Hayley Rose Reekie, New Science Communicator

In a world of ever-evolving technology, scientific equipment constantly becomes outdated. Universities regularly exile old research equipment to storage rooms and then forgot about it.

I recently set out on a mission to find some of these relics and to discover their stories. Here are the stories of seven forgotten laboratory treasures hidden away in Simon Fraser University’s (SFU’s) storage rooms.

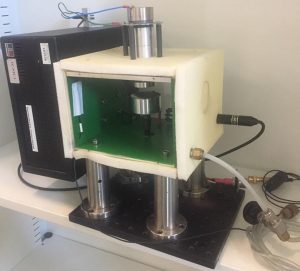

Sonic Levitator

In the Chemistry department’s storage room, a sonic levitator caught my eye. It uses sound waves to levitate particles that would otherwise fall under the force of gravity.

This machine was used by Neil Draper when he was a graduate student in George Agnes’s lab. Unlike chemical reactions done in containers, levitated particles have no surfaces to interact with, and can crystallize into different structures. This is just like how the graphite in your pencil and the diamond on your ring are made of the same material, the only difference is that they formed under different conditions.

Less research is being done in this area these days, thus this tiny piece of machinery has been relegated to the basement.

French Press

This process is required for internal cell studies like genetics and immunology. The French press has been replaced by new cell-breaking techniques, such as sound waves, homogenizers (a fancy blender), or various chemicals and enzymes. The last time the Press was used was over a decade ago in Mark Paetzel‘s lab, where researchers were trying to extract proteases that were too sensitive for any of the new methods. It now sits dormant, with its log book empty.

Little Portable Light Meter

Tucked away in Biology storage is a small, worn wooden case that holds a Photovolt light meter, circa 1948. It uses a selenium cell to measure brightness in footcandles. Yes. Footcandles. That used to be the standard measurement for light intensity (we now use units of lux). These light meters ensured consistent exposure for photographs, which were and continue to be a vital tool in biology, providing a physical representation of experimental results.

Today, researchers use digital, electric meters, as they’re much more portable, resilient to damage, and precise. With all that against it, it seems that the Photovolt will never see the light of day again.

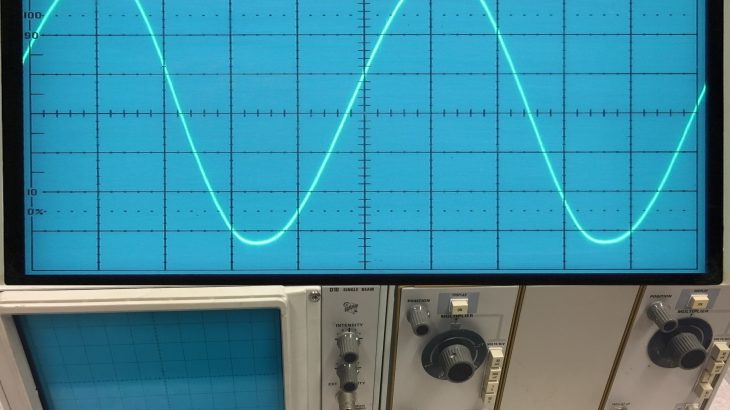

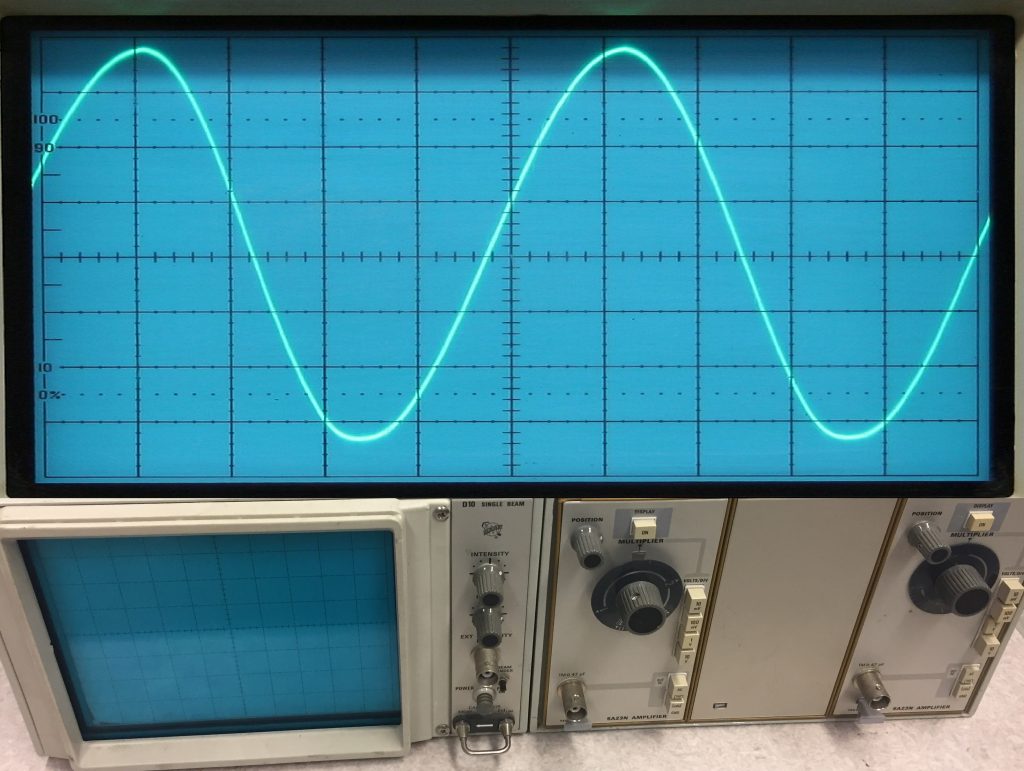

Analogue Oscilloscope

This analogue oscilloscope was on top of the Physics Student Association fridge, after being rescued from a garbage pile in the dungeons of the Physics department. Oscilloscopes detect changes in voltage over time, and are not only a learning tool in electronics, but a troubleshooting tool for any circuit. Although they’re still a staple in today’s physics labs, they’ve been replaced by new, electronic versions. This model is from 1971, and hasn’t been used in a long while. That being said, this little machine helped educate a generation of SFU physics students.

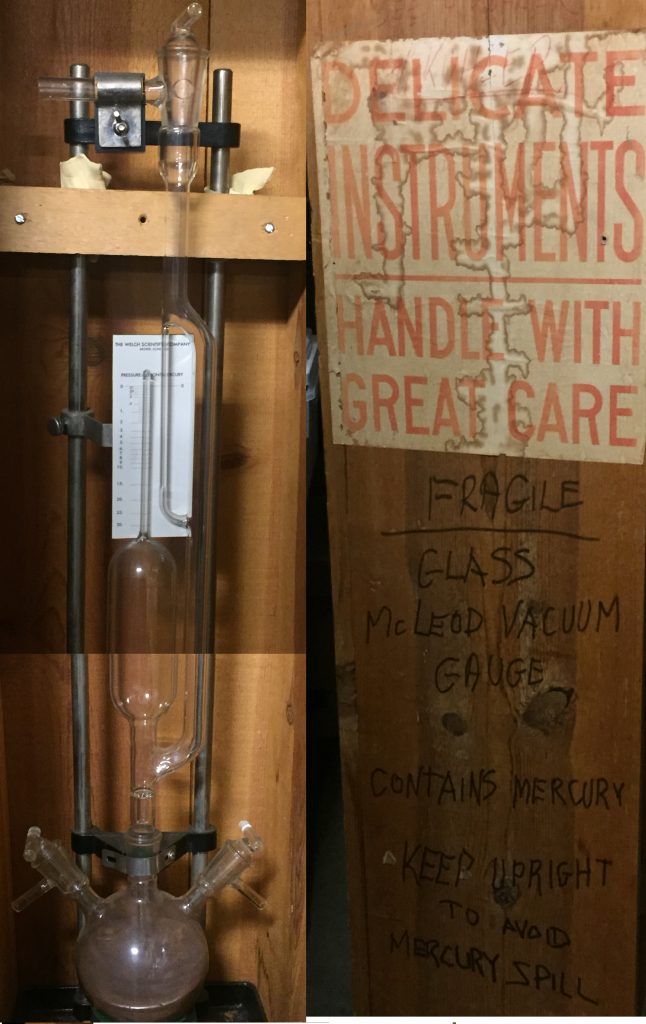

McLeod Vacuum Gauge

This piece of equipment required the most caution of all of those that I found. Once you get over your fear of the half a litre of mercury sitting in the bottom of the instrument, the McLeod vacuum gauge is quite interesting. It was used to measure systems that were under high levels of vacuum. As the pressure decreased, the mercury was drawn up into the tubes, allowing researchers to measure the vacuum pressure. Electronic vacuum gauges have replaced them. Besides being much safer, they are also more accurate.

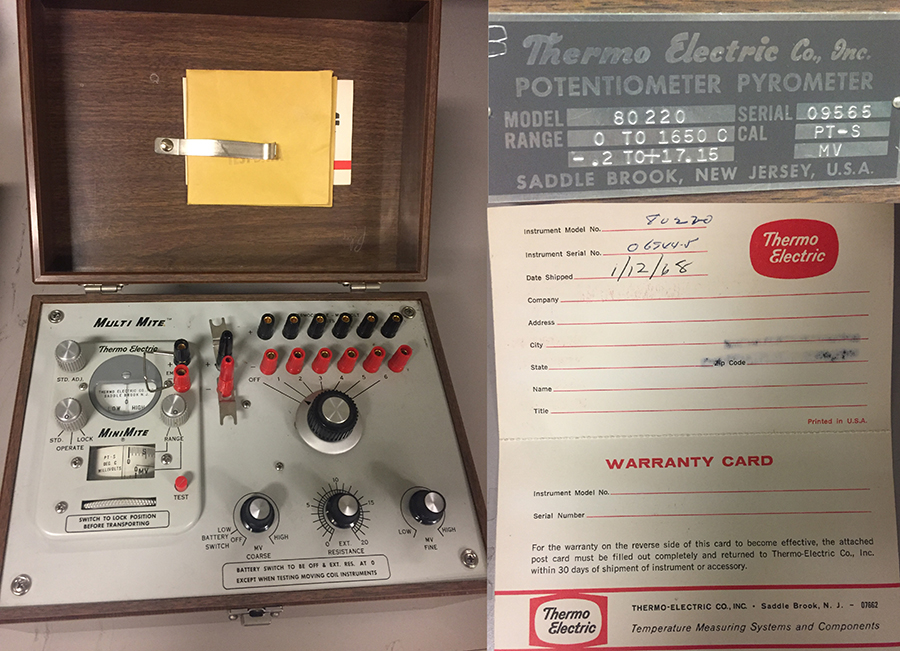

Potentiometer Pyrometer

This little wooden box’s name is quite the tongue twister. The potentiometer part of the instrument is a set of resistors that can change the voltage of a circuit, which is what you find in light dimmers and volume level controls. The pyrometer is able to measure the temperature of circuits by converting the heat energy to voltage. The warranty card is from 1968, making this instrument 50 years old this year. Although the warranty lasted only one year, the machine is in surprisingly good condition. It’s been replaced by smaller and more compact devices.

Gamma-ray Spectrometer

This spectrometric gem was donated to the Earth Science department by a mining company, holster included. It detects Gamma rays given off by radioactive elements such as uranium, plutonium, and thorium. These hand-held meters were taken out in the field on exploration trips. Not only can these be used to scope out potential ores for commercial use, they can be used to detect if rocks are from the same – or separate – rock formations. These days, spectrometers are portable and easily thrown into a backpack. Unlike this one, which lives in a briefcase.

~

What is the fate of these instruments that have served us well in their time? Although they may have reached the limits of their use, they are a part of scientific history. They deserve a shelf in a museum, but no one has room to take them. So they sit in storage rooms until someone decides they are taking up too much space. Then they are sent to surplus and disposal or to an electronics recycling plant.

~30~