Sarah Boon and Sri Ray-Chauduri, Environment and Earth Science co-editors

Earth Day falls on April 22 this year, and in celebration many organizations are dedicating this entire week to Earth Week, running from 20-24 April. Events are being held around the country for everyone from kids to university students to adults, hosted by institutions like the University of Waterloo, science centres like Vancouver’s Science World, and community groups like the Summerland Arts Council.

Here at Science Borealis we’re celebrating Earth Week by taking a closer look at some new science that’s come out in the past few weeks relating to the global ocean.

Usually when we think of climate change we focus on land-based impacts – things that we’re familiar with and that impact us directly. For example, increased frequency and intensity of wildfires, more intense heat waves, coastline erosion, glacier retreat, later river and lake ice formation in fall and earlier spring breakup, and more.

As Chris Hadfield’s outreach from the International Space Station last year reminds us, however, 71% of globe is covered in ocean. Thus changes in our oceans have a big impact on climate, with ocean-atmosphere connections subsequently driving many of the changes we observe on land.

Recent research on both the Pacific and the Atlantic Oceans has revealed new facets of these connections, which may have broad-reaching consequences for our climate future.

- Warming in the Pacific Ocean

In 2013, researchers observed a large mass of warmer-than-average water in the Gulf of Alaska that they (very technically) named the ‘blob’. By summer 2014 it had expanded to the California coast, and by late 2014 filled the entire northeast Pacific Ocean. The blob ranges from 2-7°C warmer than normal, and has developed into a long, skinny feature that stretches from Mexico to Alaska.

A recent study linked the blob to changes in West coast marine ecosystems, including the loss of copepods, an important food source for salmon, and to starving sea lion pups and Cassin’s auklets sea birds. Additionally, air moving inland over this warmer water transports more heat and less precipitation, possibly contributing to the Pacific Northwest’s warm summer of 2014, the as well as to the ongoing California drought. Here on southern Vancouver Island we saw very little rain and high temperatures for weeks on end last summer, with some serious ramifications for our well water supply.

Zooming out from the west coast in particular and into the Pacific Ocean basin overall, a second study found that this 2013-2014 ocean warming is linked to above-average sea surface temperature in the tropical Pacific Ocean. This bigger pattern may have contributed to weather ‘weirding’ by creating an atmospheric wave that led to high pressure over western North America – which has seen record low snow packs and warm temperatures, and low pressure over the East – which has seen the opposite with record breaking snow falls and cold temperatures.

With only a few years of data, these patterns can only be attributed to natural climate variability, but they may foreshadow what could happen under predicted future climate conditions.

To read more about these phenomena, see Sarah Kaplan’s article for the Washington Post and this great image comparison from NASA’s Earth Observatory.

- Cooling in the North Atlantic Ocean

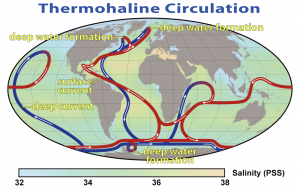

If you’ve ever watched the movie The Day After Tomorrow, then you’re likely familiar with the concept of the thermohaline circulation (THC). It’s a global ocean current that acts as a conveyor belt, moving warm water from the Gulf Stream up to the North Atlantic, where it cools and sinks, then flows down to Antarctica, where it upwells and flows back up to the North Atlantic via the Gulf Stream again. This process also happens in the Pacific and Indian Ocean basins, transporting water and heat between equatorial and northern parts of the oceans.

Graphic of the thermohaline circulation from NOAA (public domain).

While the movie stretched the whole THC concept well beyond the limits of scientific credibility, a recent study in Nature (open access) shows that the THC is actually slowing down in the North Atlantic.

What’s causing this slowdown? Researchers suggest that it was initially caused by increased melting of sea ice, which led to more freshwater in the North Atlantic. Since freshwater is less dense than salt water, the current can’t sink as effectively, thus the conveyor belt can’t ‘pull’ as much warm water up from the south. Since the 1990s, however, it seems that increased glacier melt from the Greenland Ice Sheet is contributing to freshening of the North Atlantic, with the same impact. Measurements from the North Atlantic show that the water is getting colder, another indication that warm water from the Gulf Stream isn’t making its way north.

The study estimates the circulation has weakened by about 15-20%, and while it’s not the end of the world (as we know it), there will be impacts. These include some cooling in Europe (which may be offset by global warming), and sea level rise off the US east coast. For a more detailed explanation of how this works, see Chris Mooney’s article in the Washington Post. There will also be weather changes – although researchers are working to determine specifically what those might be.

—

Astronauts aboard the International Space station orbit the Earth every 92 minutes and are easily able to see how the oceans, atmosphere, and land connect with weather. But for those of us looking to the sky from Earth’s surface, these interconnections are far less obvious. So during this Earth Week, consider the oceans, and take a step back and appreciate how so many systems come together to make our planet home.

One thought on “It’s Earth Week! Have you thought about our oceans lately?”

Comments are closed.