Nahomi Amberber, Policy & Politics co-editor

Do you remember how many times you’ve been prescribed an antibiotic or used an antifungal cream for an unexplained rash? Most people don’t either, which speaks volumes about the role antimicrobials play in modern healthcare. It also highlights the threat of antimicrobial resistance to global health.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR), which includes antibiotic resistance, is the term used when microbes (bacteria, parasites, fungi, etc.) are no longer susceptible to the drugs we’ve developed to fight them. From artemisinin-resistant malaria to the 11-day evolution of a resistant strain of E. coli in this popular YouTube video, the fact that AMR takes many forms and pays no attention to state borders makes it a global problem. That’s why in September 2016, the United Nations General Assembly dedicated a meeting to the issue. Improving public knowledge and promoting professional best practices were the main goals. And countries have a vested interest in supporting them: it is projected that in 2050 there will be 10 million AMR-related deaths worldwide.

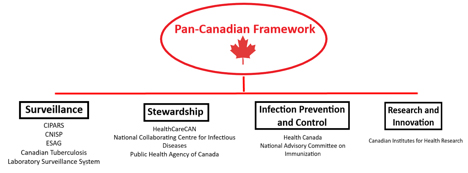

In Canada, the urgency of this issue has resulted in several government agency initiatives, including the 2014 Federal Framework for Action, the Federal Action Plan in 2015, and the Pan-Canadian Framework for Action in 2017. The 2017 framework lists surveillance; infection prevention and control; stewardship; and research and innovation as its main components. It also highlights some of the challenges: surveillance gaps in certain settings, inconsistent stewardship efforts, and a lack of antimicrobials, among others.

Major government agencies, systems and stakeholders supporting the framework. Diagram: Nahomi Amberber

Major government agencies, systems and stakeholders supporting the framework. Diagram: Nahomi Amberber.

But what’s most important is how the government is actually following through on these fronts.

For surveillance, the Canadian Integrated Program for AMR Surveillance (CIPARS) brings together a range of systems that watch out for infections acquired in hospitals, specific microbes of interest, and laboratory references. The data from these systems are the basis for the Canadian Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (CARSS) Report, published annually since 2015. It focuses on resistant microbes specific to Canada and where we find them.

Stewardship, the component that focuses on knowledge translation for professionals and the public, is supported by the federal government. Stakeholders such as the National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Diseases and HealthCareCAN teamed up to publish a national plan on the matter in 2016.

Infection prevention and control have mainly been targeted through public health initiatives such as vaccination projects and educating healthcare professionals.

Finally, efforts to develop new antibiotics are funded primarily through agencies such as the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, which awarded $96 million to AMR research between 2010 and 2015. This is important because there has been a dearth of new antimicrobials developed in recent years. According to a new World Health Organization report, the number of drugs in the clinical pipeline is dangerously low.

And while these initiatives are heavily geared towards research, they have resulted in policies that affect all Canadians. In November 2015, Health Canada made new precautionary statements mandatory for antibiotics. The statements make it clear that antibiotics taken in the absence of susceptible bacteria are “unlikely to provide benefit to the patient and [risk] the development of drug-resistant bacteria.”

The application of rules is also changing. For example, farmers will soon have to deal with new regulations regarding the use of antibiotics in livestock. Last month, importing antimicrobial drugs used to treat human infections with the intention of using them in livestock was banned. A new program favors the use of veterinary health products, with antimicrobials requiring a prescription from a veterinarian as of December 2018. Since resistant microbes can transfer from livestock to humans, this is an important step in stopping the development of AMR by decreasing the preventative use of antimicrobials in animals.

But the fight against AMR doesn’t stop at the federal level – everyone can participate in anti-AMR practices. Start by taking this handy World Health Organization quiz to challenge your knowledge of AMR and what contributes to it. Spread this information to others. It will strengthen public knowledge and preventative measures – something we’re going to need if we don’t want our kids to live in a post-antimicrobial world.

–30–

Feature photo: qimono, CC0, via pixabay.com