By Mary Anne Schoenhardt, Science in Society editor

What comes to mind when you think of the term Anthropocene? A dystopian novel? A hazy city filled with smog? Or do you think of the Holocene or Pleistocene epochs, and exhibits on evolution at the museum?

While it may sound like something out of pop culture, Anthropocene is a term that has been proposed to describe the current epoch, which is characterized by widespread changes to our natural environment that are driven by human activities.

The term Anthropocene was first used by freshwater biologist Eugene Stormer in the late 20th century and later popularized by atmospheric chemist and Nobel Laureate Paul Crutzen. Since then, it has appeared numerous times in the scientific literature and there is even a peer reviewed journal with the name. While scholars in many disciplines refer to the current period as the Anthropocene, it has not officially been declared a geologic epoch by the International Commission on Stratigraphy.

What is an epoch?

An epoch is one of the shortest divisions of geologic time and is identified in the rock stratigraphy by characteristic sediment deposits. The types of sediments that are deposited are a direct consequence of the atmospheric, climatic, and geographic conditions during that time. The order the sediments are deposited in and their chemical composition are like a fingerprint of each epoch.

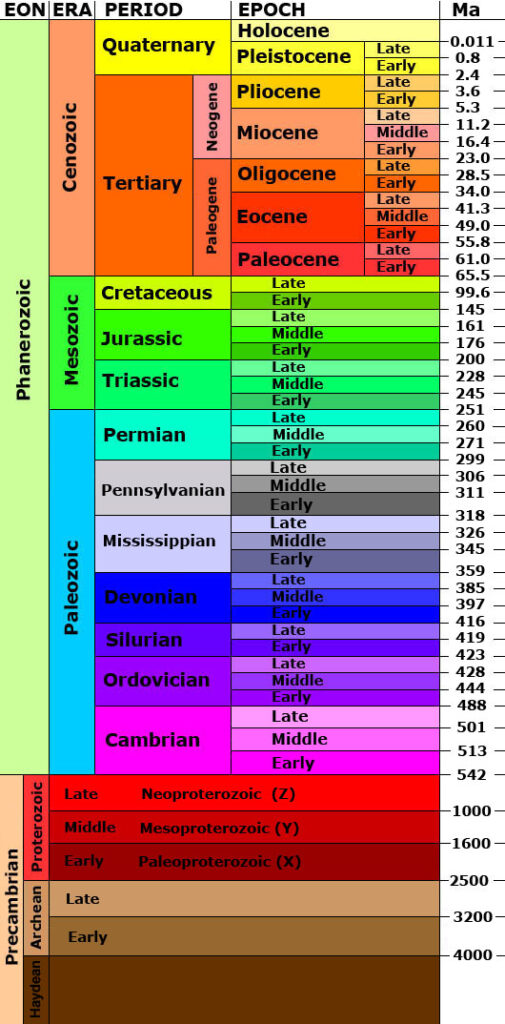

Geologic time is divided into eons, eras, periods, and epochs. We are currently in the Holocene Epoch (top right). Image: USGS, Public Domain.

Stratigraphy is a branch of geology that studies the characteristics and relative order of sediment layers. It is used to better understand our earth’s history, including defining the duration of epochs.

For a new epoch to be declared, a globally agreed upon location must be identified that exemplifies the lowest, or earliest, point of a given stratigraphic layer. This location is referred to as a Golden Spike. The single layer of iridium between two Moroccan clays that was left by the asteroid that led to the extinction of dinosaurs and marked the start of the Paleocene is such a marker. To be declared a new epoch, the Anthropocene would not only have to leave behind unique sediment that will be perceivable millions of years from now, but a Golden Spike must be identified.

Sediment cores allow stratigraphers to study deposited sediment. In this core from Alaska, grey layers of volcanic ash can be identified amongst the top layers of the sediment core. Photo: Oregon State University, CC BY-SA 2.0.

Identifying the Anthropocene

The Anthropocene Working Group, a body within the International Commission on Stratigraphy, is responsible for trying to determine what the epoch defining sediment looks like and identifying a Golden Spike location. Just last year, almost 15 years after the formation of the Working Group, a potential location for the Golden Spike of the Anthropocene was discovered.

Twelve sites across the world were proposed as the Anthropocene Golden Spike. The sites were chosen in locations where sediments were deposited but not mixed with the surrounding sediment so that the start of the Anthropocene can be accurately dated.

Crawford Lake, a small lake in southern Ontario, was nominated as the Golden Spike location because of its thick sediment bands that can be dated very precisely—to within a year. By the 1950’s, there was a significant increase in carbon particles, plutonium particles, and nitrogen isotopes in the lake’s sediments, thought to be from nearby Hamilton’s steel mills, atmospheric nuclear testing, and an increase in fertilizer use in agriculture and acid rain, respectively.

Declaring a new epoch

For the Anthropocene to be declared a new epoch, the proposal submitted by the Anthropocene working group must be voted on by three higher bodies. The first of these three bodies is the Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy who state that for the Anthropocene to be declared a new epoch, it must be both scientifically justified (that is, it is adequately distinct from previous epochs) and useful for the scientific community.

Are the changes in carbon, plutonium, and nitrogen concentrations found in Crawford Lake sediments distinct enough? And while they are undeniably different from previous sediment layers, will they still be perceivable in 100,000 years? Epochs span time scales of hundreds of thousands of years, and it has only been 70 years since the proposed start date of the Anthropocene. And while the term Anthropocene has already proven useful to global change studies, does its declaration as a formal epoch of geologic time increase this utility?

While the validity of the vote has since been challenged, recent results from the Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy suggest that no, the 1952 sediment with carbon, plutonium, and nitrogen from Crawford Lake is not an appropriate signature for the Anthropocene. Members of the Subcommission who voted against the proposal argue that humans have been altering the planet for much longer than 70 years—they cite the increased carbon emissions starting during the industrial revolution and the advent of farming millennia earlier. They also suggest that anthropogenic impacts on the planet are too global to be represented by a single location and sedimentary signature.

A proposed alternative to declaring the Anthropocene as a new epoch has been declaring it a geologic event, much like previous mass extinctions or the oxygenation of the atmosphere two billion years ago. Events, while not part of the geologic time scale, take place over a definable period and can have significant impacts on the tectonics, climate, or biology of the planet.

Crawford Lake is a small deep lake in southern Ontario proposed as the Golden Spike location for the Anthropocene Epoch. Photo: DailyB, CC BY-NC-ND 3.0.

Implications of the Anthropocene

Whether the Anthropocene is officially declared a new epoch or not, what does it matter for those of us who aren’t stratigraphers? Francine McCarthy, a geologist from Brock University leading the work at Crawford Lake, says that “If people see that stratigraphers, a conservative bunch of geologists, are willing to put a line on the timescale and call it by the name that recognizes — that admits — the role of humans as a causal agency, then that’s mammoth.”

Will Steffen, a global leader in Earth-systems science, echoed this sentiment, saying “[It] will be another strong reminder to the general public that we are now having undeniable impacts on the environment at the scale of the planet as a whole, so much so that a new geological epoch has begun.”

While both quotes were made prior to the vote by the Subcommission on Quaternary Stratgraphy, even the discussion of a change to the geologic time scale highlights the undeniably large footprint that humans are having on our current environment. Will this footprint remain for another 100,000 years? Only time will tell.

Banner image: Thousands of years from now, what footprint will humans have left on Planet Earth? Image by Vojin Petrovic, CC BY-NC-ND 3.0.