Zahra Nasser, Chemistry editor

Most of us are tired of hearing about COVID-19. We’re tired of hearing that cases are rising, tired of not knowing when the pandemic is going to end and when life is going to get back to normal. Every time we check our phones or turn on the TV, we are bombarded with news about case counts and deaths, worldwide efforts to flatten the curve, and progress towards vaccines. But something that isn’t emphasized in these news reports is the human immune system: the recoveries and the hope.

In the midst of all this pain and suffering, many of us have forgotten the extraordinary capabilities of our own bodies. We often overlook how hard our bodies fight for us against pathogens such as viruses.

How does a virus infect you?

A virus is a small infectious agent that is unable to self-replicate and requires entry into a living cell to survive and proliferate. There are various ways viruses can enter your body, including through inhalation, consumption of food and drink, sexual contact, and insect bites. Once inside the body, they can infect cells. The type of cell a virus infects depends on whether receptors on its surface can bind to receptors on the host cell’s surface.

If the virus binds successfully with the cell, it will enter, invade the nucleus, and use the cell’s replication machinery (which transcribes DNA into RNA and translates RNA into proteins) to replicate its own genetic material and convert that into viral proteins, which synthesize the enzymes and proteins needed to form new viruses. The infected cell will eventually burst, releasing newly synthesized viruses into the body.

But as soon as a virus enters the body, the immune system begins to battle against it. In some cases, it may be able to kill the virus before it even affects the host. Other times, the body must fight off invading viruses after they have already entered cells.

A microscopic image of a virus, which, like other viruses, may be detected and destroyed by specific antibodies before reaching a target cell (Pixabay)

Fighting off a virus before it infects cells

You can be fighting off a virus even before realizing that something harmful has entered your body. Let’s say you just interacted with someone who has the flu and now the virus is in your lungs. Inside your respiratory tract (and throughout your body), there are immune cells called B-cells circulating in the bloodstream. On the surface of these B-cells are antibodies: unique Y-shaped proteins that bind to specific viruses or pathogens. The type of antibodies you have depends on your unique infection history. If you have the right antibody for the invading virus, the two will bind, like a key fitting into a lock. This binding will cause proteins to mark the virus for phagocytosis, a mechanism by which a cell engulfs and destroys a virus.

The binding of an antibody and virus also initiates self-replication of the B-cell containing that antibody, increasing the number of antibodies present in the respiratory tract. The goal: neutralize viruses before they can infect cells, thus saving you from something you had no idea you were going through!

You’re infected! Now what?

But let’s say you weren’t so fortunate, and your antibodies didn’t detect and destroy the virus before it entered your cells. Even though you might be spending a couple of days in bed, your immune system will be working round-the-clock to recognize and destroy infected cells.

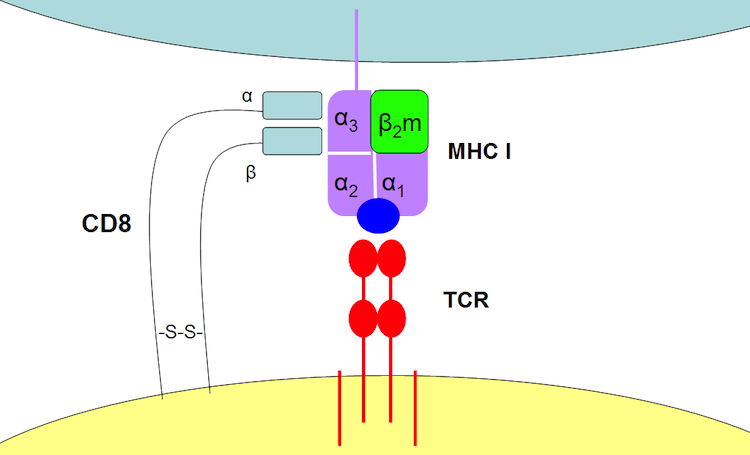

All cells contain membrane proteins called MHC class I proteins which take samples of viral proteins inside the cell and move them to the cell membrane to expose these samples to the extracellular matrix. Immune cells circulating in the bloodstream, called T-cells, contain T-cell receptors (TCRs) that detect the exposed viral proteins. Similar to antibodies, TCRs have a uniquely shaped receptor region which only binds to specific proteins. After binding, the T-cell activates and signals for a cascade of events that causes the destruction of the entire infected cell.

T-cell receptors were first discovered by James Allison in 1982, but the specific structure of the receptor wasn’t known until two years later, when it was co-discovered by Dr. Tak Mak, a Canadian researcher who currently works at Princess Margaret Cancer Center. His discovery shed light on the components of T-cells that allow them to recognize and respond to viruses. T-cell receptor binding depends on the cell’s ability to recognize both the MHC protein and the viral protein it has exposed. Mak and his team investigated how T-cells recognized both components – specifically, whether TCRs had two separate receptors or only one. They discovered that it was a single receptor capable of recognizing and binding both the MHC and viral proteins. In a 2009 interview with Legion Magazine, Mak explained that the binding specificity of TCRs is critical to their ability to “differentiate between a piece of a virus or a piece of our own cells”.

Tak and his colleagues concluded that a TCR is a single receptor (red structure) capable of recognizing and binding to both the viral protein (blue) and MHC I (purple/green). Image by Itayba at Hebrew Wikipedia is licensed under CC BY SA 3.0

Interferons are another type of immune cell that act on infected cells. They stop viruses from replicating by initiating the production of proteins that interfere with the replication process. The production of interferons is triggered when pathogen recognition receptors (PRRs), which are present in innate immune cells, interact with viral DNA or RNA. Once produced, interferons trigger the synthesis of proteins, such as Mx and PKR, which bind to viral RNA and inhibit its translation into proteins.

T-cells are one of the heroes of our immune systems, fighting against pathogens after they’ve infected our cells. 3-D illustration of T-cell by Blausen Medical, licensed under CC BY 3.0.

The heroes we don’t hear about

Keeping in mind that B-cells, T-cells, and interferons are just a few of the ways our bodies fight viruses, it’s clear that our immune systems are formidable opponents. Even though most of what we hear in the media these days is about the suffering caused by COVID-19, we can take some comfort in the multiple avenues of defence our bodies have evolved to protect us. And while they certainly aren’t infallible, and SARS-CoV-2 does pose a novel threat to our immune system, it’s worth remembering that of the 178 million COVID-19 cases reported worldwide (as of June 18, 2021), 162 million are considered recovered.

~30~

Your blog is very informative.