Ainslie Butler and Lindsay Jolivet, Health, Medicine, and Veterinary Science co-editors

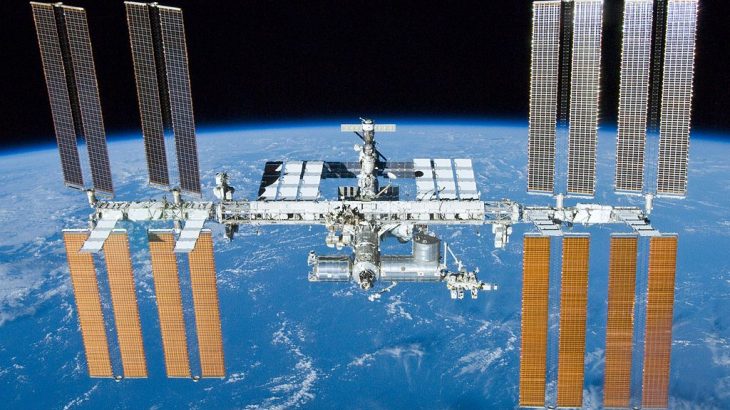

In mid-February, NASA launched a superbug into space. The idea was to study how methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, or MRSA, mutates in the microgravity environment of the International Space Station. Using space to predict the future of this deadly pathogen could give us a head start on developing vaccines and drugs to fight it.

Research has shown that bacteria can grow better in microgravity, mutating faster and potentially becoming more deadly. It’s like pressing ‘fast-forward’ on normal bacterial growth. The hope is that by observing this accelerated mutation, we can peer into the future of MRSA evolution here on Earth. Lead researcher Dr. Anita Goel, CEO of the biotechnology company Nanobiosym, described the hoped-for payoff of this work in an interview with space.com. “Microgravity may accelerate the rate of bacterial mutations,” she said. “If we can predict future mutations before they happen, we can build better drugs [to fight them].”

“Microgravity may accelerate the rate of bacterial mutations”

Why the focus on MRSA? MRSA infections typically result in a mild skin infection, but they can cause more serious infections of the skin, surgical sites, blood, urine, or lungs. They thrive in hospitals because they are hard to kill and spread easily in already-sick patients. A 2013 study estimated that 1-in-12 hospital patients in Canada has MRSA or another superbug. This is actually a decrease from previous years, but overall MRSA infections are becoming more common in Canada and internationally.

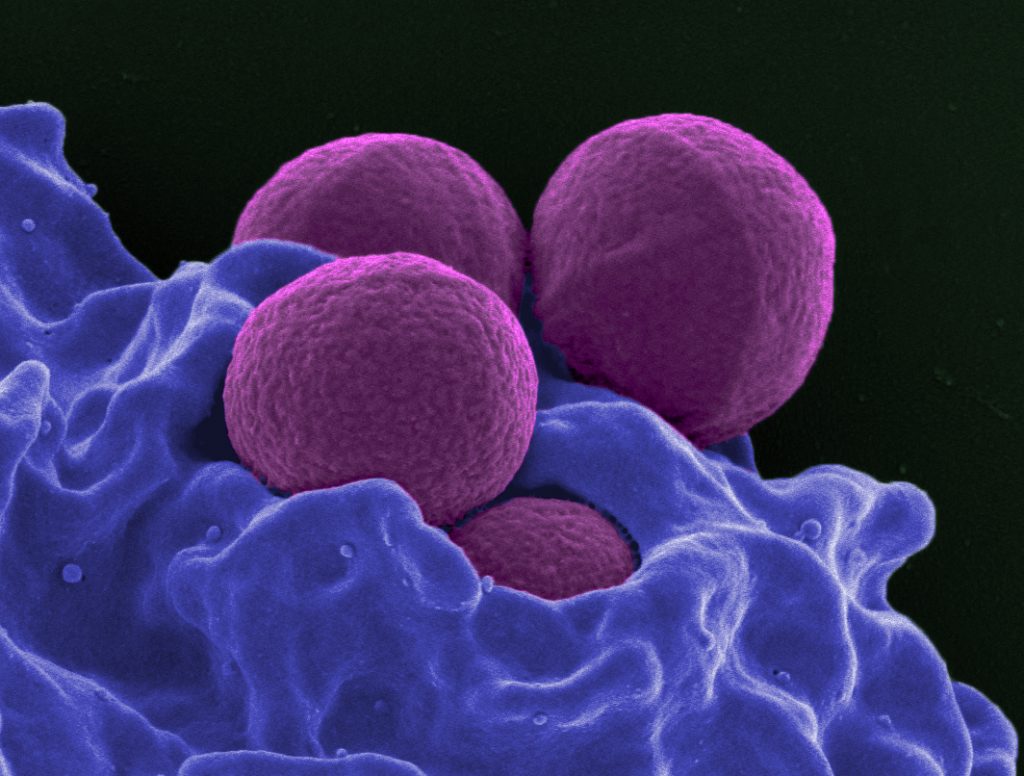

Scanning electron micrograph of a human neutrophil ingesting MRSA (purple).

Credit: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health.

MRSA and other drug-resistant superbugs are a huge threat to global public health because they have developed immunity to antibiotics – in some cases even the strongest antibiotics we have. As resistant microbes spread, our defences against them are reaching their limits. Global public health leaders have warned of a post-antibiotic era in which we’ll need to rely on other medical technologies to treat currently preventable diseases. Microgravity research is one way to prepare for this possibility.

Of course, space isn’t the only place researchers are looking in their efforts to prevent and treat MRSA infections. They are also exploring silver ions, CRISPR gene splicing technology, nanotech, medical marijuana, extracts from the Brazilian pepper tree, and even a sea sponge.

But space medicine holds unique promise in bacterial research and beyond. And the Canadian Space Agency is jumping on the space medicine bandwagon too – with studies exploring how gravity affects bone density and circulation, and the impacts of radiation on astronauts. Here on Earth, this knowledge could improve rehabilitation for patients who spend long periods of time in hospital beds from prolonged illness.

Projects like these highlight how space is the next frontier of medical research, and provide us with bold new opportunities to improve human life.

*Header Image: NASA/Crew of STS-132