Katrina Vera Wong, Multimedia co-editor

If you’ve heard of the terms “science art” or “sciart,” you’re probably familiar with the idea of using visual art to represent, explain, or bring attention to some aspect of science. The wonderful realm of art and science is capable of teaching science in creative ways and is a potent tool for science education.

While you can learn a lot from looking at sciart, you can learn even more by creating it. “Spectacle has a role to play in science centres and science learning – but … it plays less of a role than most people realize,” Devon Hamilton of Playful Content says. “It is an attractor and attention getter, but the deeper learning – the more memorable learning, the learning that is about skills – is often built by those quieter, longer, more involved moments.”

Naturalists and taxonomists have been collecting plant specimens for centuries. It’s an activity thatall agescan enjoy. At 14 years old, Emily Dickinson laid out a collection of pressed flowers from Amherst, Massachusetts in a green leather-bound album. This herbarium has become a treasure of Harvard’s Houghton Rare Book Library.

Last year, I had a serendipitous encounter with the Vancouver-based Herbarium Project. It skilfully brought together the act of doing science (collecting and identifying plants) and doing art (creating a scrapbook of beautiful and engaging material). Ethnobotanist and media artist T’uy’tanat-Cease Wyss led a grade-6/7 class from Lord Strathcona Elementary School through this project, which was part of an off-site exhibition by the Contemporary Art Gallery. Wyss took the students to Trillium Park, Harmony Garden and other natural spaces to gather and learn about plants.

“It teaches them how to be mindful and teaches them a meditative way to be in nature by touching things and feeling it and understanding that it’s alive, like they are,” Wyss says with patent sincerity. “That was kind of an epiphany moment for them: they had to realize that there are some plants that grow in abundance and there are others that grow very slowly and have a specific purpose. And that not all plants are there to pick.”

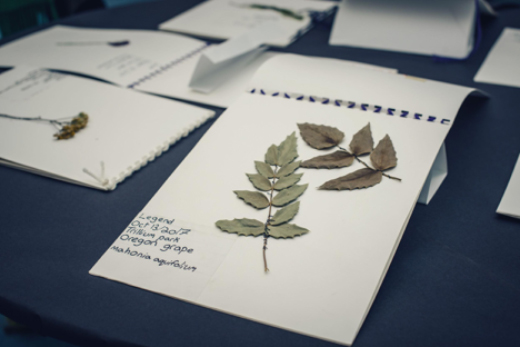

The plants that were picked were taken back to the classroom for identification and mounting. Using a unique method adopted from Wyss’ daughter, specimens were positioned and hand-sewn onto sheets of paper, where students also handwrote information about their specimens. Then the sheets were assembled into individual booklets, from which a selection was compiled to form The Herbarium Project.

The Herbarium Project, 2017, Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver. Photography by Four Eyes Portraits.

In science-speak, a herbarium is mostly known as a large archive of regional flora – I’m talking tall metal cabinets stacked with sheets and sheets of organized plant specimens, all labelled with information like who collected the plant and where it came from. But what makes The Herbarium Project remarkable is that it recalls an old Victorian practice of collecting flowers in what the Smithsonian Gardens calls botanical scrapbooks.

This project combined art, science, outdoor settings and an indoor craft, and even students who had trouble focusing before did everything necessary for this project. Wyss, markedly impressed, says, “They learned a lot but I could really see that they were teaching.” A student even schooled his mother on the importance of scientific accuracy as he diligently searched for the names of his specimens.

The Herbarium Project, 2017, Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver. Photography by Four Eyes Portraits.

Plant information was mostly found in books or taught by Wyss. The only time students used an electronic device was to retrieve the latitude and longitude of the location of their plants. “I think no matter how pretty modern technology is, we have to encourage kids to touch and feel nature and to understand it’s the first technology,” Wyss maintains. By sharing and highlighting indigenous knowledge of the plants, Wyss hopes to “create more stewards of these [natural] spaces” – a teaching philosophy that propels a new vision of Canadian science education. Unfortunately, without a teacher like Wyss, this kind of art-science project might be hard to do.

For learning at home, the best way to teach science is to merge it with a story, suggests Derek Wulff, designer of Pathfinders. “I mean, everything that’s interesting is a story,” he says. One of his kits, called Youtopia, is a moving diorama that you design and build. Its movements are a little limited but unlike other DIY projects that involve, for example, painting an assembled robot, Youtopia is open-ended. Having “no predetermined outcome,” it calls for imagination and artistic flair. You could use it to tell a story, demonstrate a predator-prey relationship, design a rockin’ birthday card or make the cow jump over the moon.

And because it can be anything, Youtopia strikes me as the sort of kit that is not only open to art, but also open to failure. Sara Whitlock, in STAT, makes an interesting point: “We need to keep talking to younger science students, when appropriate, about our failures so that they’ll know their own similar failures aren’t career-crushers.” (Check out #ScienceFails for some real world examples.) The search for truth and solutions isn’t easy but it’s important to persevere. If art teaches us to be open-minded, bringing it into a science lesson could open a dialogue with students on how mistakes and setbacks are intrinsic to the process.

In a broad sense, these projects fall into the realm of sciart and present an interesting opportunity for science education. Deviating from the tired facts-and-figures method of teaching, they introduce an artistic aspect to learning and a level of involvement that might better capture students’ interest.

~30~

Banner image: The Herbarium Project, 2017, the Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver. Photography by Four Eyes Portraits.