Katrina Vera Wong and Raymond Nakamura, Multimedia co-editors

What if Swan Lake were a thesis on avian reproductive strategies? Or The Nutcracker were a paper on the psychoactive effects of glucose on juvenile neural pathways? The cerebral rationality of science and the physical emotionality of dance might seem like awkward partners, but such collaborations can produce delightful results.

Dance can be the subject of scientific study, as in this TED-Ed animation in which physics laws were applied to a notoriously difficult ballet move – the fouetté – in Swan Lake, enabling us to appreciate the move and understand how it’s possible.

Scientific studies can also be applied to dance itself, similar to how sports incorporate scientific coaching methods to improve performance. For example, Jeff Russell, an assistant professor of dance science, studies the feet of tap dancers to analyze the forces involved in subtle movement. Dance, especially professional dance, can have an intense effect on the dancer’s body, and science can help us understand what happens when the body is subjected to that level of exertion. It can also be used to improve a dancer’s performance on stage or on the dance floor.

Conversely, science can be the subject of dance. Vancouver-based Curiosity Collider, co-founded by Science Borealis outreach maven Theresa Liao, is dedicated to promoting collaborations between scientists and artists including dancers. In the Neural Constellations project, a study about the benefits of dance for Alzheimer’s patients grew into a dance performance about how memory degenerates. One of the participants, Cheryl Wellington, who studies genetic and environmental risk factors for dementia, talked about the value of dance for its physical and cognitive stimulation. Dance can have positive effects on thinking in general.

At another Curiosity Collider event on the theme of quantum mechanics, Lesley Telford, of Inverso Productions, choreographed a performance inspired by quantum entanglement. Named after Einstein’s phrase for the phenomenon, Spooky Action was produced in collaboration with interdisciplinary artist Barbara Adler to put a poetic spin onthe concept of particle connectivity. Spooky Action helped one of us (Kat) visualize what happens in quantum entanglement – so, even if not explicitly intended, it really was a form of science communication.

Gonzo scientist and Dance Your Ph.D. founder John Bohannon, who has a doctorate in molecular biology, is a keen advocate of the use of dance as science communication and even presented a TED Talk choreographically arguing for the use of dance instead of Powerpoint. Dance Your Ph.D. is a contest sponsored by the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) that invites science-related Ph.D.s to interpret their work as a dance. Tips include “Start with a clever idea”, “Become the dance,” and “Have fun.”

We asked Stephanie Prezioso about her experience participating in this contest. She choreographed and performed in Listeria Hysteria while completing her Ph.D. in cells and systems biology at the University of Toronto. Rather than summarizing an entire thesis, the dance focused on particular ideas within the work. Making specialized technicalities comprehensible to an educated adult can be a challenge, and dance is often combined with narration or post-production labeling to clarify the concepts being illustrated.

“The concepts [my] dance explains are complex and would have been difficult to interpret without additional explanation,” Prezioso says. “This is common for Dance Your PhD entries, which often either have text or verbal explanations to accompany the dance.”

As for the content itself, Prezioso notes, “When explaining specialized complex concepts to a general audience there is always a tradeoff between keeping the details and making it accessible, and achieving a balance for your target audience is key.”

This is true of science communication in general. But what makes this approach unique is the transformation of scientific concepts into form and movement, as Prezioso shows in describing one scene: “To show how four molecules come together and bind to the DNA, I had a partner-balancing scene planned. The goals the scene had to meet to be scientifically accurate were that the four people had to first join as pairs, and then the pairs would join as a quad and bind to the DNA, but the specific choreography was written in collaboration with the dancers in the scene.”

The dance-science method “could be a powerful tool for science communication,” says Prezioso. “It is important to supplement dry data-driven writing with an accessible and more entertaining form, such as dance.”

Learning to share one’s scientific ideas through dance can be a valuable experience for a scientist and can have positive impacts on the audience and even on the environment. This can be further enhanced when the audience is not simply watching but participating and learning the dance and, through it, the scientific concepts.

If you’re looking for a way to share your scientific idea, why not try dance? As a Japanese proverb says, “The dancers are fools. The watchers are also fools. So you might as well dance.”

What are your favourite examples of science partnering with dance?

~30~

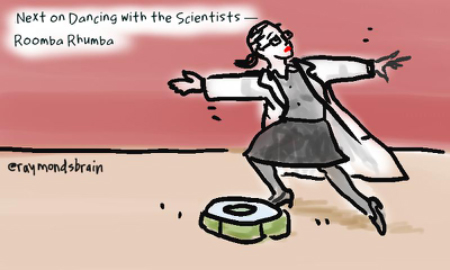

Banner image by Raymond Nakamura, Raymond’s Brain.

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/edmonton/dance-your-phd-pramodh-senarath-yapa-physics-university-of-alberta-1.5022123

2018 Dance Your PhD winner from the University of Alberta