly isolated confines of a lab can provide tangible improvements to people’s well-being.

Chemistry can change the world.

* Header Photo: The conference banner at the industrial exhibition. Credit: Chemical Institute of Canada