Kira Hoffman, General Sciences co-editor

In December 2014, residents of Jordan River received some unwelcome news. The 103-year-old Jordan River Dam, located 7 km upstream of this tiny seaside community on southwestern Vancouver Island, had been deemed unlikely to withstand a major earthquake.

Six years earlier, BC Hydro had commissioned a peer-reviewed study on the seismic soundness of its 79 dams in British Columbia. The Jordan River Dam was found to be the most likely of these to fail. It was believed that if this happened, the sudden release of water stored in the reservoir behind the dam would produce catastrophic flooding and destroy the community.

As a result, residents were forced to sell their homes at market price to BC Hydro. The campground at the river mouth was closed, and residents received hand-delivered letters containing the promise that BC Hydro would provide compensation for their losses. With little notice and almost no public consultation, the decision had been made.

On the other side of the Strait of Juan de Fuca, less than 50 km as the crow flies south, the Elwha Dam in Washington has a similar story, but a very different ending. Like the Jordan River Dam, it was built over a hundred years ago in an era of mega hydroelectric construction projects, and was heralded as a progressive structural and economic feat.

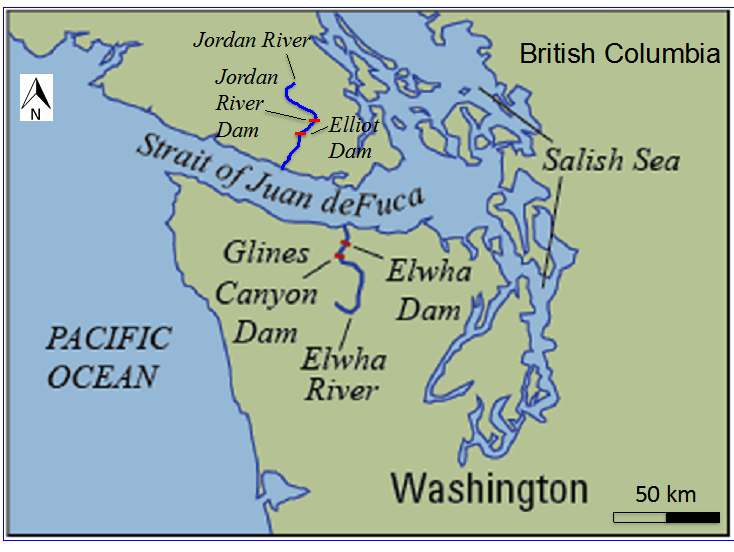

Both the Jordan and Elwha rivers were blocked by two major dams, built to supply power for local communities (Victoria in B.C. and Port Angeles in WA) and support major industries such as logging and milling. The Jordan River Dam (upper Jordan River) and the Glines Canyon Dam (upper Elwha River) were once the tallest dams in their respective nations.

The locations of the two Jordan River and two Elwha River dams. Map adapted from the USGS.

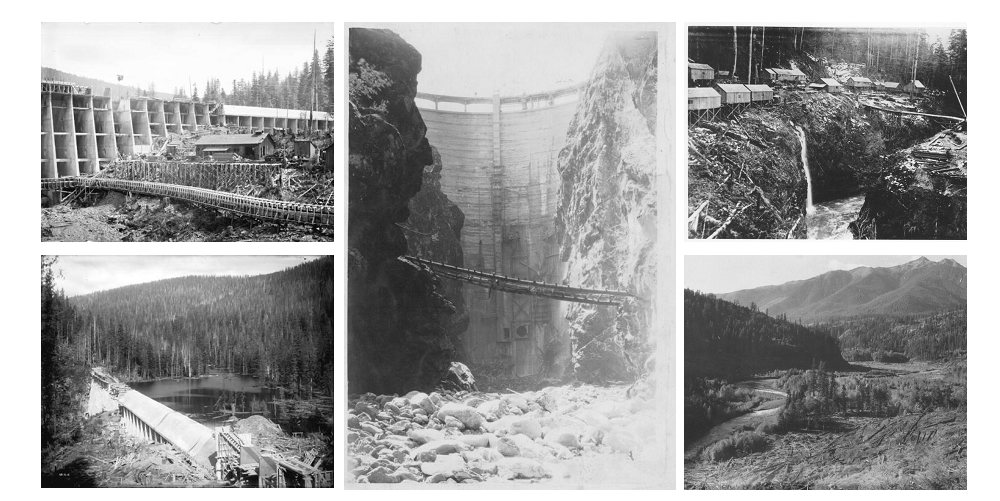

At the beginning of the 20th century, rivers were known to possess massive amounts of energy that could be harnessed for economic gain. Little consideration, however, was given to the 10 different runs of anadromous (ocean-going) fish that relied on the Jordan and Elwha rivers to spawn. The dams on the Jordan and Elwha rivers were constructed without fish ladders and completely obstructed salmon migration. Historically, the Elwha River had annual runs of some 300,000 salmon (ten salmon species). The Jordan River had runs of about 10,000 salmon (potentially six salmon species), but it is unclear whether these estimates were established prior to dam construction or before copper and gold mine tailings heavily contaminated the river beginning in 1919.

The Jordan River Dam under construction in 1910 (upper and lower left). The Glines Canyon Dam (upper Elwha) after its completion in 1927 (middle). The Elwha Dam construction camp in 1910 (upper right). The Elwha River prior to flooding the reservoir in 1913 (lower right). Images courtesy of Clallam County Historical Society and the Royal BC Museum.

By the 1970s, the dams had outlived the industries they once supported, and required millions of dollars in upgrades to maintain safety. This is where the tale of the two rivers diverges.

The Jordan River dams were upgraded in the 1970s, and again in the early 1990s, at a cost of millions of dollars. Today, approximately 80% of Vancouver Island’s electricity is delivered through underwater cables from the B.C. mainland. Although the Jordan River dams are still operational, they only supply power to the city of Victoria during times of peak power usage (about 10% of the city’s needs).

In 2014, the Jordan River dams again required hundreds of millions of dollars in seismic upgrades, and BC Hydro evaluated three potential courses of action. The company decided that decommissioning and removing the dams would be too expensive, and that lowering the level of the reservoir would eliminate flood risk but entail the loss of a backup power source for the city of Victoria. To BC Hydro, the choice was clear: the solution was to keep the dams in place, maintain the level of the reservoir, and buy the nine waterfront homes and the $3 million campground to clear the danger zone. (As salmon had not been seen spawning in the river since the 1950s, fish were not considered in the assessment.)

…how do we deal with derelict dams that restrict the free flow of rivers and cause significant ecological damage?

On the American side of the Strait, the raison d’etre of the Elwha dams had been rethought. In the 1980s, perspectives on rivers and environmental policy were beginning to shift and governmental bodies, including the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe, the Department of Fish and Wildlife, and the US Geological Survey, and several non-governmental organizations concluded that the Elwha dams, which had devastated the Elwha’s native fish populations, were obsolete and should be removed.

In 1994, the Elwha Act was passed by Congress, which required that both Elwha dams be decommissioned and removed to restore critical fish habitat. After 20 years of planning, dam removal began in 2011, an event documented in the film Damnation. Click here to watch a time lapse of the Elwha Dam removal.

The total cost of the Elwha River restoration, including the purchase of the two dams, construction of two water treatment plants, the construction of flood protection, and a fish hatchery, was US $327 million. The estimated cost of removing the Jordan River dams was CAN $100–200 million.

The Glines Canyon Dam (upper Elwha) pictured in 2014 after its removal. Photo by James Wengler.

The planned demolition that breached the Elwha Dam in the summer of 2011 could be heard for miles. Three years later, the Glines Canyon dam on the upper Elwha was removed. Today, the Elwha River is still carving a new path to the Strait of Juan de Fuca. The removal of the dams has come with some hiccups – including widespread flooding in the fall and winter of 2015/16, which damaged several park facilities that had been built in the historic river channel.

River restoration efforts are ongoing, but early scientific studies are clear – almost overnight, access to critical salmon habitat was restored. One week after the blast, salmon were seen spawning above the Elwha Dam site for the first time in over a century.

Coho salmon are blocked from migrating past the lower Elwha Dam. Image from the Seattle Times.

Back on the Canadian side, as of October 2016, BC Hydro had successfully purchased the public campground and eight of the nine homes in the village of Jordan River; one resident was refusing to move.

Meanwhile, salmon are still unable to move into their historic spawning grounds and water levels in the river are often too low to maintain viable habitat. Although the Jordan River was not as famed as the Elwha for its salmon runs, it was a valued salmon river. Over the last decade, salmon stocks in many B.C. rivers have been considered below normal. The depletion of salmon has been attributed to several causes, including habitat loss, and removing deteriorating dams and renewing salmon habitat would assist long-term salmon recovery.

Although keeping the status quo on the Jordan River may be the simplest and cheapest short-term solution, it doesn’t answer one of the many difficult questions that B.C. and Canada are facing – how do we deal with derelict dams that restrict the free flow of rivers and cause significant ecological damage? It’s not just an economic question, it’s also an environmental one. In the longer term, who can put a price on wild salmon re-populating their ancestral homes and bringing a once-wild river back to life?

*Header photo: The Jordan River Dam (upper Jordan River) on Vancouver Island, British Columbia (BC Hydro photo).