Kylie Hutt, New Science Communicator

All it took was one ultrasound image to change all of our plans.

I was part of a research team from the University of Saskatchewan’s Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM) investigating how llamas ovulate. The season was just gearing up and we were doing the usual reproductive-function exams on the 25 research llamas at the college’s llama and alpaca farm near Saskatoon.

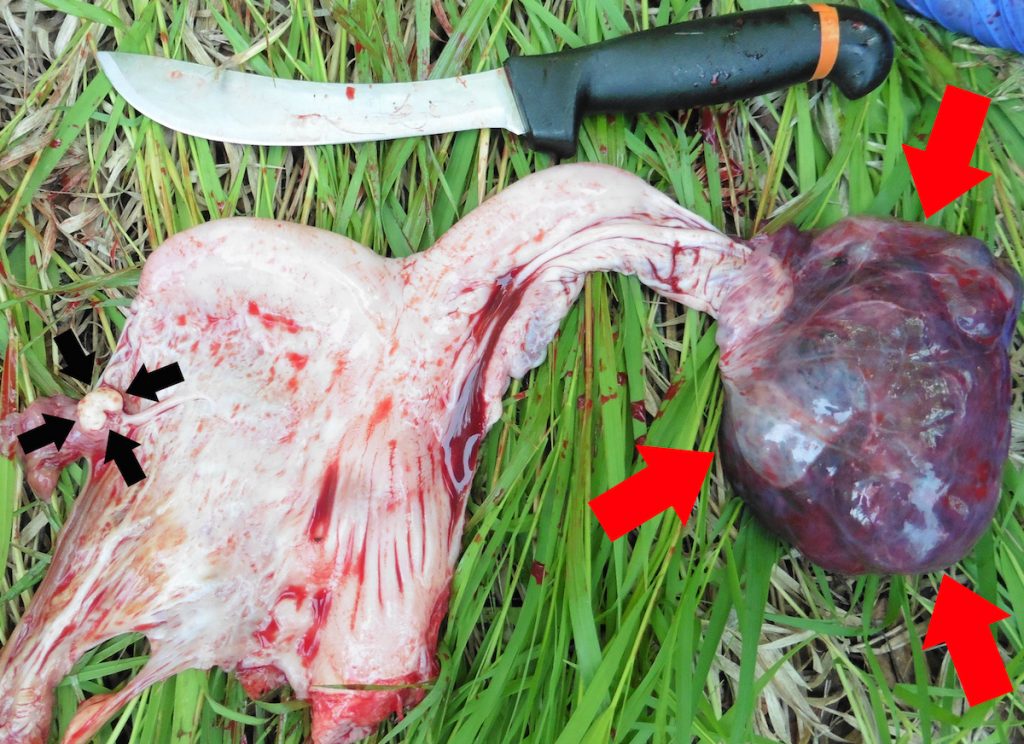

But a routine ultrasound examination on one of the llamas, named Touch of Magic, revealed an ovary that didn’t look right. On ultrasound, a normal active llama ovary should look ellipsoidal in shape and should be about 2 X 2 cm in size. Depending on the phase of follicular activity, one should see numerous small or a couple large, perfectly spherical dark fluid-filled cavities.

Touch of Magic’s ovary appeared to be enlarged, approximately 10 X 12 cm, and was full of irregularly shaped, fluid-filled cavities, resembling a honeycomb shape. Her other ovary appeared to be inactive.

She also had a history of trying to mate with other females in the herd and would even make the gurgling sound that males make while mating – unusual behaviour for a female camelid.

Our initial findings led us to speculate that we had discovered a granulosa cell tumour. But before we could confirm the diagnosis, we had a lot of work to do.

Seeking the secrets of llama reproduction

Researchers in the college’s Department of Veterinary Biomedical Sciences have been studying mammalian reproduction for decades. Their work continues to advance our understanding of reproductive function across a diverse array of livestock species such as cattle, camelids and bison, with implications for human reproduction, too – providing insights and potential solutions to the biological challenges of reproduction in all mammals.

A recent discovery by a research team associated with the laboratory of Dr. Gregg Adams, a WCVM veterinary scientist known internationally for his classic studies on ovarian function and fertility in cattle, camelids, bison and humans, deals with the mechanics of ovulation in llamas (Lama glama). Instead of ovulating cyclically in response to a repetitive sequence of changes in sex hormones like other mammals do, camelids – llamas being one of the six living camelid species – ovulate in response to a protein called ovulation-inducing factor (OIF) present in the semen of males.

Because the act of copulation in itself had long been thought to induce ovulation in llamas, the discovery of OIF’s role answered some questions, but led to many new lines of investigation. One of these involves looking at how and where OIF exerts its ovulatory effect.

“It appears to occur at the level of the hypothalamus,” says PhD candidate Rodrigo Carrasco, who is studying how OIF acts on the camelid brain. “However, we haven’t pin-pointed which neuron is triggered. We’re also interested in understanding which other molecules mediate the process.”

Llamas patiently await treats after an ultrasound exam. The llama (Lama glama) is one of six living camelid species. Photo: Kylie Hutt

I joined Adams and Carrasco to try to answer those questions. But what started out as a straightforward, planned-out field season quickly changed to answering a new, urgent question – what was going on with Touch of Magic?

Granulosa cell tumours

Granulosa cell tumours are a type of ovarian cancer that forms in the granulosa cells of an ovary’s follicles.

To our knowledge, the first documented case of this kind of a tumour in a llama occurred in 2010. Additionally, another granulosa cell tumour was reported in a dromedary camel in 2013. Although the tumours are occasionally seen in other species – and account for about two to five per cent of ovarian cancers in women – these are the only two reports of granulosa cell tumours in camelids that we know of.

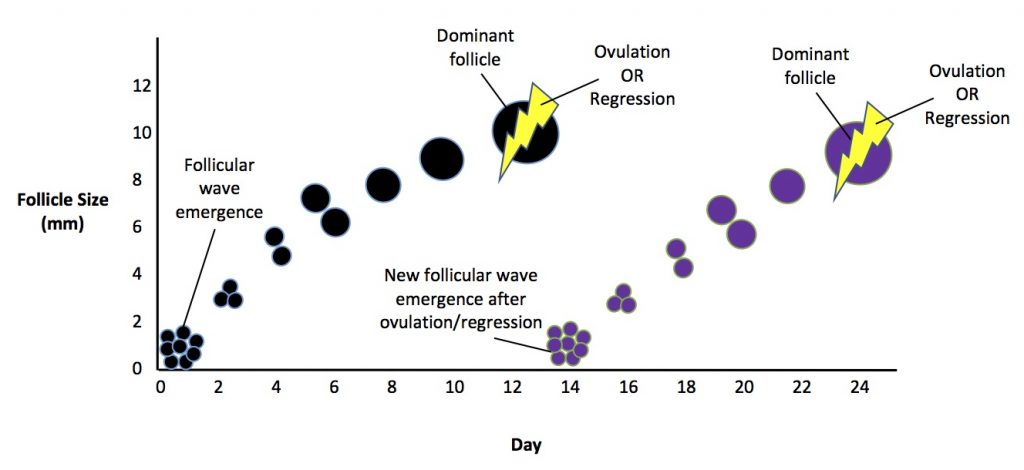

In a healthy camelid, numerous spherical growing follicles of many sizes protrude from the surface of the ovaries. These follicles house immature egg cells that are waiting to be fertilized upon ovulation.

Follicles continuously grow and shrink in waves. With each wave, only one follicle becomes the dominant ovulatory follicle, and all of the other subordinate follicles regress.

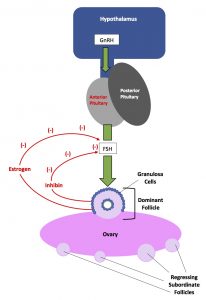

Each dominant follicle is lined by two major types of cells – theca cells and granulosa cells. Both cell types help the follicle mature and prepare it for ovulation.

Hormonal feedback resulting in growth of the dominant follicle and regression of the subordinate follicles in a llama. Image: Kylie Hutt

The process of follicular growth and selection of the dominant follicle is mediated by many hormonal changes:

- The hypothalamus, a small region of the brain, releases gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH).

- The release of GnRH triggers release of follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) from the anterior pituitary gland, a part of the brain that is nestled beneath the hypothalamus.

- FSH in turn stimulates follicles to grow, as well as multiplication of granulosa cells in the dominant follicle destined to release the egg it houses.

- The granulosa cells then release high levels of estrogen and inhibin – both hormones feed back to the pituitary to inhibit FSH release. Granulosa cells are estrogen- and inhibin-production powerhouses in the dominant follicle.

- With less FSH circulating, the non-dominant follicles regress and the dominant follicle prepares to ovulate.

In granulosa cell tumours, granulosa cells multiply out of control. This causes morphological changes in the ovary and can result in excessive production of three key reproductive hormones – estradiol, inhibin and anti-mullerian hormone.

The diagnostic process

We conducted a thorough physical examination on Touch of Magic, as well as extensive blood tests. The results of both revealed nothing unusual. Furthermore, the llama wasn’t displaying any signs of pain or depression, and she was in great body condition.

However, when we measured Touch of Magic’s hormone levels, we found her plasma estradiol concentration was 180 picograms/millilitre – well over the normal reference range of 5–30 picograms/millilitre.

“Such drastic hormonal changes are very characteristic of granulosa cell tumours,” Carrasco says.

In addition to the ultrasound image of the ovary and the abnormal sexual behaviour, the elevated plasma estradiol was the third and final clue in our diagnostic process.

Confirmation

The principal treatment for granulosa cell tumours is surgical removal of the affected ovary. Upon removal, peripheral sex hormone levels return to normal and the opposite ovary returns to normal function.

That was our treatment plan for Touch of Magic. However, she died unexpectedly just days before the scheduled surgery.

Granulosa cell tumours can be benign or malignant. If they’re malignant, the cells will often spread from the primary tumour and seed themselves into other distant organs throughout the abdomen.

When we necropsied the animal, we found the ovarian tumour and a second mass nearby in the abdomen. It appeared Touch of Magic died of acute abdominal hemorrhage, likely due to rupture of the second mass which was well supplied with blood.

Touch of Magic’s reproductive tract. The right ovary (red arrows) is enlarged and appears to be multi-lobed on the surface. The left ovary (black arrows) is small in comparison but resembles a normal inactive ovary. Photo: Kylie Hutt

Although we were unable to treat Touch of Magic in time, finding the tumour and sharing the information with a larger research audience allows us to advance medical and veterinary scientific knowledge. “Through sharing the manifestation and chosen treatment of this tumour, we can hopefully help other experts in the field understand this type of cancer to a greater extent,” says Carrasco.

And the more we learn about granulosa cell tumours, the better prepared we will be to more efficiently and effectively respond to this disease in all mammals – in camelids and even in women.

~30~

Kylie Hutt is a student at the University of Saskatchewan’s Western College of Veterinary Medicine. She wrote this post as part of Science Borealis’s Summer 2018 Pitch & Polish, a mentorship program that pairs students with one of our experienced editors to produce a polished piece of science writing.

Read more about Pitch and Polish and other New Science Communicators programs>

Join us every Monday this month to read works by our other Pitch and Polish graduates:

January 7, 2019: Veterinary researchers seek clues to more effective treatment for deadly dog disease, by Nolan Chalifoux

January 21, 2019: Small, deadly parasite emerging in Canada’s North, by Mila Bassil

January 28, 2019: Ramp walking helps diagnose lameness in dogs, by Emma Thomson

February 4, 2019: Multidisciplinary collaboration helps researchers solve complex, real-world problems, by Harrison Brook