By Josh Silberg, Policy and Politics Editor

Be prepared. Between scouts and the Lion King, this motto was heavily emphasized during my younger years. And yet, “make earthquake emergency kit” has remained unchecked on my to-do list for months. Since I live on a major fault line, my former scout leader – my dad – would not be pleased. My own unpreparedness aside, who do we rely on when a natural disaster hits in Canada? Who will be there to help?

In many ways, Canada’s approach to emergency management mirrors the United States’ system. In both countries, emergency management is broken down into prevention and mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery. And most emergencies are handled by those closest to home. Local municipalities or districts are the ones with primary responsibility for emergency management.

“Depending on the size of the community, emergency management could be covered by anywhere from multiple full-time staff to one part-time employee to the local fire marshal. And each local authority should have enough resources to handle local issues,” says Dorit Mason, Director of North Shore Emergency Management Office (NSEMO), which coordinates emergency management for the three municipalities on the north shore of Vancouver.

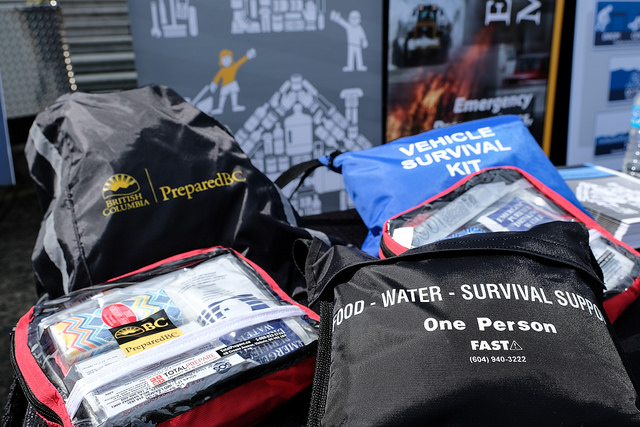

Emergency survival kits are shown here at the “Shake Zone”, an earthquake simulator that provides a sense of the impact a high-magnitude earthquake could have on coastal communities. Photo: Province of BC, CC by 2.0.

If an emergency is serious enough, Canadian municipalities can declare a “state of local emergency”. Critically, even without such a formal declaration, relief funds are still available. Canadian authorities only need to declare a state of emergency when extra powers are absolutely necessary – for instance, to shut down roads, to conscript people, or to enter private property – not to get financial reimbursement.

And this is where the two neighbouring countries’ emergency management policies begin to diverge. In the US, the state governor must declare a state of emergency and put in an official request to the President before federal authorities can get involved and provide relief funds.

Removing this requirement depoliticizes disaster relief. Since many smaller emergencies do not require these extra powers, discretion can be used to minimize the infringements on people’s rights. Plus, politicians aren’t inclined to unnecessarily declare states of emergency merely to access relief funds.

“We don’t declare a provincial state of emergency very often,” says Heather Lyle, Executive Director of Plans and Mitigation with Emergency Management British Columbia.

British Columbia is the only province or territory with a dedicated provincial minister whose mandate is to coordinate emergency management.

“Local authorities tend to declare local states of emergency more often than the province ever needs to, but that’s to be expected. Every local authority has different capabilities, capacity, and resources. It might take quite a significant event in the City of Vancouver to declare a state of local emergency versus [smaller communities] who may find themselves requiring additional authority and support, so need to declare a state of local emergency for a much smaller scale event,” says Lyle.

While each province and territory has its own legislation and emergency management authority, there are many similarities across Canadian jurisdications. Above all, these provincial and territorial agencies play an integral role before, during, and after an emergency.

“When the province steps in, we don’t take over. We are there to listen to what their needs are, to provide them, and anticipate what kind of support [local authorities] might need. The province’s job is to do that next level of activation, to maintain monitoring with the local authorities, to expedite the movement of resources, and bring it in to support them,” says Lyle.

“Governments can only do so much. The personal responsibility is to be prepared for 72 hours, at minimum…”

Public Safety Canada, created in December 2003, is the federal authority in charge of emergency management in Canada. The federal government plays a considerable financial role by providing disaster relief funds. Public Safety Canada covers almost all approved emergency response costs and most of the costs of restoring infrastructure to pre-emergency conditions.

“Say we have more than one region impacted, or it’s a very significant regional event that we’re dealing with, the fed[eral government]’s job is to activate and to anticipate what federal resources, financial aid, could be brought in to support the province, so that, in turn, the province can coordinate support to the local authorities,” says Lyle.

There remains room for improvement. In 2009, the Office of the Auditor General conducted an audit of federal emergency management in Canada and found that the department had not yet clearly defined its leadership role. In addition, in 2013, a separate federal audit of emergency management on First Nations reserves found that more federal funding and better coordination were sorely needed.

“All three levels of government – the local, provincial, and federal – we work collaboratively before disaster strikes..”

It’s not just at the federal level that we can improve in Canada. While we do have a federal Minister of Public Safety, British Columbia is the only province or territory with a dedicated provincial minister whose mandate is to coordinate emergency management. Having political figures devoted to emergency management is important to help guide emergency management in the provinces.

But even though improvements could be made, emergency management coordination in Canada seems to be on the right path.

“We have a great working relationship with the provincial agencies. From our [local] perspective, this system works really well,” says Mason.

“All three levels of government – the local, provincial, and federal – we work collaboratively before disaster strikes,” adds Lyle.

Regardless of the nuances of Canada’s emergency management bureaucracy, in the end it is up to us to be ready when emergencies occur.

“Governments can only do so much. The personal responsibility is to be prepared for 72 hours, at minimum,” says Mason.

Duly noted. Now, I need to appease my scout leader by finally checking a box off my to-do list.

Header image: North Shore Search and Rescue practice helicopter lift. Credit: Curtis Jones, Simon Fraser University CC by 2.0.