Robert Gooding-Townsend, Science in Society co-editor

Last October, at the height of the American presidential election, the internet was talking about nothing else. Well, almost. Amongst all the takes on Sanders and Clinton and Trump and Rubio and the future of America, one story rose to the top of The Atlantic’s website and stayed there. It was about lichens. And it was written by Ed Yong.

This was the latest in a long string of successes for Yong (pronounced “Young”). Having started his blog Not Exactly Rocket Science while working full-time for a cancer charity, he attracted a large audience, pitched to major publications, and won prestigious awards. More recently, he has transitioned into a full-time staff writer at The Atlantic and is the author of the bestselling book, I Contain Multitudes, about microbiomes.

In a keynote address at the Canadian Society of Microbiology conference on June 20th in Waterloo, ON, Yong explained the craft behind his stories. Along the way, he described the superpower we all have, his frustrations with “clickbait”, how to get audiences engaged with science, and the stories we should resist telling.

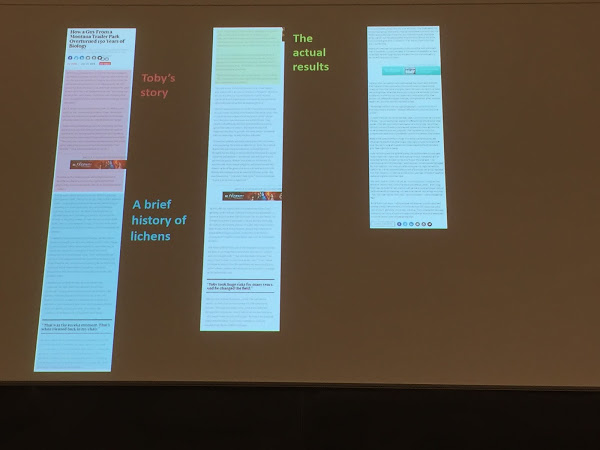

A slide from Yong’s talk, highlighting major sections of the lichen article: Toby’s story, a brief history of lichens, and finally the actual results.

As an illustration, he took apart the lichen story. The story is a bit unusual. The central finding it describes is remarkable: contrary to the classical understanding of lichens as a two-way symbiosis between an alga and a fungus, it’s a three-way symbiosis, with an alga and two fungi. But Yong didn’t reveal this key point until halfway through, abandoning the results-first approach of the traditional “inverted pyramid” reporting style.

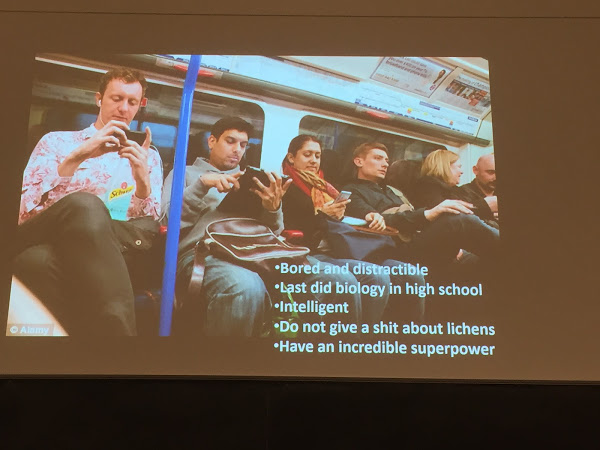

Why did he do this? As he explained, his audience – and almost any modern audience – is smart, though without much domain knowledge, and easily distracted. Most importantly, they “don’t give a shit about lichens”. The first step is to get them to care.

Yong’s target audience: bored and distractible riders on the London Underground. They’re intelligent, but last did biology in high school, and “do not give a shit about lichens.” They have an incredible superpower: the ability to stop reading.

This is the main challenge of science writing, and Yong had a lot to say about it. Science writing is a constant battle for attention, against readers whose superpower is that they can stop reading at any time. He cites the attitude of “nobody has to read this crap” as a mark of professionalism in science writers: inexperienced writers are often just writing for themselves, with self-indulgent monologues on how they got to a particular topic.

To get attention, there are a couple of common strategies. One is to resort to hype and exaggerate findings – but as Yong says, “When incremental advances get turned into massive groundbreaking magic bullets, you’re doing people a disservice and you’re doing science a disservice.” Another way is to talk about connections to pop culture, everyday life, or practical applications. This isn’t as objectionable, but it does imply “that people are quite narcissistic, and science is a little boring. And I don’t believe either of these are true.” Instead, Yong’s preferred technique is telling stories: one event following another, focusing on what the reader wants to hear, with plot twists and surprises along the way.

For the lichen story, Yong started by introducing Toby Spiribille, the researcher who led the work. Toby grew up poorly-educated in a Montana trailer park, in what he would now describe as “a sort of fundamentalist cult”, as far from the world of science as you can get. So how did he end up leading this research? And given all of those difficulties, why would he choose to study lichens? This backstory – getting people to care about lichens by caring about the people who study lichens – is how Yong guides the reader to the main result.

As he notes, none of this backstory is in the paper. He couldn’t do the most important part of his job without conducting interviews and finding stories – which is why it rankles him when people say science writing is just translating journal articles.

Toby’s backstory is also what motivated the headline: “How a guy from a Montana trailer park overturned 150 years of biology.” This has gotten accusations of clickbait – but as Yong says, “It’s not clickbait if it actually delivers what it promises. That’s just a headline.”

“Aside from telling stories, we need to think about stories we should resist telling.” — Ed Yong

But science journalism is about more than just enticing stories and snappy headlines. “Aside from telling stories, we need to think about stories we should resist telling.” In particular, this includes hype and overly credulous stories. For Yong, this is the distinction between science communication, which often takes a “yay science” attitude, and science journalism, which is often quite critical. Some of his calls for skepticism have covered replicability in genetics research, the lack of evidence for brain training games, and sensationalist claims about the microbiome.

He doesn’t shy from turning this critical eye on himself. Following the lead of his colleague Adrienne LaFrance, who analyzed her reporting for gender bias, he collected the demographics of the sources who appear in his stories. When he started tracking the sex of his sources, only 25% were female. A year later, 50% of his sources were female. Collecting the data “allowed me to stop bullshitting myself that everything was fine, and gave me something to work towards.” Now he’s working on improving the racial diversity of his sources. In the meantime, he maintains deliberate diversity in the accompanying images: “It is a statement about who we get to see when we see stories about science.”

At the end of his presentation, Yong invited all the conference attendees to share their stories, whether with a journalist, writing themselves, participating in storytelling nights, or in any other way. You never know what people will take a lichen to.

Header Image: Ed Yong at the Canadian Society of Microbiologists conference in Waterloo. The background slide reads “You do not deserve attention. You earn attention.”

All photos by Erin Zimmerman for Science Borealis.

My colleague Erin Zimmerman and I would to thank the organizers of CSM 2017 for providing us with press passes for this event. We’re excited to be following up this summary of Ed’s conference presentation with an exclusive one-on-one interview about science communication and his career in it. It will appear later this month on the Borealis Blog.

One thought on “Turning science into stories: The craft of Ed Yong”

Comments are closed.