By Michelle Lavery, General Science Editor

Here at Science Borealis, we have no qualms about getting creative.

Science communication is all about finding new and innovative ways of getting complex information to a wide and varied audience. We’re all storytellers; we’ve got poets (Phish Doc) and artists (Raymond’s Brain and CommNatural, to name a couple) and even a couple Multimedia Subject editors who are in charge of it all! But when it comes to science itself, why do so many people hesitate to paint scientists with the same brush as creatives?

“Science does not know its debt to imagination.” – Ralph Waldo Emerson

I was recently treated to a stellar talk by the Phish Doc herself, Dr. Natalie Sopinka (@phishdoc), during a science communication session at this year’s Canadian Conference for Fisheries Research (you can find a summary of the whole session here). She defended the role of creativity in the scientific process and reminded us that many of the greatest scientists also dabbled in or were overwhelmingly successful in their artistic pursuits (Albert Einstein and Leonardo da Vinci come to mind).

When it comes down to it, creating art and doing science aren’t all that different.

Both start with an idea or hypothesis followed by planning, which may vary in intensity depending on the artist or the depth of the research.

Next comes the execution – the act of splashing paint on a canvas or pipetting DNA into a gel. This is the commitment phase. Once done, the action can’t be taken back.

When we’re finished, no matter who we are – scientist or artist – we examine and re-examine our work. Has it succeeded at addressing our research question? Is there enough yellow in the corner? Do I have enough samples? Does the light strike the subject’s face appropriately?

When we’ve come close enough to satisfaction, we timidly show our friends, family, supervisors, or colleagues. Finally, if they approve, we start to show it off. We submit our work to journals or hang our canvases in galleries for critique by our peers.

There seems to be a slowly growing pool of scientists and science bloggers who have started to talk about their creative process.

Aadita Chaudhury (@ThylacineReport) overcame writer’s block; Stephen Heard (@StephenBHeard) brought beauty back to scientific writing and discovered the natural history of his chutney; Alex Bond (@thelabandfield) found narratives to teach his students; and – you guessed it – Natalie Sopinka reinvigorated her research.

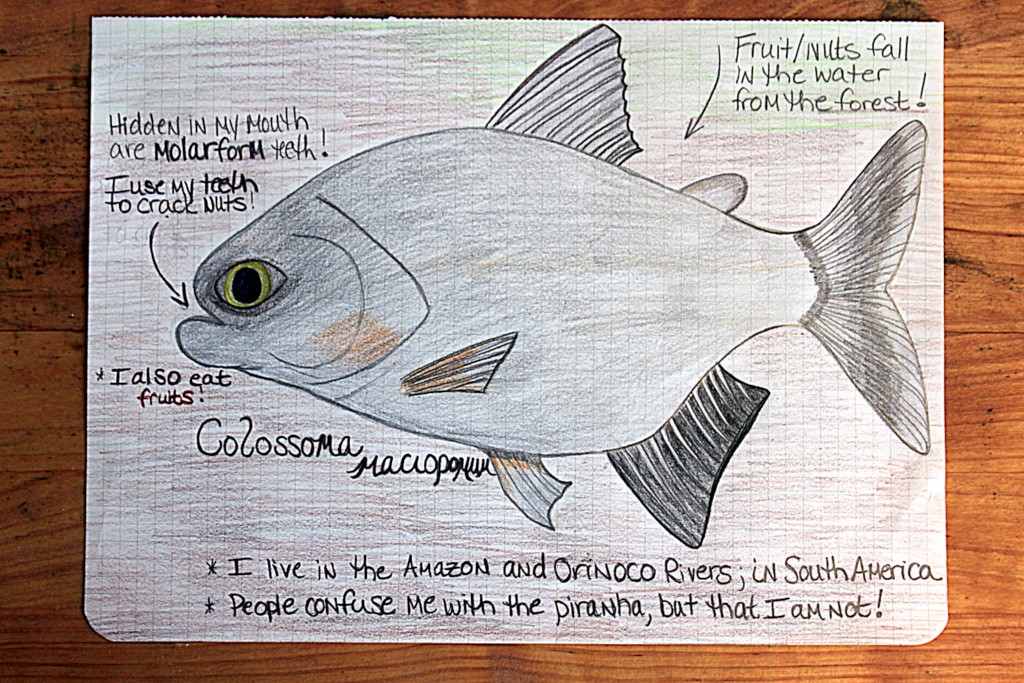

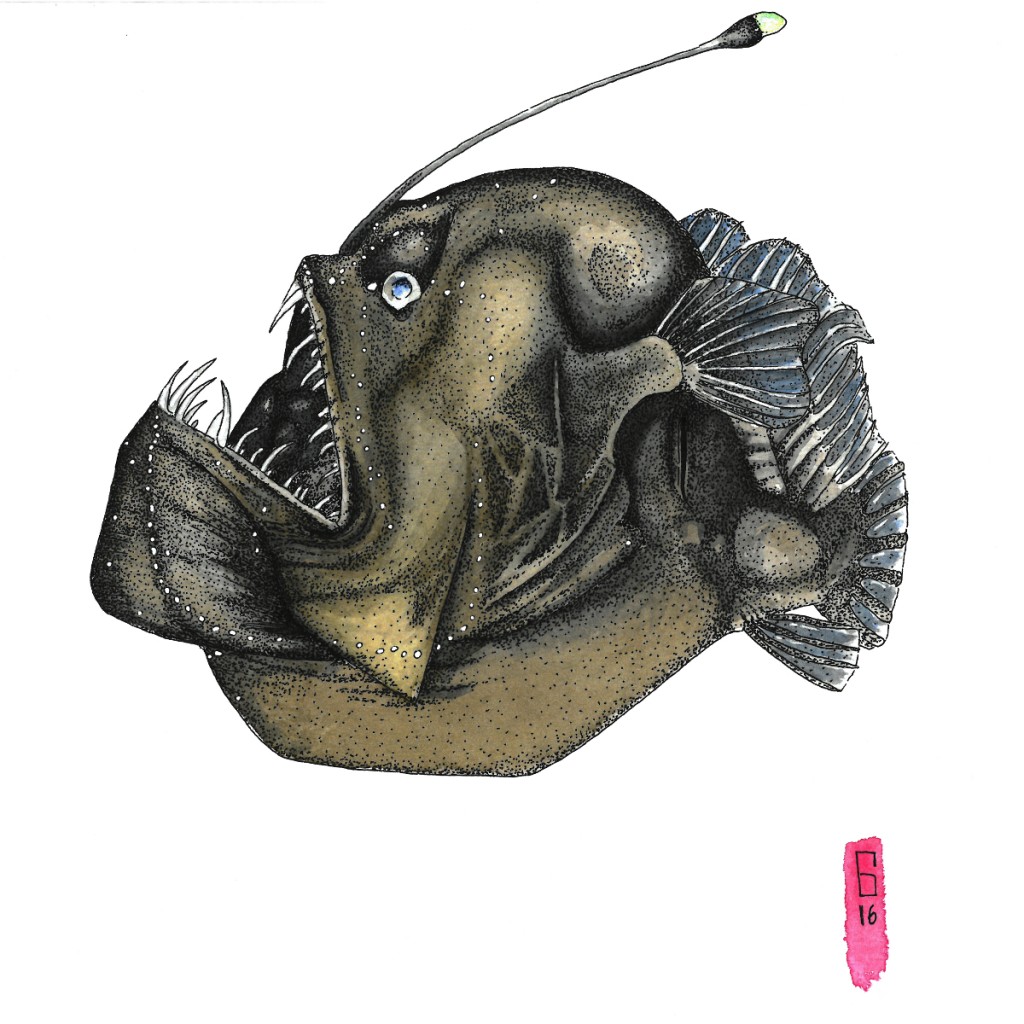

“Colossoma macropomum”, Steph Januchowski-Hartley (PhD), Université Paul Sabatier, @connectedwaters

Lately, I’ve joined these scientific creatives. I’ve been stuck on a chapter of my thesis for longer than I’d care to admit and I’m finally cracking. Following Natalie’s advice, I picked up a copy of Twyla Tharp’s The Creative Habit. After only three chapters, I recommend it as required reading for any burgeoning scientists or science writers (or humans, in general).

Tharp argues that creativity and inspiration are the products of habit without fear rather than untamed lightning strikes.

She says that with habitual practice we can train ourselves to be more creative. I can now see where Natalie was coming from when, in her talk, she advocated for indulging in our creative urges. She expanded on Tharp’s idea and hypothesized that training our creativity outside our disciplines can make our scientific ideas better and more frequent.

So the next time you’re stuck in a scientific rut, don’t be shy about the potentially unorthodox ways in which you find your inspiration. Especially given what we know about effective science communication and storytelling.

“The future for scientists is in recognizing the potential for stories… to serve their research goals. The biggest perk is that people actually remember information conveyed in a story format. It’s more intuitive than a graph, and the emotional response we have as listeners (or viewers) means the message sticks with us far longer.” – Vanessa Minke-Martin, Canadian Science Publishing Blog

Currently, my most productive days as a scientist start with ten minutes of intense, arm-flailing interpretive dance, even during fieldwork. I’m not ashamed. In fact, I’m going to be dancing more often.

*All images used with permission.

2 thoughts on “Experimenting with Creativity”

Comments are closed.