In a Japanese ikebana flower arrangement, three stems are fixed at specific angles to represent heaven, earth, and man. Not only is it important to pay attention to the lines that those, or any additional stems, form, it’s also important to respect the spaces between those lines. We can recognize and value the spaces between things by exercising a different perspective, which is exactly what software engineer and creative coder Owen Fernley has accomplished with his new work, Between the Sand.

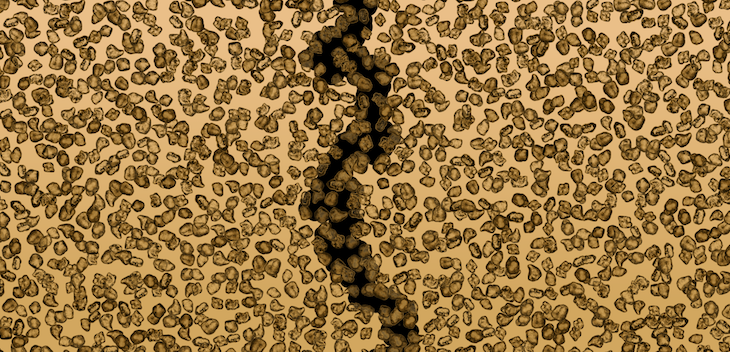

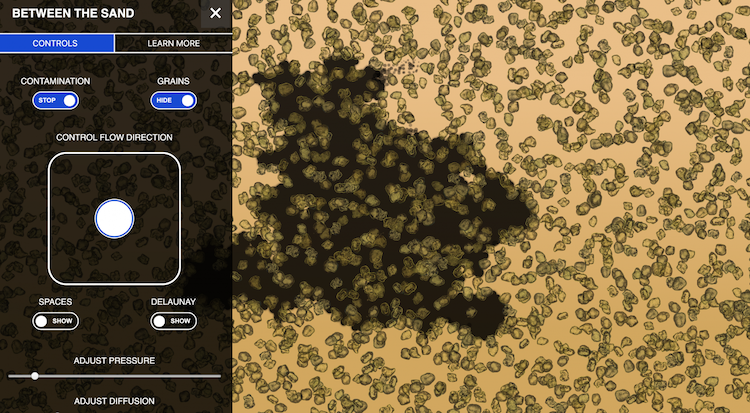

The final product of a two-week, three-phase science art residency facilitated by non-profit organization Art the Science (ATS), Between the Sand is a digital, interactive program that traces the movement of a gas as it contaminates a scattering of sand. Released online in Phase III (Online Exhibition) of the residency, users decide the origin of the gas by clicking on or tapping different areas of the screen and watch as the gas slowly engulfs it, turning a frame of luminous golden sand into an abyss of buried gold nuggets.

Program users can adjust variables to perform their own experiments and, as Fernley says, “come up with unique imagery.” For example, you can change the direction of gas flow or increase the pressure to make the gas spread faster. Fernley explains, “I wanted to enable people to play with the settings the same way I was able to play with the algorithms inside the code.” Between the Sand also has different colour schemes and a lava lamp mode, where the program is put on autopilot, and users can sit back and be mesmerized by a hypnotic dance of contamination.

The movement of gas follows the Invasion Percolation algorithm, which is known for generating outcomes that follow predetermined pathways and is used in environmental engineering research labs. At Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, one such lab provided the scientific environment for Phase I (In the Lab) of Fernley’s residency. Run by Dr. Kevin Mumford, an environmental engineer and Associate Professor in the Department of Civil Engineering, the lab works with academic and industry collaborators to study how fluids and gases move and interact in subsurface environments.

Artist Owen Fernley and several members of Dr. Kevin Mumford’s research group. (From left to right: Matan Freedman, Owen Fernley, Nick Pease, Kevin Mumford, Caroline Wisheart, and Dr. Van De Ven; Phase I). Image courtesy of Julia Krolik.

Because his lab conducts visually pleasing experiments, Mumford thought it would be well-suited for an artist residency and welcomed Fernley and his endless barrage of questions. “He immediately struck me as a curious person, and you don’t have to talk to him for very long to appreciate that he has a diverse set of experiences and interests that allow him to adopt or appreciate different perspectives,” Mumford says.

With a background in research geophysics, Fernley already had some technical knowledge before entering Mumford’s lab and knew they “would have some interesting physics to model.” Drawn towards the “creative exploration of algorithms” as he observed the research group’s projects and experiments, Fernley found his code’s complement in the work of Dr. Cole Van De Ven, who recently became a Postdoctoral Fellow in the Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences at the University of British Columbia.

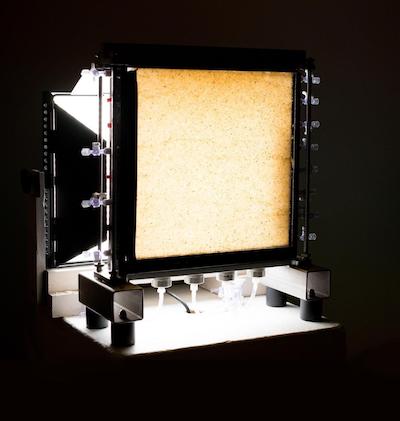

Sand flow cell used in Dr. Van De Ven’s experiments (Phase I). Image courtesy of Liam Rémillard and Julia Krolik.

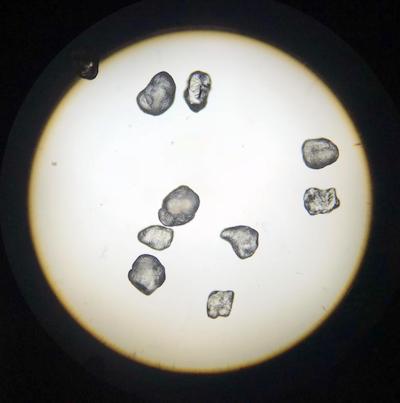

Van De Ven studies the movement and fate of geo-environmental greenhouse gases in the critical zone. His experiments use an apparatus called a light transmission cell, which he designed and modified in collaboration Mumford. The cell consists of an illuminated square frame packing water and sand between two transparent plates, through which the movement of an injected gas can be observed – a window into what happens underground.

Attempting to replicate Van De Ven’s work with the light transmission cell in code, Fernley had to see things from a different angle, surprising the research group by recognizing the spaces between the grains of sand. Early in the development of Between the Sand, “the grid looked more like a bad computer graphic than an intricate scientific experiment,” says Fernley. “However, each time I updated the positions [of sand], I started to notice the spaces forming patterns, like the patterns you see in the spaces between words on a page. I was focussed on the grains, but now I saw that the project could be about exploring the spaces between.”

Despite the digital nature of Between the Sand, Fernley’s use of microscopic images of grains of sand elicited a phantom sensation of sand on my fingers, and as I watched the gaseous contamination invade my screen, I was taken back to the beach where I once emerged from the ocean with oil slicks on my body. It’s easy to see pollution in bodies of water or air, but we’re not so privy to what contaminants do underground.

“The sustainable management of our water resources, including groundwater, is essential,” Mumford says.

“One of the many great features of Between the Sand is that it creates a visual representation of some forms of contaminant movement in groundwater, and therefore helps people to visualize what is going on below their feet when things like gasoline, industrial products, or natural gas are unintentionally released,” says Van De Ven.

As a product of art and science, Between the Sand holds value for science communication, perhaps as a teaching tool.

Left: Owen Fernley’s Between the Sand installed at the Modern Fuel Artist-Run Centre (Phase II), February 2019. Right: Viewers interacting with Between the Sand at the Modern Fuel Artist-Run Centre (Phase II), February 2019. Images courtesy of Liam Rémillard and Garrett Elliott.

In Phase II (Local Event) of the residency, a version of Between the Sand was launched at Modern Fuel, an artist-run centre at the Tett Centre for Creativity and Learning. Between the Sand was projected on a wall and visitors engaged with the virtual work by physically pouring water down a well. A sensor in the well then triggered the spread of gas in the projection. As a companion to the work, the light transmission cell was installed on a plinth next to it, “literally putting art and science side-by-side,” as Mumford says. The artist and scientists, along with ATS Program Evaluation Officer Catherine Lau, were also assembled for a panel discussion moderated by Julia Krolik, ATS Founder and Executive Officer.

For all parties involved, Between the Sand is the start of something beyond the original scope of their work and has expanded their perspective of the relationship between science and art. It’s a primer for more STEM-inspired art, cross-disciplinary collaboration and appreciation, and awareness of hidden processes. “In the end, I am hoping the work is relaxing and visually interesting,” says Fernley, “but also demonstrates how the contamination spread [underground] is unique, and unlike the more familiar contamination effects we see in the open air, or underwater.”

Looking forward, Fernley wonders what an algorithm might sound like, and given his talent in experimental music, we just might hear it someday.

~

For more information on Between the Sand or the residency, please visit Art the Science.

How can I become a member of the site?

Same Problem Here Akbar,

Go to the Login menu on the top right, and click on register in the above left..